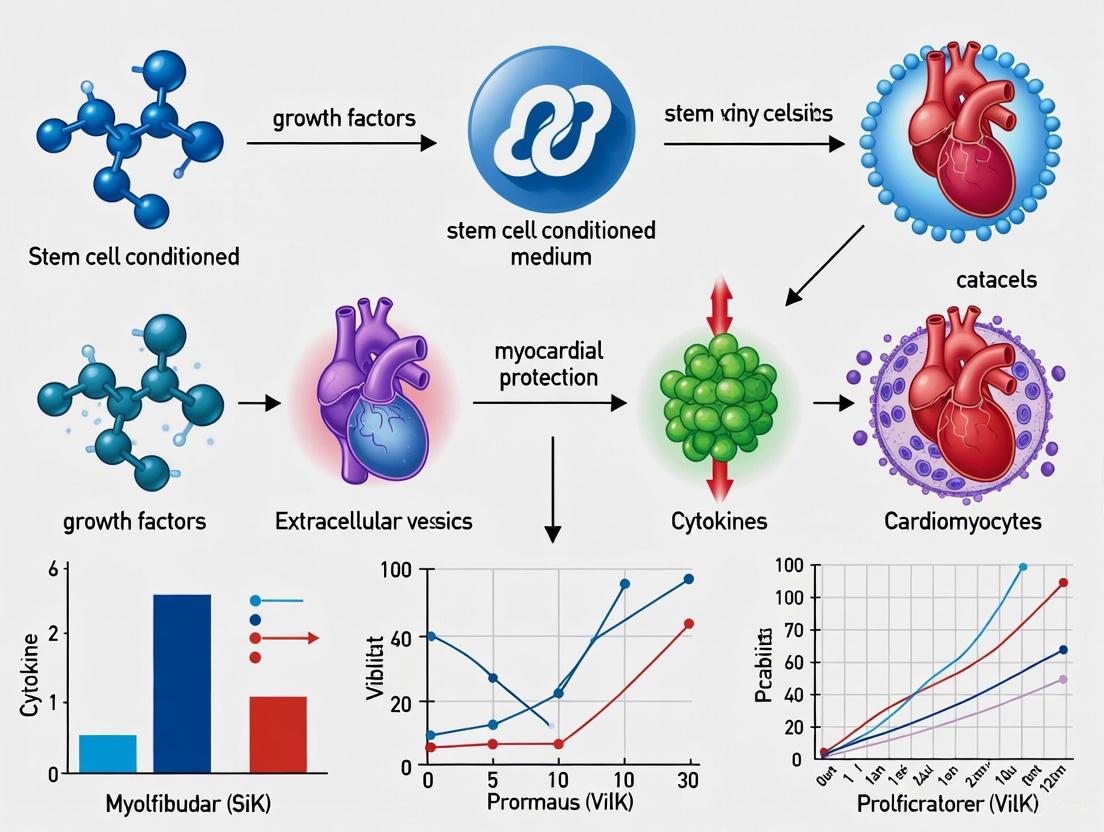

Stem Cell Conditioned Medium and Extracellular Vesicles: The Next Frontier in Myocardial Protection and Repair

This article synthesizes current research on stem cell-conditioned medium (CM) as a novel cell-free therapy for myocardial protection.

Stem Cell Conditioned Medium and Extracellular Vesicles: The Next Frontier in Myocardial Protection and Repair

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on stem cell-conditioned medium (CM) as a novel cell-free therapy for myocardial protection. It explores the foundational science behind CM's cardioprotective effects, primarily mediated through paracrine factors and extracellular vesicles (EVs). We detail methodological approaches for CM production and application, address key challenges in the field such as standardization and scalability, and provide a comparative analysis of CM from different mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) sources. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review highlights the significant potential of CM to overcome the limitations of direct cell transplantation, offering promising strategies for reducing infarct size, inhibiting apoptosis and fibrosis, and improving cardiac function after ischemic injury.

The Science of Secretomes: Unraveling the Paracrine Mechanisms of Cardiac Repair

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) consistently ranks as the leading cause of death worldwide, with heart failure due to ischemic myocardial infarction (MI) being a primary contributor to high CVD-associated mortality [1] [2]. Despite substantial healthcare expenditures (approximately US$43 billion in 2020 in the USA alone), the post-diagnosis 5-year survival rate for heart failure remains merely 50% [1] [2]. Current pharmacological therapies and mechanical devices primarily manage symptoms and slow disease progression but fail to address a fundamental pathological driver: the massive loss of cardiomyocytes (CMs) following MI [1] [3] [2]. The adult human heart contains about 3.2 billion CMs with an annual turnover rate of less than 1%, yet a single acute MI event can cause the death of approximately 1 billion CMs [1] [2]. This staggering cell loss creates a regenerative deficit that current treatments cannot reverse, making heart transplantation the only definitive cure for end-stage heart failure, with its associated limitations of cost, donor availability, and need for lifelong immunosuppression [1] [2].

The recognition of this fundamental therapeutic gap has driven the exploration of regenerative approaches over the past two decades. Initial enthusiasm focused on cell-based therapies using various stem cell types to directly replace lost cardiomyocytes and vasculature [1] [3] [4]. However, consistent challenges including poor cell survival, limited engraftment, arrythmogenesis, and modest functional benefits have prompted a strategic reevaluation [1] [3]. This has catalyzed a paradigm shift toward cell-free therapies that harness the paracrine secretions of therapeutic cells, particularly stem cell-derived conditioned media and extracellular vesicles, to stimulate endogenous repair mechanisms without the risks of whole-cell transplantation [1] [3] [5]. This review comprehensively examines this scientific evolution, focusing on the therapeutic potential of stem cell conditioned medium for myocardial protection and regeneration.

The Limitations of Cell-Based Cardiac Regeneration

Historical Context and Clinical Outcomes

Cell therapy for cardiac repair emerged from the compelling premise that introducing exogenous cells could directly repopulate infarcted myocardium with functional cardiomyocytes and vasculature [4]. First-generation clinical trials investigated diverse cell sources including skeletal myoblasts, endothelial cells, cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs), cardiosphere-derived cells (CDCs), and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [1] [2]. Human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), distinguished for their proangiogenic, anti-inflammatory, and cardiogenic-differentiation potential, have been extensively investigated for cardiac repair [1] [2]. Some MSC-based clinical trials (POSEIDON, PROMETHEUS) demonstrated improved cardiac functionality without arrythmia [1] [2]. The advent of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hPSC-CMs) further revolutionized the landscape, offering a theoretically unlimited source of cardiomyocytes for transplantation [1] [2].

Despite promising preclinical results and initial clinical enthusiasm, meta-analyses of clinical trials reveal that cell-based therapies typically provide only marginal improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 2-5% compared to placebo [3]. Moreover, complications including cardiac arrythmias and potential graft rejections continue to present significant clinical challenges [1] [2]. The transplantation of hPSC-CMs in both murine models and human patients often leads to arrythmias and poor in vivo retention [1] [2]. These limitations fundamentally redirected scientific attention toward understanding the mechanisms underlying the observed benefits and exploring alternative therapeutic strategies.

Fundamental Challenges of Cell Therapy

Several intrinsic challenges have hampered the clinical translation of cell-based cardiac regeneration:

- Poor Cell Survival and Retention: The ischemic, inflammatory myocardial environment post-MI is profoundly hostile to transplanted cells. Quantitative studies indicate that only approximately 5% of transplanted cells remain in the heart after 2 hours, declining to a mere 1% after 20 hours [3]. This catastrophic cell loss severely limits potential direct regenerative benefits.

- Immature Phenotype of Laboratory-Grown Cardiomyocytes: In vitro-differentiated hPSC-CMs structurally and functionally resemble neonatal rather than adult cardiomyocytes, exhibiting different electrophysiological properties, calcium handling, and metabolic characteristics [1] [2]. This immaturity contributes to arrhythmogenesis and poor functional integration with host myocardium.

- Tumorigenic and Immunogenic Risks: Although MSCs exhibit immunoprivileged properties, cells derived from pluripotent sources (ESCs and iPSCs) carry a risk of teratoma formation if undifferentiated pluripotent cells remain in the population [3] [4]. Allogeneic cell transplantation also raises concerns about immune rejection, necessitating immunosuppression with its associated complications.

- Logistical and Manufacturing Hurdles: Cell-based therapies face substantial challenges in scalability, quality control, storage, transportation, and timing of administration, particularly in acute MI settings where immediate treatment is crucial [5] [4].

The Paradigm Shift: Mechanisms of Cell-Free Cardiac Repair

The Paracrine Hypothesis

The consistent observation that functional benefits from cell therapy occurred despite minimal long-term engraftment led to the formulation of the paracrine hypothesis [3] [6]. This proposes that transplanted cells exert their therapeutic effects primarily through the secretion of bioactive molecules that modulate host pathways, rather than through direct differentiation and integration [3]. These secreted factors create a regenerative microenvironment that attenuates injury pathways, promotes endogenous repair mechanisms, and modulates destructive immune responses [6] [7] [5]. This conceptual breakthrough redirected therapeutic focus from the cells themselves to their secretory products, opening the door to cell-free approaches utilizing conditioned media (CM) and extracellular vesicles (EVs) [1] [3] [5].

Key Bioactive Components of Conditioned Media

Conditioned media derived from therapeutic stem cells contains a complex mixture of bioactive factors that collectively mediate cardioprotection:

- Growth Factors: Conditioned media from various stem cell sources contains identified cardioprotective growth factors including hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) [6] [7] [5]. Comparative analyses reveal that HGF is significantly more highly expressed in dental pulp-derived stem cell conditioned media (SHED-CM) compared to bone marrow or adipose-derived stem cell CM, correlating with superior anti-apoptotic activity [5].

- Extracellular Vesicles: EVs are cell-derived, nano-sized, cargo-containing biomolecules that have emerged as potent alternatives to cell-based cardiac regeneration therapy [1] [3]. These membrane-enclosed particles are broadly categorized into exosomes (50-150 nm), microvesicles (150-1000 nm), and apoptotic bodies (1000-5000 nm) based on their biogenesis pathway [1] [2]. Recent guidelines suggest referring to EVs based on size (small EVs: 50-150 nm; large EVs: >200 nm) to avoid biogenesis-associated nomenclature controversies [1] [2]. Stem cell-derived EVs (Stem-EVs) carry diverse therapeutic cargoes including microRNAs, mRNAs, long non-coding RNAs, proteins, and metabolites [1]. Fractionation studies have demonstrated that the cardioprotective activity in human MSC-conditioned medium resides in the fraction containing products >1000 kDa (100-220 nm), indicating that the responsible paracrine factors are likely large complexes, potentially EVs [7].

- Anti-inflammatory Cytokines: Conditioned media contains factors that significantly suppress the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in the ischemic myocardium and in LPS-stimulated cardiomyocytes [5]. This anti-inflammatory activity contributes to reduced adverse remodeling and creates a more favorable environment for repair.

- Metabolic Modulators: Emerging evidence indicates that stem cell secretions can correct metabolic dysregulation in ischemic heart disease, including disorders of glucose metabolism, fatty acid oxidation, and branched-chain amino acid catabolism [8]. These modulations help restore energy production in stressed cardiomyocytes.

Therapeutic Effects of Conditioned Media in Experimental Models

Cardioprotection in Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

Multiple experimental studies across different species have demonstrated the potent cardioprotective effects of stem cell conditioned media in acute ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury models:

- Infarct Size Reduction: In a porcine model of I/R injury, intravenous and intracoronary administration of human MSC-conditioned medium (MSC-CM) resulted in a dramatic 60% reduction in infarct size, associated with significantly improved systolic and diastolic cardiac performance assessed by echocardiography and pressure-volume loops [7]. Similarly, in a mouse I/R model, systemic delivery of SHED-CM significantly attenuated the infarct area/area at risk ratio by 55.1% compared to controls [5].

- Biomarker Improvement: SHED-CM treatment significantly reduced circulating troponin I levels, a sensitive marker of myocardial injury, at 24 hours after reperfusion [5]. This indicates reduced ongoing cardiomyocyte death following the ischemic insult.

- Functional Recovery: Echocardiographic assessment demonstrated that SHED-CM treatment significantly increased left ventricular fractional shortening in mice at 7 days after myocardial I/R compared to control-treated animals [5].

Table 1: Quantitative Cardioprotective Effects of Stem Cell Conditioned Media in Experimental Ischemia-Reperfusion Models

| Conditioned Media Source | Experimental Model | Key Protective Outcomes | Proposed Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) [7] | Porcine I/R injury | 60% reduction in infarct size; Improved systolic/diastolic function | Reduced oxidative stress; Decreased TGF-β signaling and apoptosis |

| Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth (SHEDs) [5] | Mouse I/R injury | 55% reduction in infarct size; Reduced troponin I; Improved fractional shortening | Suppressed apoptosis; Anti-inflammatory effects; HGF-mediated protection |

| Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) [6] | In vitro & ex vivo rat I/R | Reduced cell injury (LDH activity); Improved cell viability (MTT) | Paracrine activation of PI3K pathway |

| Dental Pulp Stem Cells [5] | Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (hypoxia/serum deprivation) | 63.5% reduction in TUNEL-positive cells under hypoxia | HGF-dependent anti-apoptotic pathway |

Anti-Apoptotic and Anti-Inflammatory Actions

Conditioned media mediates powerful cytoprotective effects on cardiomyocytes exposed to ischemic stress:

- Apoptosis Suppression: In the border zone of myocardial infarction, where cardiomyocytes are at risk of delayed cell death, SHED-CM treatment significantly reduced the frequency of TUNEL-positive myocytes [5]. In vitro studies using neonatal rat cardiac myocytes subjected to hypoxia/serum-deprivation demonstrated that SHED-CM suppressed apoptosis by 63.5% under hypoxic conditions [5]. This anti-apoptotic effect was significantly stronger than that provided by bone marrow-derived or adipose-derived stem cell conditioned media [5].

- Inflammation Modulation: In the ischemic heart in vivo, SHED-CM administration attenuated the I/R-induced increases in cardiac TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β mRNA levels [5]. In cultured cardiac myocytes, SHED-CM pretreatment dose-dependently suppressed LPS-induced expression of these pro-inflammatory genes [5].

- Mechanistic Insights: The potent anti-apoptotic activity of SHED-CM was significantly attenuated by HGF neutralization, both in vitro and in vivo, identifying HGF as a critical mediator of this protective effect [5]. Similarly, the protection afforded by MSC-CM in vitro was significantly reduced by PI3K inhibitors (LY294002 or Wortmannin), but not by neutralizing antibodies against IGF-1 or VEGF, suggesting a central role for PI3K/Akt pathway activation in MSC-CM-mediated protection [6].

Not all conditioned media provides equivalent cardioprotection. Systematic comparisons reveal important source-dependent differences:

- Superior Efficacy of SHED-CM: In direct comparative studies, SHED-CM exhibited stronger anti-apoptotic actions and better improvement of cell viability under serum-deprived conditions compared to conditioned media from bone marrow-derived stem cells (BMSC-CM) or adipose-derived stem cells (ADSC-CM) [5].

- Cytokine Profile Variations: Cytokine antibody arrays and ELISA validation demonstrated that SHED-CM contains a significantly higher concentration of HGF than BMSC-CM and ADSC-CM, providing a mechanistic explanation for its superior anti-apoptotic potency [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Conditioned Media from Different Stem Cell Sources

| Parameter | SHED-CM | BMSC-CM | ADSC-CM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-apoptotic potency [5] | Strongest (63.5% reduction under hypoxia) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Effect on cell viability (serum-deprivation) [5] | Significant improvement | No effect | No effect |

| Anti-inflammatory action [5] | Potent suppression of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β | Similar potency | Similar potency |

| HGF concentration [5] | Highest | Lower | Lower |

| Therapeutic infarct size reduction [5] | 55% | Not reported | Not reported |

Experimental Protocols for Conditioned Media Research

Conditioned Media Preparation Protocol

Standardized methodology for generating therapeutic conditioned media is essential for experimental reproducibility and eventual clinical translation:

- Cell Culture: Isolate and expand therapeutic stem cells (e.g., MSCs, SHEDs) under defined conditions using standard culture media. Use low passage numbers (e.g., passages 3-5) to maintain cell potency and prevent senescence-related functional decline.

- Serum Deprivation: Once cells reach 70-80% confluence, wash with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and replace standard growth media with serum-free basal media. Serum deprivation is critical to eliminate confounding factors from fetal bovine serum and to create a defined therapeutic product.

- Conditioning Phase: Incubate cells in serum-free media for 24-72 hours (typically 48 hours) to allow secretion of paracrine factors into the conditioned media. Maintain appropriate control conditions using serum-free media incubated without cells.

- Collection and Clarification: Collect conditioned media and remove cellular debris by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 20 minutes followed by filtration through 0.22 µm filters.

- Concentration and Storage: Concentrate conditioned media using centrifugal filter devices (e.g., 3-5 kDa molecular weight cut-off) if desired. Aliquot and store at -80°C until use. Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles to preserve bioactivity.

In Vivo Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Model

The efficacy of conditioned media is typically evaluated in well-established animal models of myocardial I/R injury:

- Animal Preparation: Anesthetize animals (typically mice or rats) and perform endotracheal intubation for mechanical ventilation throughout the surgical procedure.

- Thoracotomy: Perform a left thoracotomy between the fourth and fifth ribs to expose the heart.

- Coronary Artery Ligation: Identify the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) and ligate it temporarily using a slipknot with a piece of tubing to facilitate reperfusion. Place the suture approximately 2-3 mm from the origin of the LAD. Ischemia is confirmed by visual observation of myocardial blanching and ECG changes (ST-segment elevation).

- Reperfusion: After 30-60 minutes of ischemia (duration depends on specific model), release the ligation to allow reperfusion, confirmed by visible hyperemia in the previously ischemic territory.

- Treatment Administration: Intravenously administer conditioned media or control media (e.g., 100-200 µL for mice) 5 minutes after reperfusion initiation [5]. Alternative administration routes include intracoronary infusion [7].

- Functional and Histological Assessment: At predetermined endpoints (e.g., 24 hours for infarct size measurement, 1-4 weeks for functional assessment), evaluate outcomes using echocardiography, hemodynamic measurements, histology (TTC staining for infarct size), and molecular analyses.

In Vitro Cardioprotection Assays

Mechanistic studies utilize controlled in vitro systems to dissect specific protective pathways:

- Cardiomyocyte Culture: Isolate neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes or use established cardiomyocyte cell lines. Culture under standard conditions until experiments.

- Hypoxia/Serum Deprivation Model: Replace normoxic culture media with deoxygenated, glucose-free balanced salt solutions and place cells in a hypoxic chamber (1% O₂, 5% CO₂, 94% N₂) for 6-24 hours to simulate ischemic conditions. Include serum deprivation to enhance metabolic stress.

- Conditioned Media Treatment: Add conditioned media or control media at the initiation of hypoxia or at the "reoxygenation" phase when returning to normoxic, complete media.

- Assessment of Apoptosis: Quantify apoptosis using TUNEL staining, caspase-3/7 activity assays, or Annexin V/propidium iodide flow cytometry after 24-48 hours of treatment.

- Cell Viability Measurement: Assess overall cell viability using metabolic assays such as MTT or WST-8 at 24-48 hours post-treatment [5].

- Pathway Inhibition Studies: Utilize specific pharmacological inhibitors (e.g., PI3K inhibitors LY294002 or Wortmannin [6]) or neutralizing antibodies (e.g., anti-HGF antibody [5]) to interrogate mechanistic pathways.

Experimental Workflow for Conditioned Media Research

Signaling Pathways in Conditioned Media-Mediated Cardioprotection

Conditioned media activates multiple interconnected pro-survival signaling pathways in recipient cardiomyocytes:

PI3K/Akt Pathway

The PI3K/Akt pathway emerges as a central mediator of conditioned media-induced cardioprotection. Experimental evidence demonstrates that the protective effects of MSC-CM are significantly attenuated by PI3K inhibitors (LY294002 or Wortmannin) [6]. Akt activation phosphorylates numerous downstream targets including GSK-3β, Bad, and caspase-9, collectively inhibiting mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening and apoptosis execution. This pathway integrates signals from various growth factors present in conditioned media, creating a powerful anti-apoptotic signal.

Growth Factor-Specific Signaling

Specific growth factors enriched in conditioned media activate distinct protective pathways:

- HGF/c-Met Signaling: HGF, particularly abundant in SHED-CM, activates its receptor c-Met, triggering multiple downstream pathways including PI3K/Akt, STAT3, and MAPK cascades [5]. HGF signaling promotes cardiomyocyte survival, inhibits pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members, and enhances cellular repair mechanisms. Neutralization studies confirm that HGF depletion significantly attenuates the anti-apoptotic actions of SHED-CM [5].

- IGF-1 Signaling: While MSC-CM protection appears independent of IGF-1 based on neutralizing antibody studies [6], IGF-1 remains a potentially important component that may activate Akt and modulate cellular metabolism and survival in other contexts.

- VEGF Signaling: Similarly, VEGF neutralization does not abolish MSC-CM protection [6], suggesting that while VEGF may contribute to angiogenic effects, it is not the primary mediator of acute cardioprotection against I/R injury.

Anti-Inflammatory Signaling

Conditioned media suppresses the activation of pro-inflammatory transcription factors including NF-κB, reducing the expression of cytokines like TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β [5]. This modulation of the inflammatory response limits secondary tissue damage and creates a more favorable environment for repair processes. The specific factors responsible for this immunomodulation are an active area of investigation, with HGF, TGF-β, and various EV-contained microRNAs as likely contributors.

Metabolic Modulation

Emerging evidence indicates that stem cell secretions can correct pathological metabolic remodeling in ischemic heart disease [8]. Conditioned media components may enhance glucose uptake and utilization via GLUT1/GLUT4 upregulation, modulate fatty acid oxidation through AMPK/PGC-1α signaling, and improve mitochondrial function [8]. These metabolic improvements help restore energy production in stressed cardiomyocytes, supporting contractile function and cell survival.

Signaling Pathways in Conditioned Media-Mediated Protection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Conditioned Media Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|

| PI3K Pathway Inhibitors | LY294002, Wortmannin [6] | Mechanistic studies of signaling pathways | Identified PI3K activation as essential for MSC-CM protection [6] |

| Growth Factor Neutralizing Antibodies | Anti-HGF, Anti-IGF-1, Anti-VEGF [6] [5] | Identification of critical bioactive factors | Established HGF as key mediator of SHED-CM anti-apoptotic effects [5] |

| Apoptosis Detection Kits | TUNEL Assay, Caspase-3/7 Activity, Annexin V/PI [5] | Quantification of cardiomyocyte death | Demonstrated 63.5% reduction in apoptosis with SHED-CM [5] |

| Cell Viability Assays | MTT, WST-8 [6] [5] | Assessment of overall cell health | Confirmed CM improves cardiomyocyte viability under stress [5] |

| Cytokine Array/Analysis | Cytokine Antibody Array, ELISA, RT-PCR [5] | Comprehensive profiling of CM components | Revealed superior HGF content in SHED-CM vs other sources [5] |

| EV Isolation Tools | Ultracentrifugation, Size-Exclusion Chromatography, Filtration [1] [7] | Separation and analysis of vesicular fractions | Identified >1000 kDa fraction as protective component [7] |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Standardization and Manufacturing Hurdles

The transition of conditioned media therapies from research to clinical application faces several significant challenges:

- Production Standardization: Critical parameters including cell source, passage number, culture conditions, serum deprivation duration, and concentration methods require standardization to ensure batch-to-batch consistency [3] [4]. The lack of standardized protocols currently hampers reproducibility and direct comparison between studies.

- Potency and Quality Control: Developing robust potency assays that correlate with therapeutic efficacy is essential for quality control. Such assays may target specific growth factor concentrations, EV counts, or functional responses in standardized cellular assays.

- Scalable Manufacturing: Transitioning from laboratory-scale production to clinically relevant volumes under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) conditions presents substantial technical and regulatory challenges [3] [4].

Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Therapeutics

Future developments will likely focus on engineering approaches to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of conditioned media:

- Preconditioning Strategies: Exposing stem cells to specific environments (hypoxia, inflammatory cytokines, pharmacological agents) before conditioned media collection can enhance the potency of their secretions by upregulating beneficial factors [4].

- Engineered Extracellular Vesicles: EVs can be engineered to enhance cardiac targeting, prolong circulation half-life, and deliver specific recombinant therapeutic cargoes [1] [2]. These modifications may tilt the cardiac regeneration field further toward these novel, defined cell-free biologics.

- Biomaterial-Assisted Delivery: Incorporating conditioned media components into biomaterial scaffolds or hydrogels can create sustained-release systems that prolong therapeutic exposure at the injury site, potentially enhancing regenerative outcomes [4].

Clinical Translation Landscape

The clinical pipeline for cardiac regeneration remains dominated by cell-based approaches, but cell-free strategies are emerging. A recent analysis of ClinicalTrials.gov (August 2025) identified 23 registered interventional trials focusing on cardiac regeneration, with most being early-phase, investigator-led studies [9]. While no large-scale clinical trials exclusively testing conditioned media were identified in this analysis, the promising preclinical data summarized in this review provides a compelling rationale for such trials. The established safety profile of cell-free approaches may accelerate their clinical translation compared to cell-based therapies.

The field of cardiac regeneration has undergone a fundamental paradigm shift from cell-based to cell-free therapeutic strategies. The limitations of cell transplantation—particularly poor survival, safety concerns, and logistical complexity—have driven this transition toward harnessing the paracrine secretions of therapeutic cells. Compelling preclinical evidence demonstrates that stem cell conditioned media and its components, particularly extracellular vesicles, can significantly reduce myocardial infarct size, attenuate apoptosis, suppress inflammation, and improve cardiac function in models of ischemia-reperfusion injury. The activation of pro-survival pathways including PI3K/Akt and the involvement of specific growth factors like HGF provide mechanistic insights into these protective effects. While challenges in standardization, manufacturing, and clinical translation remain, cell-free therapies based on stem cell secretions represent a promising direction for myocardial protection and regeneration that may ultimately offer safe, effective, and clinically practical treatments for patients with ischemic heart disease.

The therapeutic paradigm for myocardial protection is shifting from whole stem cell transplantation to the use of a cell-free secretome—the complex mixture of bioactive factors released by stem cells into conditioned medium. This in-depth technical guide deconstructs the secretome's composition, production, and mechanisms of action within the context of cardiac repair. We provide a comprehensive analysis of key secretory components, detailed experimental workflows for secretome characterization, and standardized methodologies for evaluating therapeutic efficacy in cardiovascular disease models. By synthesizing current proteomic data and functional studies, this whitepaper serves as an essential resource for researchers and drug development professionals advancing next-generation cardioprotective therapies.

Stem cell-based therapy has emerged as a promising strategy for treating myocardial injury and cardiomyopathy, conditions characterized by irreversible cardiomyocyte loss and pathological remodeling that leads to heart failure [10]. While stem cells demonstrate significant therapeutic potential, their clinical application faces substantial challenges including poor survival after transplantation, limited engraftment, and potential safety concerns [10]. Consequently, research focus has pivoted toward understanding that the beneficial effects of stem cells are predominantly mediated through paracrine secretions rather than direct cell replacement [10] [11].

This secretome, composed of proteins, growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, enzymes, and extracellular vesicles containing RNA, lipids, and proteins, represents a novel "cell-free" therapeutic approach [11]. The conditioned medium (CM) containing these secretions has demonstrated significant cardioprotective capabilities, including improving cardiac function after myocardial infarction, increasing myocardial capillary density, reducing infarct size, and preserving systolic and diastolic performance [12]. In myocardial protection research, the secretome offers a promising strategy to harness the regenerative capacity of stem cells while overcoming the limitations of cell-based therapies.

Core Bioactive Components of the Secretome

The therapeutic potential of the secretome in myocardial protection is mediated through its diverse bioactive components, which act synergistically to promote cardiac repair and regeneration.

Proteinaceous Components and Growth Factors

Proteomic analyses of stem cell secretomes have identified numerous proteins critical for cardiac repair. Table 1 summarizes the key protein classes and their demonstrated functions in myocardial protection.

Table 1: Key Proteinaceous Components in Cardioprotective Secretomes

| Protein Class | Key Examples | Primary Functions in Myocardial Protection | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Factors | VEGF, HGF, G-CSF, Angiopoietin | Angiogenesis, cardiomyocyte survival, anti-apoptosis | Increased capillary density (981±55 vs 645±114 capillaries/mm²; p=0.021) in MI porcine model [12] |

| Anti-inflammatory Factors | IL-10, TGF-β, PGE2 | Macrophage polarization to M2 phenotype, inflammation resolution | Enhanced M2 macrophage activation, reduced interferon-γ and IL-4 expression [10] [11] |

| Regulatory Proteins | Sirtuins, Nucleic acid metabolism proteins (376 identified), Protein modifying enzymes (292 identified) | Metabolic reprogramming, epigenetic regulation | Ferroptosis key in cardiac mesoderm; sirtuin signaling drives cardiomyocyte fate [13] |

| Metabolic Enzymes | Glycolytic enzymes, Fatty acid β-oxidation enzymes | Energy substrate switching, mitochondrial protection | Cluster analysis shows transition from glycolytic profile in iPSC-CMs to fatty acid oxidation enrichment [13] |

Extracellular Vesicles and Non-Coding RNAs

Beyond soluble proteins, the secretome contains extracellular vesicles (EVs) including exosomes and microvesicles that serve as intercellular communication vehicles. These EVs carry cargo including:

- microRNAs (e.g., anti-fibrotic miRNAs, pro-angiogenic miRNAs)

- Lipids and metabolites that influence recipient cell metabolism

- Proteins that exert enzymatic or signaling functions

These components directly target pathological processes in the injured myocardium. For instance, MSC-derived exosomes have been shown to directly target TGF-βR2, reducing Smad2 phosphorylation and exerting potent anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects both in vivo and in vitro [10]. Similarly, secretome-derived non-coding RNAs regulate multiple pro-proliferative pathways to promote cardiomyocyte proliferation [14].

Experimental Workflows for Secretome Production and Analysis

Standardized methodologies are crucial for generating reproducible, therapeutically relevant secretomes for myocardial protection research.

Secretome Production and Collection

Figure 1: Workflow for Secretome Production and Characterization

The production workflow begins with critical decisions that significantly influence secretome composition and therapeutic potency:

Cell Source Selection: Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) from bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord represent the most common sources, though induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived macrophages and other progenitors are emerging alternatives [10] [14].

Culture Method Optimization:

- 3D vs. 2D Culture: 3D culture systems more closely mimic the physiological environment and enhance anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic, and tissue regeneration properties. Secretomes from 3D microtissue models demonstrate enhanced mineralization capacity and homogenous distribution across scaffolds compared to 2D counterparts [11].

- Oxygen Concentration: Physiological hypoxia (1-10% O₂) maintains multipotency, enhances proliferation, and promotes regenerative/cytoprotective effects through HIF-1α upregulation, which increases production of vascularization factors (VEGF, angiotensin) [11].

- Biochemical Stimulation: Preconditioning with inflammatory factors (IFN-γ, TNF-α) increases anti-inflammatory and regenerative factors including IL-6, TGF-β, VEGF, HGF, and G-CSF, redirecting cell metabolism to the glycolytic pathway and enhancing immunomodulatory factor secretion [11].

Serum-Free Conditioning: To minimize interferences from animal serum components, cells are transitioned to serum-free medium for a defined conditioning period (typically 24-72 hours) before conditioned medium collection [11].

Processing, Characterization, and Standardization

Following collection, conditioned medium undergoes processing and rigorous characterization:

Processing Methods: Ultrafiltration-based fractionation (0.2µm–50 kDa) effectively isolates fractions enriched in exosomes and proteins, preserving functionally significant secretome components while excluding larger or smaller biomolecules [15]. Concentration methods include tangential flow filtration, centrifugal concentrators, and lyophilization.

Proteomic Characterization: Multiplexed tandem mass tag (TMT)-based mass spectrometry enables comprehensive quantitative analysis. A recent study identified 4,433 unique proteins during cardiomyocyte differentiation, with 62% showing significant alterations during the differentiation process [13]. Unsupervised clustering reveals distinct protein expression patterns corresponding to key biological processes at each developmental stage.

Quality Control Metrics: Include total protein quantification, nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) for vesicle concentration and size distribution, electron microscopy (TEM/SEM) for vesicle morphology, and functional potency assays.

Signaling Mechanisms in Myocardial Protection

The cardioprotective effects of the secretome are mediated through complex signaling networks that target multiple pathological processes simultaneously.

Figure 2: Key Signaling Pathways in Secretome-Mediated Myocardial Protection

The molecular mechanisms through which secretome components exert cardioprotective effects include:

Anti-Fibrotic Signaling: MSC-derived exosomes directly target transforming growth factor beta receptor 2 (TGF-βR2), reducing phosphorylation of Smad2 and exerting potent anti-fibrotic activity in vitro and in vivo [10].

Angiogenic Activation: Secretome-induced HIF-1α upregulation increases production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and angiopoietin, enhancing capillary density and myocardial perfusion after infarction [11] [12].

Anti-Apoptotic Pathways: Sirtuin signaling activation promotes cardiomyocyte survival and drives cardiomyocyte fate specification, particularly during cardiac mesoderm development [13].

Immunomodulation: Secretome components induce CCR2+ and CX3CR1+ macrophage accumulation and polarization toward the regenerative M2 phenotype, ameliorating local inflammation and improving cardiac fibroblast activity [10].

Proliferative Induction: Primitive macrophage-conditioned medium activates multiple pro-proliferative pathways in adult cardiomyocytes, promoting cell cycle re-entry and regeneration [14].

Functional Assessment in Cardiac Disease Models

Rigorous functional validation is essential to establish therapeutic efficacy. Table 2 summarizes key outcome measures and experimental findings from preclinical studies of secretome-based cardioprotection.

Table 2: Functional Assessment of Secretome Therapeutics in Cardiac Models

| Assessment Method | Key Parameters Measured | Representative Findings | Reference Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Cardiomyocyte Proliferation | EdU/BrdU incorporation, Ki67 staining, cytokinesis analysis | hiPM-cm promoted adult cardiomyocyte proliferation through multiple pro-proliferative pathways | Human cardiomyocytes [14] |

| Cardiac Function (Echocardiography) | LVEF, LVIDd, ±dp/dt | Significant improvements in LVEF, LVIDd, and ±dp/dt after hiPSCs-CM treatment | Myocardial infarction mice [10] |

| Histological Analysis | Capillary density, infarct size, fibrosis extent | Increased capillary density (981±55 vs 645±114 capillaries/mm²; p=0.021), reduced infarct size | Myocardial infarction porcine model [12] |

| Molecular Pathway Analysis | Phosphoprotein profiling, gene expression, pathway enrichment | Identification of 5 key proteins in hiPM-cm mediating proliferative activation; ferroptosis key in CME specification | Proteomic analysis [14] [13] |

| Metabolic Assessment | Glycolytic rates, fatty acid oxidation, mitochondrial function | Transition from glycolytic profile in iPSC-CMs to fatty acid β-oxidation enrichment in mature cardiomyocytes | Metabolic pathway analysis [13] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Secretome Studies in Myocardial Protection

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Culture Media | Human pluripotent stem cell media, Mesenchymal stem cell media, Xeno-free formulations | Maintenance, expansion, and differentiation of stem cell sources | Serum-free and xeno-free formulations essential for clinical translation; chemically defined media provide batch-to-batch consistency [16] [17] |

| Separation & Concentration Systems | Ultrafiltration devices (0.2µm–50 kDa), Tangential flow filtration, Centrifugal concentrators | Isolation of fraction enriched in exosomes and proteins | Ultrafiltration effectively captures small vesicles and mid-sized proteins while excluding larger or smaller biomolecules [15] |

| Proteomic Analysis Tools | Tandem mass tag (TMT) reagents, Nanoflow LC/ESI-MS/MS, Bioinformatics software | Quantitative proteomic profiling, pathway analysis | TMT-based mass spectrometry enabled identification of 4,433 unique proteins during cardiomyocyte differentiation [13] |

| Characterization Assays | Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), ELISA, Western blot, Electron microscopy (TEM/SEM) | Quantification of vesicle concentration, protein identification, morphology assessment | Serum-containing CM exhibits significantly higher levels of total protein, non-vesicular RNA, exosomes, and nanoparticles [15] |

| Functional Assay Kits | HUVEC spheroid angiogenesis assay, Cardiomyocyte proliferation kits, Apoptosis detection assays | Validation of angiogenic, proliferative, and anti-apoptotic activities | HUVEC spheroid assays identified angiogenic properties of MSC-CM; EdU/BrdU incorporation for proliferation [14] [12] |

The systematic deconstruction of the stem cell secretome represents a transformative approach in myocardial protection research. This technical guide has synthesized current methodologies, compositional analyses, and functional validation strategies that enable researchers to harness the therapeutic potential of conditioned medium in cardiovascular applications. The standardized workflows and analytical frameworks presented here provide a foundation for advancing secretome-based therapeutics toward clinical application.

Future directions in this rapidly evolving field include the integration of AI-powered platforms for optimizing secretome formulations, which have already demonstrated 35% increases in cell proliferation rates and 28% reductions in media consumption across large-scale production batches [16]. Additionally, the development of 3D culture systems that more accurately mimic physiological environments and the implementation of real-time monitoring technologies for bioprocess control will further enhance the reproducibility and therapeutic potency of secretome products [11] [16]. As standardization improves and our understanding of mechanism deepens, secretome-based therapies offer promising avenues for addressing the significant unmet clinical needs in myocardial protection and regeneration.

The therapeutic application of stem cell conditioned medium for myocardial protection represents a paradigm shift in cardiovascular regenerative medicine. While stem cells were initially heralded for their differentiation potential, accumulating evidence now identifies their secreted factors, particularly extracellular vesicles (EVs), as the primary mediators of cardiac repair [18] [2]. These nanoscale lipid-bilayer enclosed structures serve as indispensable vehicles for intercellular communication, shuttling bioactive molecules between stem cells and compromised myocardial tissue. Within the context of ischemic heart disease, EVs execute a multifaceted therapeutic program encompassing anti-apoptotic signaling, immunomodulation, angiogenesis promotion, and metabolic reprogramming [8] [2]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical examination of EV biology, mechanistic actions in myocardial protection, standardized experimental methodologies, and translational applications, specifically framed within the investigation of stem cell conditioned medium as a therapeutic agent for cardiac repair.

EV Biogenesis, Classification, and Cargo Composition

Biogenetic Pathways and Cargo Loading

Extracellular vesicles originate through distinct cellular processes that define their physical characteristics and molecular cargo. The major EV subtypes include: (1) Exosomes (30-150 nm), which form via the endosomal pathway through inward budding of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and subsequent fusion with the plasma membrane; (2) Microvesicles (100-1000 nm), generated through direct outward budding and shedding of the plasma membrane; and (3) Apoptotic bodies (1-5 μm), released during programmed cell death [19] [20]. The biogenesis of exosomes, the most well-characterized EV population for therapeutic applications, is regulated by sophisticated molecular machinery including the ESCRT (Endosomal Sorting Complexes Required for Transport) system and various ESCRT-independent mechanisms involving tetraspanins (CD63, CD81, CD9) and ceramide [21]. Cargo loading—encompassing proteins, lipids, DNA, and diverse RNA species—occurs selectively during vesicle formation, reflecting the physiological state of the parent cell and enabling sophisticated communication with recipient cells [19] [20].

Molecular Cargo of Therapeutic EVs

Stem cell-derived EVs, particularly those from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), carry a rich repertoire of bioactive molecules responsible for their cardioprotective effects. The table below summarizes key cargo components identified in therapeutic EVs.

Table 1: Therapeutic Cargo in Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

| Cargo Category | Specific Components | Documented Functions in Myocardial Protection |

|---|---|---|

| MicroRNAs (miRNAs) | miR-21, miR-210, miR-146a, miR-1275 | Inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis, promote angiogenesis, modulate inflammation [22] [23] [24] |

| Growth Factors | VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor), HGF (Hepatocyte Growth Factor), FGF (Fibroblast Growth Factor) | Stimulate angiogenesis, enhance cell survival, promote tissue repair [22] [18] |

| Proteins | IGF-1 (Insulin-like Growth Factor 1), FGF-2, HSP70 (Heat Shock Protein 70) | Promote cardiomyocyte development/survival, cardioprotective signaling [20] [19] |

| Lipids | Cholesterol, sphingomyelin, ceramide | Structural integrity, membrane signaling, microdomain organization [19] |

Mechanisms of Action: EV-Mediated Cardioprotection

Core Protective Pathways

EVs orchestrate myocardial protection through a combination of distinct yet interconnected mechanistic pathways, culminating in enhanced tissue viability and functional recovery following ischemic injury.

Figure 1: Core Cardioprotective Pathways Activated by Stem Cell-Derived EVs. EVs mediate therapeutic effects via multiple parallel mechanisms, including activation of survival signals, promotion of new blood vessels, modulation of immune responses, reprogramming of cardiac metabolism, and inhibition of scar tissue formation, ultimately leading to improved cardiac function.

The PI3K/AKT pathway is a critical survival signaling cascade activated by EV cargo. For instance, exosomal miR-1275 derived from cardiomyocytes was shown to upregulate IL-38 expression in lymphocytes, which in turn activated the PI3K/AKT pathway, leading to decreased expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax and increased expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2, thereby reducing apoptosis in an LPS-induced sepsis model [24]. Furthermore, EVs modulate post-infarct immune responses by promoting polarization of macrophages toward the regenerative M2 phenotype, partly mediated by exosomal miR-132-3p, and by suppressing pro-inflammatory monocyte activation [20]. A third major mechanism involves the amelioration of metabolic disturbances in the ischemic heart. Stem cell-derived EVs can restore balance to substrate utilization by enhancing glucose uptake and oxidation, partly through upregulation of GLUT4 and PKM2, thereby improving cardiac efficiency in a low-oxygen environment [8].

Quantitative Therapeutic Outcomes

The efficacy of EV-based therapies is quantitatively demonstrated through improved functional and structural metrics in preclinical models of myocardial infarction. The following table consolidates key outcome measures from experimental studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of EV Therapy in Preclinical Myocardial Infarction Models

| Therapy Type | Key Cargo / Feature | Reported Efficacy in Preclinical Models | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSC-EVs | miR-21, miR-210, VEGF, HGF | Increased LVEF by 3.8%; Reduced infarct size; Enhanced angiogenesis [22] | Paracrine signaling, anti-apoptosis, angiogenesis |

| iPSC-Derived EVs | Cardiomyocyte-specific miRNAs, proteins | Improved myocardial perfusion; Reduced inflammation and apoptosis [22] [2] | Direct cytoprotection, stimulation of endogenous repair |

| Cardiac Progenitor Cell-EVs | miR-146a, miR-210, miR-132 | Promoted endothelial tube formation; Reduced cardiomyocyte apoptosis; Enhanced cardiac function [22] [23] | Angiogenesis, anti-apoptosis, intercellular communication |

| Engineered EVs (CXCR4-overexpressing) | Enhanced homing capability | Improved myocardial homing efficiency by 5.2-fold [22] | Targeted delivery to ischemic tissue |

Experimental Protocols: Isolating and Characterizing EVs from Conditioned Medium

Standardized Workflow for EV Research

The investigation of EVs from stem cell conditioned medium requires a rigorous and standardized experimental pipeline to ensure the isolation and characterization of bona fide EV populations.

Figure 2: Standardized Workflow for EV Isolation from Conditioned Medium. The critical process begins with collecting conditioned medium from stem cells grown under defined conditions, followed by sequential steps to remove non-vesicular contaminants, concentrate the vesicles, isolate them via high-purity methods, and thoroughly characterize the final EV preparation before functional testing.

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolation of EVs from Stem Cell Conditioned Medium

- Cell Culture and Conditioned Medium Collection: Culture MSCs (or other stem cells) to 70-80% confluence. Replace growth medium with serum-free, exosome-depleted medium. After 24-48 hours, collect the conditioned medium and immediately process or store at 4°C for short periods (-80°C for long-term) [23] [24].

- Pre-Clearation Centrifugation: Centrifuge the conditioned medium at 2,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove dead cells and large debris. Transfer the supernatant to a fresh tube and centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 45 minutes to eliminate larger vesicles and organelles [24].

- Ultracentrifugation-based Isolation: Transfer the double-cleared supernatant to ultracentrifuge tubes. Pellet EVs by ultracentrifugation at 120,000 × g for 70 minutes at 4°C. Carefully discard the supernatant and resuspend the EV pellet in a suitable buffer (e.g., sterile PBS). This step may be repeated for higher purity [24].

- Alternative Isolation Methods: For specific applications, Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) provides superior purity by separating EVs from soluble proteins based on hydrodynamic radius. Alternatively, precipitation-based kits offer convenience but may co-precipitate contaminants like lipoproteins [20].

Protocol 2: Comprehensive Characterization of Isolated EVs

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Dilute the EV suspension in PBS and inject into the NTA system. This analysis determines the particle size distribution (typically 30-200 nm for exosomes) and concentration [19] [20].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Adhere EVs to Formvar-carbon coated grids, negative stain with uranyl acetate, and image. TEM confirms the spherical, cup-shaped morphology and membrane integrity of the vesicles [24].

- Western Blot Analysis: Lyse EVs and perform immunoblotting to detect canonical positive markers (e.g., Tetraspanins: CD63, CD81, CD9; Endosomal proteins: TSG101, Alix) and the absence of negative markers (e.g., organelle-specific proteins like Calnexin) [21] [24].

- Cargo Profiling: Extract total RNA and protein from EVs. Use qRT-PCR to profile specific miRNAs of interest (e.g., miR-21, miR-146a). For unbiased discovery, RNA-Seq or mass spectrometry-based proteomics can be employed to comprehensively map the molecular cargo [20] [24].

Protocol 3: In Vitro Validation of EV-Mediated Cardioprotection

- Model Establishment: Create an in vitro model of myocardial injury. For hypoxia, culture cardiomyocytes (e.g., H9c2 cells or primary cardiomyocytes) in a hypoxic chamber (1% O2) for 6-24 hours. For inflammatory injury, treat cells with LPS (e.g., 500 ng/mL for 3 hours) [24].

- EV Treatment and Uptake Tracking: Treat injured cardiomyocytes with isolated EVs (typical dose: 10-100 μg/mL). To confirm functional delivery, label EVs with a lipophilic dye (e.g., PKH67 or DiI) and visualize their internalization into target cells via confocal microscopy after 6-24 hours [23].

- Functional Assessment:

- Apoptosis Assay: Use an Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis detection kit and flow cytometry to quantify the percentage of apoptotic cells post-EV treatment.

- Cell Viability/Proliferation: Measure using a CCK-8 assay according to manufacturer protocols.

- Mechanistic Signaling Analysis: Perform Western blotting to analyze the activation of key signaling pathways, such as the phosphorylation status of PI3K and AKT, and the expression levels of apoptosis regulators like Bcl-2 and Bax [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for EV Research in Myocardial Protection

| Reagent/Kits | Specific Example | Primary Function in EV Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Serum-Free Medium | DMEM, RPMI-1640 | Production of conditioned medium without serum-derived EV contamination [24] |

| EV-Depleted FBS | Systemically depleted FBS | Supports cell growth during expansion while preventing confounding bovine EV introduction |

| Protease Inhibitors | EDTA-free cocktails | Preserves EV protein cargo integrity during isolation and processing |

| Isolation Kits | ExoQuick-TC, Total Exosome Isolation | Polymer-based precipitation for rapid EV isolation from conditioned medium |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, Anti-CD81, Anti-TSG101 | Detection of positive EV markers via Western Blot for identity validation [24] |

| Negative Marker Antibodies | Anti-Calnexin, Anti-GM130 | Confirms absence of cellular contaminants from endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi |

| EV Labeling Dyes | PKH67, DiI, DiD | Fluorescent labeling for tracking EV uptake and biodistribution in vitro and in vivo |

| RNA Isolation Kits | Trizol-based systems | Efficient extraction of high-quality RNA, including small RNAs, from EV pellets |

| qRT-PCR Assays | TaqMan MicroRNA Assays | Sensitive quantification of specific therapeutic miRNAs (e.g., miR-21, miR-146a) |

Extracellular vesicles represent the defining mechanistic link between stem cell conditioned medium and its observed therapeutic benefits in myocardial protection. Their capacity to coordinate complex reparative processes—from suppressing apoptosis and inflammation to stimulating angiogenesis and correcting metabolic imbalances—underscores their role as central mediators. The translational pathway for EV-based therapies is advancing rapidly, with ongoing efforts focusing on engineering EVs for enhanced targeting and cargo delivery. However, significant challenges related to the standardization of isolation protocols, precise functional characterization, and scalable manufacturing must be systematically addressed to fully realize the clinical potential of EVs as a primary active component in stem cell conditioned medium [2] [20]. As the field moves forward, the integration of EV biology with bioengineering and clinical cardiology promises to unlock novel, effective, and cell-free therapeutic paradigms for ischemic heart disease.

Stem cell-based therapy has emerged as a promising strategy for myocardial protection and regeneration. However, growing evidence indicates that the therapeutic benefits of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are primarily mediated through paracrine factors rather than direct cell replacement [25] [10]. Conditioned medium (CM), which contains the secretory repertoire of MSCs, has demonstrated significant cardioprotective effects in various models of myocardial injury, including ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury and myocardial infarction (MI) [25] [5]. The molecular mechanisms underlying these protective effects involve the coordinated modulation of three critical pathological processes: apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress. This technical review synthesizes current experimental evidence detailing how CM mediates these effects at a molecular level, providing researchers with a comprehensive mechanistic framework and practical experimental guidelines.

Molecular Mechanisms of CM Action

Modulation of Apoptosis

CM exerts potent anti-apoptotic effects primarily through the regulation of caspase activation and the provision of pro-survival growth factors.

Caspase Pathway Inhibition: In aortic rings from brain-dead rats subjected to IR injury, CM preservation significantly lowered immunoreactivity of key apoptotic executers, including caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9 [25]. Additionally, CM reduced mRNA levels of caspase-12, a mediator of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress-induced apoptosis, in vascular grafts from aged rats [26].

HGF-Mediated Protection: Comparative analysis revealed that CM from stem cells of human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHEDs) contained higher concentrations of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) than CM from bone marrow or adipose-derived stem cells [5]. Neutralization of HGF significantly attenuated the anti-apoptotic effects of SHED-CM in cardiac myocytes, establishing HGF as a critical component.

Table 1: Anti-apoptotic Effects of CM in Experimental Models

| Experimental Model | Target Molecule | Effect of CM | Quantitative Change | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD rat aortic rings (IR) | Caspase-3 immunoreactivity | Significant reduction | Reported as decreased | [25] |

| BD rat aortic rings (IR) | Caspase-8 immunoreactivity | Significant reduction | Reported as decreased | [25] |

| BD rat aortic rings (IR) | Caspase-9 immunoreactivity | Significant reduction | Reported as decreased | [25] |

| Aged rat vascular grafts | Caspase-12 mRNA | Significant reduction | Reported as decreased | [26] |

| Neonatal rat cardiac myocytes (hypoxia) | TUNEL-positive cells | Significant reduction | 63.5% decrease | [5] |

| SHED-CM vs. BMSC-CM | HGF concentration | significantly higher | ~2-3 fold increase (ELISA) | [5] |

Regulation of Inflammatory Responses

CM mediates significant anti-inflammatory effects, primarily through the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules.

Cytokine Suppression: In a mouse model of myocardial IR injury, intravenous administration of SHED-CM significantly reduced cardiac mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β [5]. In vitro, SHED-CM pretreatment dose-dependently suppressed LPS-induced expression of these cytokines in cardiac myocytes.

Adhesion Molecule Downregulation: CM preservation of vascular grafts from brain-dead rats significantly decreased mRNA expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM-1), key mediators of leukocyte infiltration during inflammation [25].

Macrophage Modulation: Intracardiac injection of MSCs induced accumulation of CCR2+ and CX3CR1+ macrophages, ameliorating local inflammation and improving fibroblast activity in ischemia-reperfusion-injured hearts [10] [27].

Table 2: Anti-inflammatory Effects of CM in Experimental Models

| Experimental Model | Inflammatory Marker | Effect of CM | Quantitative Change | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse myocardial I/R | Cardiac TNF-α mRNA | Significant reduction | Reported as decreased | [5] |

| Mouse myocardial I/R | Cardiac IL-6 mRNA | Significant reduction | Reported as decreased | [5] |

| Mouse myocardial I/R | Cardiac IL-1β mRNA | Significant reduction | Reported as decreased | [5] |

| BD rat aortic rings | VCAM-1 mRNA | Significant reduction | Reported as decreased | [25] |

| BD rat aortic rings | ICAM-1 mRNA | Significant reduction | Reported as decreased | [25] |

| Ischemia-reperfused hearts | Macrophage accumulation | Induced CCR2+/CX3CR1+ macrophages | Reported as increased | [10] [27] |

Attenuation of Oxidative Stress

CM protects against oxidative damage by reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and mitigating their damaging effects on cellular components.

Reduction of Oxidative Stress Markers: CM preservation of aortic rings from brain-dead rats significantly lowered immunoreactivity of nitrotyrosine, a marker of protein nitration and peroxynitrite-mediated oxidative damage [25]. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) immunoreactivity, an indicator of neutrophil infiltration and oxidative burst, was also significantly reduced.

Antioxidant Defense Enhancement: While not directly measured in CM studies, general mechanisms against oxidative stress in cardiomyopathy include the upregulation of endogenous antioxidant systems such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GPX) [28]. The Nrf2 pathway, a master regulator of antioxidant gene expression, represents a potential target for CM-mediated effects.

Mitochondrial Protection: CM may improve mitochondrial function and reduce ROS production at its source, as mitochondria are the primary contributors to cellular oxidative stress in cardiomyopathies [28].

Integrated Signaling Pathways

The cardioprotective effects of CM involve an integrated network of signaling pathways that coordinately regulate apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress. The diagram below illustrates the key molecular targets and their interactions.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CM Preparation from Bone Marrow-Derived MSCs

The following protocol details the standard methodology for obtaining CM from rat bone marrow-derived MSCs, as described in multiple studies [25] [26]:

- Isolation: Harvest femurs and tibias from 8-12-week-old male Lewis rats. Flush bones with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) to extract bone marrow.

- Culture: Suspend cells in MSC Expansion Medium and incubate at 37°C with 5% CO₂. At 80% confluency, subculture primary cells at a 1:3 ratio.

- Expansion: Use cells at passage 3 for CM collection. At >80% confluency, wash MSCs three times with DPBS to remove serum contaminants.

- Conditioning: Add serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (D-MEM) and incubate for 24 hours.

- Concentration: Collect primary CM and concentrate using ultrafiltration units (4500× g for 4 hours at 4°C).

- Quality Control: Quantify protein concentration via Bradford assay (typically 0.5 mg/mL final concentration). Analyze cytokine content using antibody arrays (e.g., RayBio Biotin Label-based rat antibody array).

In Vitro Models for Assessing CM Efficacy

- Hypoxia/Serum-Deprivation in Cardiac Myocytes: Culture neonatal rat cardiac myocytes under hypoxic conditions (1% O₂) with serum deprivation for 24 hours. Add CM at the onset of hypoxia. Assess apoptosis via TUNEL staining and cell viability using WST-8 assays [5].

- Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-Induced Inflammation: Pretreat cardiac myocytes with CM for 2 hours before adding LPS (typically 100 ng/mL). Measure pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) mRNA levels using quantitative RT-PCR after 6-24 hours [5].

Ex Vivo Models of Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

- Aortic Ring Preparation: Explain thoracic aorta from 15-month-old rats or brain-dead donors. Place in cold Krebs-Henseleit solution. Isolate and clean periadventitial fat, cut into 4-mm rings [25] [26].

- Cold Ischemic Storage: Store rings for 24 hours at 4°C in nitrogen-equilibrated tubes containing physiological saline supplemented with CM or vehicle control.

- Organ Bath Assessment: Mount rings in organ baths with Krebs-Henseleit solution at 37°C, gassed with 95% O₂-5% CO₂. Apply 2 g tension with equilibration for 60 minutes.

- Functional Measurements: Pre-contract rings with phenylephrine (10⁻⁹–10⁻⁵ M). Assess endothelium-dependent relaxation with cumulative acetylcholine (10⁻⁹–10⁻⁵ M). Evaluate endothelial-independent relaxation with sodium nitroprusside.

In Vivo Models of Myocardial Injury

- Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion: Subject mice to 30 minutes of myocardial ischemia followed by 24 hours of reperfusion. Administer CM intravenously 5 minutes after reperfusion [5].

- Infarct Size Measurement: After 24 hours, excise hearts. perfuse with Evans blue dye to delineate area at risk (AAR). Section and incubate with 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) to distinguish infarcted (pale) from viable (red) tissue. Calculate infarct area (IA) as percentage of AAR.

- Functional Assessment: Perform echocardiography at baseline and 7 days post-I/R to measure left ventricular fractional shortening and other functional parameters.

- Molecular Analysis: Collect tissue for TUNEL staining, immunohistochemistry (caspases, MPO, nitrotyrosine), and mRNA quantification of inflammatory markers.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental pipeline from CM preparation to efficacy assessment:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for CM Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (D-MEM), MSC Expansion Medium | CM production, cell maintenance | Provides base medium for conditioning; supports MSC growth and factor secretion |

| Cytokine Screening Tools | RayBio Biotin Label-based Rat Antibody Array, ELISA kits | CM characterization | Identifies and quantifies specific factors (e.g., HGF, VEGF) in CM |

| Apoptosis Detection Kits | TUNEL assay, caspase activity assays, WST-8 cell viability kit | Assessment of anti-apoptotic effects | Quantifies programmed cell death and cell survival in response to CM treatment |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | qRT-PCR primers (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, caspase-12), protein extraction kits | Gene and protein expression analysis | Measures changes in inflammatory and apoptotic markers at transcriptional level |

| Vascular Function Assessment | Acetylcholine, phenylephrine, sodium nitroprusside, organ bath system | Ex vivo vascular reactivity studies | Evaluates endothelium-dependent and independent relaxation in aortic rings |

| Animal Models | Male Lewis rats (8-12 weeks, 15 months), C57BL/6J mice, brain death models | In vivo and ex vivo disease modeling | Provides physiological context for CM efficacy in aged, brain-dead, or I/R-injured systems |

| Histological Stains | Evans blue, 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC), hematoxylin and eosin | Infarct size measurement, tissue morphology | Delineates area at risk and infarcted tissue in myocardial I/R studies |

| Antibodies for Neutralization | Anti-HGF neutralizing antibody | Mechanistic studies | Validates contribution of specific factors to CM's protective effects |

The molecular mechanisms through which CM modulates apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress involve a complex interplay of multiple factors targeting specific pathways. The coordinated inhibition of caspase activation, suppression of pro-inflammatory mediators, and reduction of oxidative damage markers collectively contribute to CM's cardioprotective efficacy. The experimental methodologies outlined provide a robust framework for researchers to investigate these mechanisms further and develop standardized protocols for CM-based therapeutic applications. Future research should focus on identifying optimal CM compositions for specific cardiac pathologies and developing engineered CM with enhanced therapeutic potential.

Stem cell conditioned medium (CM) has emerged as a promising cell-free therapeutic for myocardial protection, with its efficacy largely attributed to the paracrine release of extracellular vesicles (EVs), particularly exosomes. The therapeutic potential of these vesicles is primarily mediated by their microRNA (miRNA) cargo, which orchestrates complex protective signaling pathways in recipient cardiac cells. This technical guide synthesizes current evidence on key miRNAs—including miR-21, miR-24-3p, miR-126, and others—that are enriched in stem cell-derived EVs and demonstrates potent cardioprotective effects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. We detail the molecular mechanisms by which these miRNAs regulate apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and angiogenesis, providing comprehensive experimental protocols for profiling EV-miRNA cargo and validating functional targets. Through structured data presentation and pathway visualization, this review equips researchers with the methodological framework needed to advance the development of miRNA-based therapeutics for cardiac repair, positioning stem cell CM as a viable platform for next-generation cardiovascular regenerative medicine.

Cardiovascular disease, particularly acute myocardial infarction (MI), remains a leading cause of death worldwide despite advances in reperfusion therapies [1] [29]. The adult human heart possesses limited regenerative capacity, losing approximately one billion cardiomyocytes following an MI event, which frequently leads to heart failure [1]. While stem cell transplantation initially promised significant cardiac regeneration, growing evidence indicates that therapeutic benefits are primarily mediated through paracrine mechanisms rather than direct cell engraftment and differentiation [30].

Stem cell conditioned medium has emerged as a critical vehicle for these paracrine factors, with extracellular vesicles—especially exosomes (30-150 nm)—serving as key mediators of intercellular communication [1] [31]. EVs are membrane-bound nanoparticles that transport functional cargo including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, with microRNAs representing particularly potent regulators of gene expression in recipient cells [30]. These small non-coding RNAs (approximately 22 nucleotides) function as "master post-transcriptional regulators" by binding complementary sequences in target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or mRNA degradation [32].

The investigation of EV-miRNAs in myocardial protection represents a paradigm shift from cell-based to biomolecule-based therapeutics. This whitepaper comprehensively examines the miRNA cargo within stem cell-derived EVs, delineating its role in regulating protective signaling pathways against myocardial injury. By integrating current experimental evidence and methodological approaches, we aim to provide researchers with a foundational resource for advancing this promising frontier in cardiovascular medicine.

Key miRNA Players in Cardioprotection

Comprehensive profiling of stem cell-derived EV cargo has identified several miRNAs that consistently demonstrate cardioprotective properties through the regulation of distinct signaling pathways. The table below summarizes the most therapeutically promising miRNAs, their regulated processes, and demonstrated functional outcomes.

Table 1: Key Cardioprotective miRNAs in Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

| miRNA | Primary Source | Regulated Processes | Key Validated Targets | Experimental Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21-5p | MSC-EVs, Cardiomyocyte-CM [33] [31] | Anti-apoptosis, Anti-inflammation, Fibrosis reduction | PDCD4, PTEN [33] | ↓ Infarct size, ↓ Cardiomyocyte apoptosis (20-30%), ↑ Cardiac function [33] |

| miR-24-3p | ADSC-EVs, HUCMSC-Exos [34] [30] | Anti-apoptosis, Oxidative stress reduction | Nrf2 pathway [34] | ↓ Infarct size (∼50%), ↓ Inflammation, ↑ Antioxidant capacity [34] |

| miR-126 | EPC-EVs, Skeletal muscle-EVs [35] [31] | Angiogenesis, Endothelial function | SPRED1, VEGF pathway [31] | ↑ Capillary density, ↑ Endothelial cell proliferation/migration [35] |

| miR-29b | HUCMSC-Exos [30] | Anti-fibrosis | COL1A1, COL3A1, FBN1 [30] | ↓ Collagen deposition, ↓ Fibrosis [30] |

| miR-210 | Hypoxia-preconditioned MSC-EVs [31] | Angiogenesis, Hypoxia tolerance | Casp8ap2 [31] | ↑ Angiogenesis, ↑ Cell survival under hypoxia [31] |

| let-7 family | MSC-EVs [32] [36] | Insulin signaling, Metabolism | Multiple targets in insulin pathway [36] | Regulation of metabolic function [36] |

The miRNAs presented in Table 1 represent the most consistently identified and functionally validated species across multiple studies. Of particular note is miR-21, which is upregulated in conditioned medium from oxygen-glucose-deprived cardiomyocytes and demonstrates significant protective effects when transferred to recipient cells [33]. Depletion of miR-21 from conditioned medium substantially reduces its protective capacity against oxidative stress and fibroblast activation, confirming its functional importance [33].

Similarly, miR-24-3p has been identified as a critical component in adipose-derived stem cell nanovesicles, where it mediates cardioprotection through the Nrf2 pathway, enhancing antioxidant capability and reducing inflammatory response in injured myocardium [34]. The transfer of these miRNAs via EVs represents a sophisticated natural mechanism for coordinated regulation of cardiac repair processes across different cell types.

Experimental Protocols for miRNA Cargo Analysis

Rigorous characterization of EV-miRNA cargo and functional validation of its targets require integrated experimental approaches. Below, we detail standardized methodologies for isolation, profiling, and functional analysis of miRNAs from stem cell conditioned medium.

EV Isolation and Characterization from Conditioned Medium

Protocol 1: Sequential Ultracentrifugation for EV Isolation

- Conditioned Medium Collection: Culture stem cells (e.g., MSCs, ADSCs) to 70-80% confluence. Replace with serum-free medium for 48 hours. Collect CM and perform sequential centrifugations [33].

- Debris Removal: Centrifuge at 300 × g for 10 min at 4°C → Transfer supernatant → Centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 20 min → Transfer supernatant → Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 30 min [37].

- EV Pellet Collection: Ultracentrifuge the resulting supernatant at 100,000 × g for 90 min at 4°C [33].

- EV Washing: Resuspend pellet in PBS → Ultracentrifuge again at 100,000 × g for 90 min [33].

- Characterization: Validate EV identity using Nanosight LM10 for size distribution (30-150 nm for exosomes), TEM for morphology, and Western blotting for markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, flotillin-1, Alix) [37].

Protocol 2: Commercial Kit Alternative

- Sample Preparation: Process CM through initial centrifugation steps as in Protocol 1 to remove cells and debris.

- EV Isolation: Use exoEasy kit (QIAGEN) per manufacturer's instructions [37].

- Quality Assessment: Quantify particle concentration (∼10^7-10^8 particles/μg protein expected) and confirm presence of EV markers [34].

miRNA Profiling and Functional Validation

Protocol 3: Small RNA Sequencing and Analysis

- RNA Isolation: Extract total RNA from isolated EVs using miRNeasy Kit (QIAGEN) with spiking of Cel-miR-39-3p as an external control [37].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Use platforms such as NanoString nCounter or Illumina sequencing following manufacturer protocols [32] [37].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

Protocol 4: Functional Validation of miRNA Targets

- Gain/Loss-of-Function Studies: Transfert donor cells with miRNA mimics (20-40 nM) or inhibitors (e.g., anti-miR-21: 5'-UAGCUUAUCAGACUGAUGUUGA-3') using X-tremeGENE siRNA transfection reagent [33].

- Target Validation: Use dual-luciferase reporter assays with wild-type and mutant 3'UTR constructs of predicted targets.

- Phenotypic Assessment: Evaluate functional outcomes including:

Signaling Pathways Regulated by miRNA Cargo

The therapeutic effects of EV-miRNAs are mediated through the coordinated regulation of multiple interconnected signaling pathways. The following diagrams illustrate the principal mechanisms by which key miRNAs confer cardioprotection.

miR-21-Mediated Anti-Apoptotic and Anti-Fibrotic Signaling

Figure 1: miR-21 mediated cardioprotection. miR-21 transferred via stem cell EVs inhibits PDCD4 and PTEN, leading to reduced apoptosis and fibrosis [33] [31].

miR-24-3p Regulation of Oxidative Stress via Nrf2 Pathway

Figure 2: miR-24-3p antioxidant pathway. miR-24-3p activates Nrf2 pathway, enhancing antioxidant defense and reducing cell death [34].

Angiogenic Regulation by miR-126 and miR-210

Figure 3: Angiogenic miRNA pathways. miR-126 and miR-210 promote angiogenesis through distinct signaling pathways [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful investigation of EV-miRNA function requires specific reagents and methodologies. The following table compiles essential research tools referenced across key studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for EV-miRNA Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| EV Isolation Kits | exoEasy Kit (QIAGEN) [37] | EV purification from conditioned medium | Membrane-based affinity purification of intact EVs |

| RNA Isolation Kits | miRNeasy Kit (QIAGEN) [37] | Small RNA extraction from EVs | Comprehensive recovery of miRNA species |

| miRNA Inhibitors | Anti-miR-21-5p: 5'-UAGCUUAUCAGACUGAUGUUGA-3' (Ambion AM10206) [33] | miRNA loss-of-function studies | Sequence-specific inhibition of endogenous miRNA activity |

| Transfection Reagents | X-tremeGENE siRNA Transfection Reagent (Roche) [33] | Delivery of miRNA mimics/inhibitors to cells | Efficient intracellular nucleic acid delivery with low toxicity |

| EV Characterization | Nanosight LM10 (Malvern) [37], Transmission Electron Microscope [37] | EV size and concentration analysis | Nanoparticle tracking and morphological validation |

| Sequencing Platforms | NanoString nCounter [32], Illumina Sequencers [37] | miRNA expression profiling | Multiplexed quantification of miRNA species |

| Animal MI Models | Left Coronary Artery Ligation (rat) [33], Myocardial I/R (mouse) [34] | In vivo validation of cardioprotection | Preclinical assessment of therapeutic efficacy |

The miRNA cargo within stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles represents a sophisticated endogenous system for regulating protective signaling pathways in myocardial tissue. Through coordinated modulation of apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and angiogenesis, these tiny RNA molecules exert powerful effects that belie their size. The experimental frameworks and mechanistic insights presented in this technical guide provide researchers with the foundational knowledge needed to advance this promising field.

As research progresses, several frontiers warrant particular attention: the development of engineered EVs with enhanced cardiac targeting, the optimization of scalable production methods for clinical translation, and the exploration of miRNA cocktail approaches that might surpass the efficacy of single miRNAs. With ongoing advances in EV bioengineering and miRNA delivery systems, harnessing the regulatory potential of miRNA cargo offers a promising path toward effective cell-free therapies for myocardial protection and regeneration.

From Lab to Preclinical Models: Protocols and Evidence for CM Efficacy