Stem Cell-Derived Beta Cells for Type 1 Diabetes: A Comprehensive Review of Efficacy, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the efficacy of stem cell-derived beta cells as a curative therapy for type 1 diabetes (T1D), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development...

Stem Cell-Derived Beta Cells for Type 1 Diabetes: A Comprehensive Review of Efficacy, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the efficacy of stem cell-derived beta cells as a curative therapy for type 1 diabetes (T1D), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational science establishing proof-of-concept, detailing how allogeneic stem cell-derived islets can restore endogenous insulin production and physiologic glucose control. The review examines methodological advances in cell delivery, including hepatic portal vein infusion and encapsulation devices, alongside their respective requirements for immunosuppression. It critically addresses persistent challenges in immunogenicity, scalability, and safety, evaluating troubleshooting strategies such as the development of hypoimmune cells through genetic engineering. Finally, the article presents a comparative validation of recent clinical trial outcomes, synthesizing efficacy and safety data to assess the current standing and future trajectory of this transformative therapeutic modality.

The Scientific Foundation: Establishing Proof-of-Concept for Beta Cell Replacement

For decades, the destruction of insulin-producing pancreatic beta cells has been the recognized pathophysiological cornerstone of Type 1 Diabetes (T1D), creating an absolute dependence on exogenous insulin for survival [1]. While insulin therapy is life-saving, it fails to fully mimic physiological insulin regulation, often resulting in suboptimal glycemic control and long-term complications [1] [2]. Beta cell replacement therapy emerged as a strategy to restore endogenous insulin production and achieve long-term glycemic stability. The field is now undergoing a transformative paradigm shift: moving from a reliance on scarce donor pancreatic islets toward the use of stem cell-derived beta cells as a scalable, engineered source for replacement therapy [3] [4]. This shift addresses the fundamental limitation of donor organ shortage, which has historically restricted islet transplantation to a select group of patients with severe hypoglycemic unawareness [2] [5]. This guide objectively compares the performance of traditional islet transplantation against emerging stem cell-derived beta cell therapies, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the key experimental data, protocols, and analytical tools needed to navigate this evolving landscape.

Comparative Analysis of Beta Cell Sourcing Strategies

The transition from donor-dependent to engineered cell sources represents a fundamental change in the therapeutic approach to T1D. The table below provides a direct comparison of the core characteristics of these two strategies.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Islet Transplantation vs. Stem Cell-Derived Beta Cells

| Characteristic | Donor Islet Transplantation | Stem Cell-Derived Beta Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Source | Cadaveric pancreata [2] | Human pluripotent stem cells (embryonic or induced) [1] [2] |

| Key Limitation | Severe donor organ shortage [2] [5] | Requires differentiation and potential genetic engineering [1] [6] |

| Scalability | Limited and fixed supply [4] | Theoretically unlimited, on-demand production [2] [6] |

| Standardization | High variability between donors and isolations [2] | Potential for standardized, quality-controlled cell products [3] |

| Immunosuppression | Lifelong, systemic immunosuppression required [2] [5] | Currently required for allogeneic products; strategies to obviate it are in development [3] [6] |

| Clinical Status | Established therapy for specific T1D patients [2] [5] | Late-stage clinical trials; largely experimental but rapidly advancing [1] [7] |

Efficacy and Clinical Outcomes

Recent clinical trials provide the first robust, quantitative data on the performance of stem cell-derived islets, allowing for a direct comparison with the outcomes of established donor islet transplantation.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Clinical Trial Outcomes

| Parameter | Donor Islet Transplantation (Established Protocol) | Stem Cell-Derived Islets (Zimislecel, Phase 1-2 Trial) |

|---|---|---|

| Study Reference | Shapiro et al., Edmonton Protocol [2] | Reichman et al., 2025 NEJM [3] [7] |

| Sample Size | 36 subjects [2] | 12 subjects (full-dose cohort) [7] |

| Insulin Independence (1 Year) | 44% of recipients [2] | 83% of recipients [3] [7] |

| Freedom from Severe Hypoglycemia | Significant reduction established [2] [5] | 100% of participants free from events [3] [7] |

| HbA1c Reduction | Improvement in metabolic control [2] | Mean decrease of 1.81% [3] |

| Time in Target Glucose Range | Improved stability [2] | >70% to >90% time in range (70-180 mg/dL) [3] [7] |

| C-peptide Positivity | Indicates engraftment and function | Achieved in 100% of participants post-infusion [7] |

The data indicate that stem cell-derived islets can not only meet but potentially exceed the efficacy of donor islets in key metrics, particularly in the rate of insulin independence. However, the safety profile differs. The zimislecel trial reported two deaths, one from cryptococcal meningitis linked to immunosuppression, highlighting that the reliance on chronic immunosuppression remains a significant risk with current allogeneic stem cell products [3] [7].

Technical and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Differentiation of Stem Cells into Beta-Like Cells

This protocol generates insulin-producing beta-like cells from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) by mimicking in vivo pancreatic development [2].

- Definitive Endoderm Induction: Treat hPSCs with Activin A (a TGF-β family member) and Wnt3a to direct differentiation into definitive endoderm cells. This typically lasts 3 days [2].

- Primitive Gut-Tube Formation: Expose the definitive endoderm to Fibroblast Growth Factor 10 (FGF10) and KAAD-cyclopamine (a hedgehog signaling inhibitor) for several days to pattern the cells into primitive gut-tube endoderm [2].

- Pancreatic Progenitor Commitment: Further differentiate the cells using retinoic acid to promote posterior foregut fate and inhibit Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling to drive specification into pancreatic endoderm and endocrine precursors [2].

- Endocrine Differentiation and Maturation: Culture the pancreatic progenitors in a complex cocktail of growth factors, hormones, and signaling molecules to finalize their maturation into endocrine cells expressing insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin [2].

- In Vivo Maturation (Optional): For some protocols, cells are transplanted at the pancreatic endoderm progenitor stage into an in vivo environment (e.g., immunodeficient mice) where vascularization and other host factors support final maturation into functional, glucose-responsive beta cells [2].

Protocol 2: Generation of Hypoimmune Stem Cell-Derived Beta Cells

This protocol uses genetic engineering to create beta cells that evade immune rejection, aiming to eliminate the need for immunosuppression [3] [6].

- Base Cell Line Generation: Start with a human Pluripotent Stem Cell (hPSC) line. Using CRISPR-Cas9, create knock-out mutations in the B2M (Beta-2 Microglobulin) and CIITA (Class II Major Histocompatibility Complex Transactivator) genes. This disrupts surface expression of HLA Class I and Class II molecules, preventing T-cell recognition [6].

- "Don't Eat Me" Signal Knock-in: At the same genomic loci, knock-in genes for immune tolerogenic ligands. A common strategy is the overexpression of CD47, which ligates SIRPα on macrophages and neutrophils to inhibit phagocytosis [3] [6].

- NK Cell Inhibition Knock-in: To protect against Natural Killer (NK) cell-mediated lysis (triggered by "missing self" from HLA Class I knockout), knock-in genes for non-classical HLA molecules like HLA-E or HLA-G, which engage inhibitory receptors on NK cells [6].

- Differentiation into Beta Cells: Differentiate the engineered hypoimmune hPSC line into insulin-producing beta-like cells using a protocol similar to the one described in Section 4.1.

- Validation: Validate immune evasion through in vitro co-culture assays with human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and in vivo transplantation into humanized mouse models without immunosuppression [6].

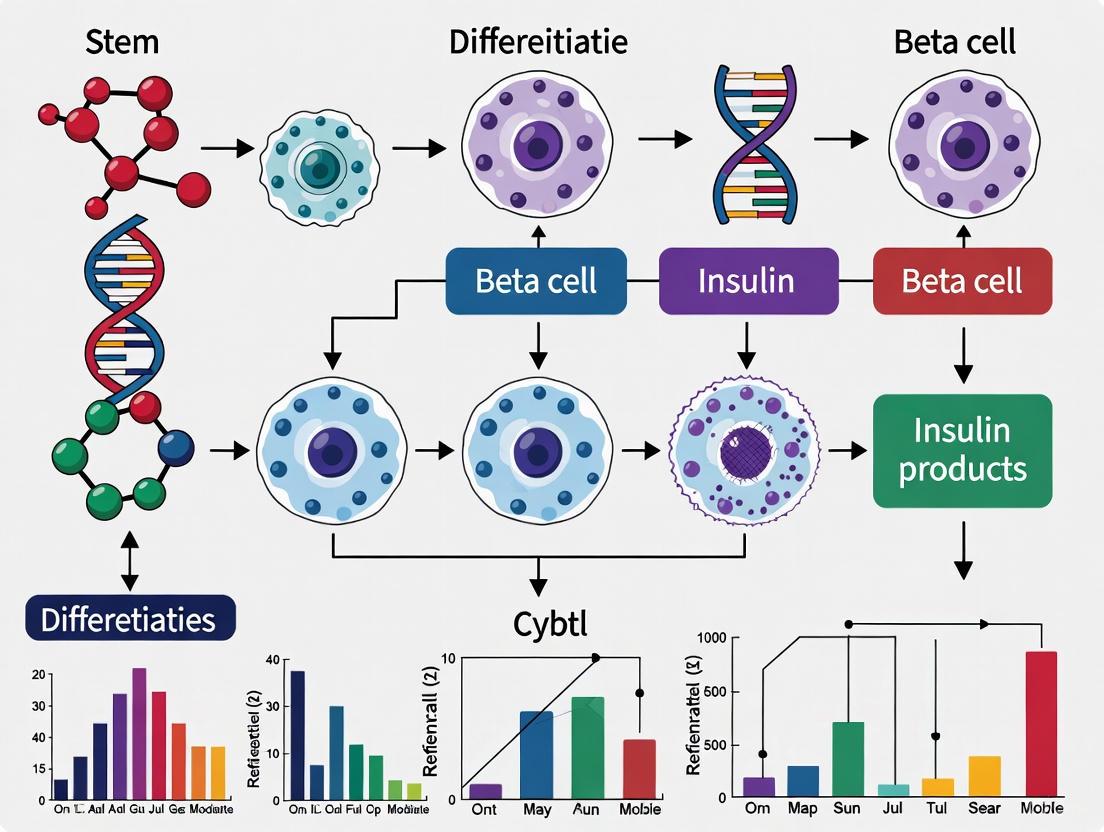

Diagram 1: Hypoimmune Beta Cell Engineering Workflow.

Signaling Pathways in Differentiation and Immune Evasion

The successful generation and transplantation of stem cell-derived beta cells hinge on the precise manipulation of key biological pathways. The diagram below illustrates the core signaling pathways involved in beta cell differentiation and the engineered pathways for immune evasion.

Diagram 2: Key Signaling Pathways in Beta Cell Differentiation and Immune Evasion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Advancing research in this field requires a specific toolkit of biological reagents, assay systems, and delivery devices. The following table details key solutions and their applications for researchers developing and testing stem cell-derived beta cell therapies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Beta Cell Therapy Development

| Reagent/Tool Solution | Primary Function | Application in Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs) | Self-renewing, pluripotent starting material for differentiation [2]. | Source for generating beta-like cells; can be engineered (e.g., hypoimmune) [6]. |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Patient-specific pluripotent cells reprogrammed from somatic cells [2]. | Enables autologous therapy models and disease-in-a-dish research for T1D [2]. |

| Activin A, FGF10, Retinoic Acid | Key signaling molecules for directed differentiation [2]. | Used in vitro to guide hPSCs through stages of pancreatic development. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Precision gene-editing tool [6]. | Engineering hypoimmune traits (e.g., B2M KO, CD47 KI) in hPSC lines [6]. |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Immunomodulatory and pro-angiogenic accessory cells [8] [5]. | Co-transplanted with islets to potentially enhance graft survival and function [8]. |

| Macroencapsulation Devices | Physical, semi-permeable barriers for housing islet cells [2]. | Protects transplanted cells from immune attack while allowing nutrient/insulin exchange. |

| Mixed-Meal Tolerance Test (MMTT) | Standardized challenge to stimulate insulin secretion. | Measures C-peptide levels in vivo to confirm engraftment and functional beta cell mass [7]. |

| Immunosuppressive Regimens (e.g., ATG, MMF) | Suppresses host adaptive immune system. | Required in clinical trials for allogeneic cell transplant to prevent graft rejection [1] [7]. |

The paradigm in beta cell sourcing has irrevocably shifted. Traditional islet transplantation provided critical proof-of-concept that beta cell replacement can restore physiological glucose control, but its scalability was inherently limited [2] [4]. Stem cell-derived beta cells now represent a scalable, engineered solution that has transitioned from scientific aspiration to clinical reality, demonstrating remarkable efficacy in early trials [3] [7]. The next frontier lies in resolving the dual challenges of immune rejection and scalability. Strategies like hypoimmune gene editing offer a promising path to eliminate the burdens and risks of lifelong immunosuppression [3] [6]. For the research community, the focus must now expand beyond achieving scientific feasibility to addressing the "last mile" challenges of manufacturing, cost, and accessibility to ensure these transformative therapies can reach the millions of individuals living with T1D [4].

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by the selective destruction of insulin-producing β-cells in the pancreatic islets of Langerhans, resulting in the inability to produce and secrete insulin in response to blood glucose levels [9]. For decades, the standard treatment has relied on exogenous insulin administration, which, while life-saving, fails to replicate the precise dynamics of physiological insulin secretion and places a significant burden on patients [9]. Stem cell-derived islets (SC-islets) have emerged as a transformative therapeutic approach aimed at providing a "functional cure" by replacing the lost β-cell mass [9]. This strategy circumvents the fundamental limitation of conventional islet transplantation—the critical shortage of donor pancreata—by offering a potentially unlimited source of insulin-producing cells [2]. This guide examines the mechanisms through which SC-islets restore endogenous insulin production, objectively comparing their performance against established alternatives and detailing the experimental methodologies used to evaluate their efficacy.

Comparative Analysis of Beta-Cell Replacement Therapies

The landscape of beta-cell replacement has evolved from solid organ pancreas transplants to cell-based therapies. The table below provides a structured comparison of the primary modalities.

Table 1: Comparison of Beta-Cell Replacement and Insulin Therapy Strategies for Type 1 Diabetes

| Therapy | Mechanism of Action | Efficacy Data | Key Limitations | Immunosuppression Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exogenous Insulin | Subcutaneous injection/infusion of insulin to lower blood glucose. | Maintains life but fails to fully mimic physiological control; high risk of hypoglycemia [9]. | Does not restore endogenous production; requires constant patient management [9]. | Not required. |

| Pancreas Transplant | Surgical transplantation of a whole pancreas from a deceased donor. | Restores insulin independence; considered the gold standard for glycemic control [2]. | Highly invasive surgery; significant procedural risks; limited donor availability [2]. | Lifelong immunosuppression required. |

| Donor Islet Transplant | Infusion of islets isolated from donor pancreata into the liver via the portal vein. | The Edmonton Protocol demonstrated insulin independence in all 7 patients at 1 year [9]. NIH-sponsored trials show effectiveness in reducing hypoglycemia [2]. | Requires multiple donors per recipient; limited donor availability; gradual decline in function over time [9] [2]. | Lifelong immunosuppression required. |

| Stem Cell-Derived Islets (SC-Islets) | Transplantation of in vitro-differentiated, insulin-producing islets. | Phase 1/2 trial of VX-880: 92% mean insulin use reduction; 10 of 12 patients achieved insulin independence [10]. | Challenges with post-transplant cell survival (e.g., hypoxia); potential for immune rejection [11] [12]. | Required for current non-encapsulated products; strategies for evasion in development [10] [12]. |

Mechanisms of Functional Restoration by SC-Islets

SC-islets restore glucose homeostasis by replicating the core functions of native pancreatic islets. The mechanism can be broken down into a multi-stage process.

Core Functional Mechanism

The mechanism begins with 1. Glucose Sensing. Mature SC-β cells express high levels of glucose transporters (e.g., GLUT1) and glucokinase (GK), which allow them to rapidly equilibrate intracellular glucose concentrations with the blood and initiate glycolysis, respectively [12]. This leads to 2. Metabolic Signaling, a critical stage where SC-β cells utilize oxidative phosphorylation to metabolize glucose. The nuclear receptor ERRγ has been identified as a key driver of this metabolic maturation, enhancing the capacity for mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [12]. This process generates ATP, increasing the ATP/ADP ratio, which in turn triggers the closure of ATP-sensitive K+ channels and membrane depolarization. This depolarization opens voltage-gated calcium channels, causing a Ca²⁺ Influx that is the key signal for 3. Insulin Secretion [12]. Finally, the synthesized insulin is released via exocytosis (4. Glucose Homeostasis), thereby restoring physiological glycemic control. The entire process is governed by the activation of a Native β-cell Network of transcription factors, including NKX6.1, PDX1, and MAFA, which are essential for establishing and maintaining β-cell identity and functional maturity [12].

Key Experimental Models and Protocols

Evaluating the in vivo functionality of SC-islets relies on standardized preclinical models and clinical assessments. The following workflow outlines a standard protocol for a diabetes reversal study in immunodeficient mice, a cornerstone experiment for validating SC-islet potency.

Preclinical Animal Model

The gold-standard protocol for assessing SC-islet function in vivo involves several key stages [2] [12]:

- Diabetes Induction: Immunodeficient mice (e.g., NOD-scid or similar) are rendered diabetic by administration of streptozotocin (STZ), a toxin that selectively destroys their endogenous insulin-producing β-cells.

- Hyperglycemia Confirmation: Mice are considered diabetic and ready for transplantation once stable hyperglycemia (blood glucose >350 mg/dL) is established.

- Transplantation: SC-islets are transplanted into a suitable site in the mouse, most commonly under the kidney capsule or via infusion into the portal vein, which leads to engraftment in the liver.

- Efficacy Monitoring: Blood glucose levels are monitored regularly. Successful engraftment and function of the SC-islets is demonstrated by a sustained return to normoglycemia (blood glucose <200 mg/dL). This is considered a "functional cure."

- Confirmation of Graft Function: To conclusively prove that the normoglycemia is due to the human SC-islet graft, the graft is surgically removed (explantation). The subsequent return to hyperglycemia confirms graft-dependent diabetes reversal.

Clinical Trial Assessment

In human trials, efficacy is measured by several key endpoints [10]:

- Stimulated C-peptide: The gold-standard metric for endogenous insulin production. Patients undergo a Mixed Meal Tolerance Test (MMTT), and the resulting C-peptide levels (a byproduct of insulin synthesis) are measured.

- Glycated Hemoglobin (A1C): Measures long-term glycemic control, with a target of <7% indicating good control.

- Time-in-Range (TIR): The percentage of time blood glucose levels remain within the target range (70-180 mg/dL), as measured by continuous glucose monitors. A TIR >70% is a key goal.

- Insulin Dose: The reduction, or complete elimination, of the need for exogenous insulin injections.

Table 2: Key Clinical Outcomes from Recent SC-Islet Trials

| Trial / Study | Patient Population | Intervention | Primary Efficacy Outcomes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FORWARD (VX-880) Phase 1/2 [10] | 12 adults with T1D and impaired hypoglycemia awareness. | Single infusion of fully differentiated SC-islets into the liver + immunosuppression. | - Stimulated C-peptide- A1C <7%- TIR >70%- Insulin use. | - Endogenous insulin restored in all 12.- 92% mean reduction in insulin use.- 10/12 patients achieved insulin independence. |

| PEC-Direct (ViaCyte) [9] | Adults with T1D (multiple sites). | Implantation of pancreatic progenitor cells (PEC-01) in a non-immune-protective device + immunosuppression. | - Meal-responsive C-peptide. | - C-peptide production detected 6-9 months post-transplant.- Grafts matured into endocrine cells in vivo. |

| Autologous CiPSC-Islets [1] [13] | A single patient with T1D for 11 years. | Transplantation of islets derived from the patient's own chemically reprogrammed stem cells. | - Insulin independence.- A1C <7%.- Safety. | - Insulin independence achieved on day 75.- Sustained A1C ≤5.7% for one year. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Advancing SC-islet research requires a specific set of reagents and tools to generate, characterize, and test the cells. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments and the broader field.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SC-Islet Research and Development

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Usage in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Small Molecules & Growth Factors | Guide pluripotent stem cells through stages of pancreatic differentiation by activating/inhibiting key pathways. | Activin A (definitive endoderm), FGF10 (gut-tube endoderm), KAAD-cyclopamine (hedgehog inhibition), Retinoic Acid (pancreatic endoderm) [2] [12]. |

| Immunosuppressive Drugs | Suppress the host immune system to prevent rejection of allogeneic cell transplants in clinical trials. | Protocols often use a combination like thymoglobulin (induction) and mycophenolate mofetil (maintenance) [2] [12]. |

| EDN3 (Endothelin 3) | Protects SC-β cell identity and function under hypoxic stress post-transplantation by modulating maturation and glucose-sensing genes [11]. | Used in in vitro studies to enhance SC-islet survival and function by overexpressing EDN3 before transplantation into low-oxygen environments [11]. |

| ERRγ Agonists | Promotes metabolic maturation of SC-β cells by enhancing mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, which is critical for glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [12]. | Forced expression of ERRγ in SC-β cells in vitro to improve their ATP production and subsequent insulin secretion capacity before transplantation [12]. |

| Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion (GSIS) Assay | In vitro functional test that measures the ability of SC-islets to secrete insulin in response to high glucose challenges, a hallmark of mature β-cell function [11]. | SC-islets are sequentially exposed to low glucose, high glucose, and then depolarizing agents (e.g., KCl) while measuring insulin in the supernatant via ELISA. |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite promising results, several challenges remain. A significant hurdle is the poor survival and function of SC-islets post-transplantation due to local hypoxia (low oxygen), particularly in subcutaneous sites or within encapsulation devices [11]. Research shows that hypoxia causes SC-β cells to gradually lose their identity markers, such as insulin, and undergo a metabolic shift away from aerobic respiration, severely impairing insulin secretion [11]. Strategies to overcome this, such as overexpressing protective genes like EDN3, are under active investigation [11].

Another major focus is solving the problem of immune rejection. Current approaches require chronic immunosuppression, which carries significant risks [10] [12]. Future strategies aim to create "immune-shielded" SC-islets through:

- Encapsulation Devices: Physical barriers that protect the cells from immune attack while allowing nutrient and insulin exchange [9].

- Genetic Engineering: Modifying SC-islets to evade the immune system, for example by adding protective genes or using a "safety switch" to eliminate the cells if needed [10].

- Inducing Immune Tolerance: Innovative approaches, so far demonstrated in mice, use a combined transplant of blood stem cells and islets from the same donor to create a "hybrid" immune system that accepts the graft without long-term immunosuppression [14].

Finally, as the field progresses from proof-of-concept to widespread treatment, significant challenges in scalability, cost, and accessibility must be addressed to ensure these transformative therapies can reach the millions of patients in need [4].

In the rapidly advancing field of stem cell-derived beta cell therapy for Type 1 Diabetes (T1D), the objective assessment of therapeutic efficacy relies on a triad of critical biomarkers. The success of these innovative treatments is quantified through precise measurements of C-peptide for beta cell function, HbA1c for long-term glycemic control, and Time-in-Range (TIR) for daily glucose management. These biomarkers provide complementary insights, enabling researchers and drug development professionals to rigorously evaluate whether stem cell-based interventions can restore physiological insulin production and achieve clinically meaningful metabolic outcomes. This guide examines the technical specifications, experimental protocols, and success thresholds for each indicator, contextualized with data from recent clinical trials of stem cell-derived therapies.

C-Peptide: The Gold Standard for Beta Cell Function

Physiological Role and Clinical Significance

C-peptide (connecting peptide) is a 31-amino-acid polypeptide that is cleaved from proinsulin during insulin synthesis in pancreatic beta cells. It is secreted in equimolar amounts to endogenous insulin, serving as a direct marker of insulin production [15] [16]. Unlike insulin, C-peptide has negligible hepatic extraction and a longer half-life (20-30 minutes versus 3-5 minutes for insulin), making it a more stable and reliable measure of beta cell function, especially in insulin-treated patients where it avoids cross-reaction with exogenous insulin assays [16].

In T1D, C-peptide measurement provides crucial information about the residual beta cell function and is the primary endpoint for evaluating the success of beta cell replacement therapies. The restoration of C-peptide secretion following stem cell therapy indicates engraftment, differentiation, and functional maturation of the transplanted cells [17] [18].

Measurement Protocols and Interpretation

Table 1: C-Peptide Measurement Methods and Diagnostic Thresholds

| Method | Procedure | Advantages | Limitations | Clinical Thresholds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting C-Peptide | Measurement after 8-10 hour fast | Easy to standardize, practical | May miss functional capacity | <0.075 nmol/L indicates severe deficiency [16] |

| Random C-Peptide | Measurement without fasting preparation | Simple, convenient for clinics | Interpretation depends on time from last meal | <0.2 nmol/L suggests insulin deficiency [16] |

| Glucagon Stimulation Test (GST) | 1 mg IV glucagon with C-peptide measurement at 0 and 6 minutes | High sensitivity and specificity, short duration | Nausea as side effect | >0.2 nmol/L post-stimulation indicates preserved function [16] |

| Mixed Meal Tolerance Test (MMTT) | Liquid meal consumption with serial measurements over 120 minutes | Physiological stimulus, research gold standard | Time-consuming, requires specialized preparation | Peak >0.2 nmol/L indicates clinically meaningful function [15] [18] |

C-Peptide in Stem Cell Therapy Trials

In recent stem cell therapy trials, C-peptide measurement has been instrumental in demonstrating efficacy:

- In a groundbreaking trial of chemically induced pluripotent stem cell-derived islets (CiPSC-islets), the patient's fasting C-peptide increased from 0 to 721.6 pmol/L (approximately 0.72 nmol/L), exceeding the normal healthy range (300-600 pmol/L) and correlating with insulin independence [17].

- In the PEC-Direct trial of encapsulated stem cell-derived pancreatic endoderm cells, three of ten patients achieved C-peptide levels ≥0.1 nmol/L by month 6, which was associated with improved continuous glucose monitoring measures and reduced insulin dosing [18].

- The threshold of ≥0.2 nmol/L after stimulation is widely considered clinically significant as it associates with fewer complications and less severe hypoglycemia [15].

HbA1c: The Long-Term Glycemic Control Marker

Biochemical Basis and Clinical Utility

Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) forms when hemoglobin non-enzymatically binds to glucose in the bloodstream. It reflects average blood glucose levels over the preceding 2-3 months, corresponding to the lifespan of red blood cells. HbA1c is expressed as a percentage of total hemoglobin, with lower values indicating better glycemic control [17] [19].

For T1D management, the American Diabetes Association recommends a general HbA1c target of <7.0% for most adults, with more stringent targets (<6.5%) potentially appropriate for some patients if achievable without significant hypoglycemia [17].

HbA1c in Stem Cell Therapy Efficacy Assessment

In stem cell therapy trials, HbA1c reduction demonstrates the ability of transplanted cells to provide sustained glycemic control:

- In the CiPSC-islet trial, the patient's HbA1c decreased from 7.57% to 4.76% within one year post-transplantation, well below the success threshold of >7% [17].

- Vertex Pharmaceuticals' stem cell-derived therapy (Zimislecel) reported that 10 of 12 participants who received a full dose achieved HbA1c <7% alongside insulin independence at one year [20].

- HbA1c provides crucial evidence of durable glycemic control beyond immediate post-transplant effects, making it essential for evaluating long-term therapeutic success.

Time-in-Range: The Continuous Glucose Monitoring Metric

Definition and Clinical Relevance

Time-in-Range (TIR) is a continuous glucose monitoring (CGM)-derived metric representing the percentage of time that glucose levels remain within a target range, typically 70-180 mg/dL (3.9-10.0 mmol/L). This real-world measure captures glycemic variability that may not be reflected in HbA1c [17] [18].

Complementary CGM metrics include:

- Time-Above-Range (TAR): >180 mg/dL (>10.0 mmol/L)

- Time-Below-Range (TBR): <70 mg/dL (<3.9 mmol/L)

- Glucose Management Indicator (GMI): Estimated HbA1c from CGM data [18]

TIR as a Stem Cell Therapy Outcome Measure

TIR has emerged as a critical endpoint in recent stem cell therapy trials due to its sensitivity to daily glucose fluctuations:

- In the CiPSC-islet case study, TIR improved from 43.18% at baseline to over 98% at one year post-transplantation, demonstrating remarkable restoration of physiological glucose regulation [17].

- The PEC-Direct trial reported that responders with C-peptide ≥0.1 nmol/L showed significant increases in TIR, with one patient improving from 55% to 85% by month 12 [18].

- Clinical consensus considers TIR >70% as the target for well-controlled T1D, making it a valuable benchmark for assessing stem cell therapy efficacy [18].

Integrated Success Metrics in Recent Clinical Trials

Table 2: Efficacy Outcomes from Recent Stem Cell Therapy Trials for T1D

| Trial / Therapy | C-Peptide Outcomes | HbA1c Outcomes | Time-in-Range Outcomes | Additional Efficacy Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CiPSC-Islets [17] | Increased from 0 to 721.6 pmol/L (fasting) | Decreased from 7.57% to 4.76% | Improved from 43.18% to >98% | Insulin independence achieved by day 75 |

| PEC-Direct (Encapsulated) [18] | 3/10 patients achieved ≥0.1 nmol/L (stimulated) | GMI improved in responders | Increased from 55% to 85% (best responder) | Reduced insulin dosing in responders |

| Vertex VX-880 (Zimislecel) [20] | Not specified | <7% in 10/12 patients at 1 year | >70% in 10/12 patients at 1 year | Insulin independence in 10/12 patients at 1 year |

| PEC-01 Cells [1] | Significant increase by week 26 (p=0.0026) | Not specified | Improved by 13% (p<0.001) | 20% reduction in insulin requirements (p<0.001) |

Experimental Protocols for Efficacy Assessment

Standardized Metabolic Function Tests

Mixed Meal Tolerance Test (MMTT) Protocol:

- Preparation: 10-12 hour overnight fast

- Baseline samples: Collect blood for C-peptide, glucose at t=-10 and t=0 minutes

- Stimulus administration: Liquid meal (e.g., Boost or Sustacal) consumed within 5 minutes

- Serial sampling: Collect blood at 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes post-stimulus

- Sample processing: Centrifuge within 30 minutes, freeze plasma at -20°C until analysis

- Analysis: Measure C-peptide via standardized immunoassay [15] [18]

Glucagon Stimulation Test Protocol:

- Preparation: 10-12 hour overnight fast

- Baseline sample: Collect blood for C-peptide at t=0 minutes

- Stimulus administration: Intravenous glucagon (1 mg) over 2 minutes

- Post-stimulation sample: Collect blood at t=6 minutes

- Sample processing: Centrifuge promptly, freeze plasma for analysis [16]

C-Peptide Assay Standardization Considerations

Significant variability exists between C-peptide assay methods despite common traceability to the WHO International Reference Reagent (IRR 84/510). Between-method coefficients of variation average 19.1% with manufacturers' usual calibration, improving to 7.5% after recalibration with secondary reference materials. Researchers should verify their local laboratory's assay methodology and reference ranges for consistent interpretation [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Beta Cell Function Assessment

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Application Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-Peptide Immunoassay Kits | Quantification of C-peptide in serum/plasma/urine | Assessment of beta cell function in vitro and in vivo | Select assays with <10% proinsulin cross-reactivity; verify detection limit (<0.0025 nmol/L) [15] [16] |

| HbA1c Testing Systems | Measurement of glycated hemoglobin | Long-term glycemic control assessment | Standardize to NGSP/IFCC reference methods; account for hemoglobin variants [17] [19] |

| Continuous Glucose Monitoring Systems | Real-time interstitial glucose measurement | Time-in-Range calculation in clinical trials | Use factory-calibrated systems (e.g., Dexcom G7) with 5-minute sampling intervals [20] [18] |

| Stem Cell Differentiation Kits | Directed differentiation of pluripotent stem cells to beta cells | Generation of insulin-producing cells for transplantation | Monitor key transcription factors (PDX1, NKX6.1, NKX2.2) during differentiation [17] [1] |

| Immunosuppressive Agents | Prevention of graft rejection in allogeneic transplants | Essential for non-encapsulated cell therapies | Consider regimens including anti-thymocyte globulin, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus [18] [21] |

Logical Framework for Efficacy Assessment

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between stem cell therapy and the key efficacy metrics, highlighting how successful engraftment leads to measurable physiological outcomes:

The comprehensive assessment of stem cell-derived beta cell therapies requires multimodal evaluation through C-peptide, HbA1c, and Time-in-Range metrics. These indicators provide complementary information: C-peptide directly measures beta cell functional capacity, HbA1c reflects long-term glycemic control, and TIR captures daily glucose variability. Recent clinical successes demonstrate that these biomarkers can collectively document the transition from exogenous insulin dependence to restored physiological glucose regulation. As stem cell therapies advance toward clinical adoption, standardized application of these efficacy metrics will be essential for validating therapeutic potential and comparing outcomes across different technological platforms.

For decades, the restoration of functional pancreatic islets in patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) has been a primary objective of regenerative medicine. The field is now transitioning from foundational science to tangible clinical applications, with early-phase trials reporting unprecedented success in restoring endogenous insulin production. This guide compares the most recent and compelling clinical evidence for emerging stem cell-derived beta cell therapies, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed analysis of experimental protocols, efficacy data, and safety profiles.

Comparative Efficacy of Leading Therapeutic Candidates

The table below summarizes key efficacy outcomes from recent landmark clinical trials and studies, highlighting the rapid advancement in this domain.

Table 1: Comparison of Efficacy Outcomes from Recent Clinical Trials of Beta-Cell Replacement Therapies

| Therapy / Candidate | Study Phase / Type | Key Efficacy Outcome(s) | Insulin Independence | C-Peptide Response | Glycemic Control (HbA1c) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zimislecel (VX-880) [7] | Phase 1/2 Clinical Trial | 83% (10/12) of participants achieved primary endpoint; restored physiologic islet function. | 83% at Day 365 | Detected post-infusion (from undetectable at baseline) | >70% Time-in-Range (70-180 mg/dL); HbA1c <7% |

| Stem Cell-Derived Islets (Vertex) [21] | Phase 1/2 Clinical Trial (Case Report) | Insulin independence achieved in first patient by day 270. | Achieved (1/1 reported) | Restored | 5.2% |

| Hybrid Immune System (Stanford) [14] | Preclinical (Mouse Model) | Cured or prevented autoimmune diabetes in all mice; no immunosuppression required. | 100% (9/9 cured) | N/A (Preclinical) | N/A (Preclinical) |

| PEC-01 Pancreatic Endoderm Cells [21] | Phase 1/2 Clinical Trial | Meal-responsive C-peptide increased significantly by Week 26; insulin requirements reduced by 20%. | Not achieved | Significant increase | 13% improvement in Time-in-Range |

The data indicates a paradigm shift, with therapies like zimislecel demonstrating not only safety and engraftment but also a high rate of insulin independence—a previously elusive goal [7]. Simultaneously, innovative approaches targeting the underlying autoimmunity, such as the Stanford "immune system reset," show transformative potential by potentially eliminating the need for chronic immunosuppression [14].

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Understanding the distinct methodologies behind these breakthroughs is crucial for evaluating their mechanistic value and translational potential.

Protocol: Allogeneic Stem Cell-Derived Islet Infusion (e.g., Zimislecel)

This protocol underlies the recent Phase 1/2 results published by Vertex Pharmaceuticals [7] [21].

- Cell Product: Allogeneic stem cell-derived, fully differentiated islet cells (zimislecel).

- Dosing: A single infusion of 0.8 × 10^9 cells into the hepatic portal vein.

- Immunosuppression: Glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen administered to all participants to prevent allograft rejection.

- Primary Endpoints: Safety, freedom from severe hypoglycemic events, HbA1c <7% or reduction of ≥1 percentage point, and insulin independence between days 180 and 365.

- Engraftment Assessment: Serum C-peptide levels measured during a 4-hour mixed-meal tolerance test to confirm islet function.

Protocol: Hybrid Immune System with Combined Transplant (Stanford)

This preclinical protocol represents a novel strategy aimed at curing autoimmunity, not just replacing cells [14].

- Pre-conditioning Regimen: A "gentle" regimen involving immune-targeting antibodies, low-dose radiation, and the addition of a drug used to treat autoimmune diseases. This avoids the harsh chemotherapy typically used in bone marrow transplants.

- Transplantation: Combined infusion of blood stem cells and pancreatic islet cells from an immunologically mismatched donor.

- Mechanism of Action: Creates a chimeric or hybrid immune system comprising cells from both the donor and recipient. This resets the immune system, halting the autoimmune attack on islet cells and preventing graft-versus-host disease.

- Outcome: Animals were cured of established diabetes or protected from developing it, without the need for ongoing immune-suppressive drugs.

The core difference between these strategies is visualized below, contrasting the cell replacement approach with the immune reset strategy.

Analysis of Safety and Tolerability

The safety profiles of these therapies are critical for risk-benefit analysis and are summarized below.

Table 2: Comparison of Safety Profiles and Key Challenges

| Therapy / Candidate | Reported Adverse Events | Immunosuppression Requirement | Major Challenges & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zimislecel (VX-880) [7] [6] | Neutropenia (3 participants); Two deaths (cryptococcal meningitis; dementia progression) - deemed unrelated to product. | Yes, lifelong | Risks associated with chronic immunosuppression (infection, malignancy); Hepatic portal vein infusion challenges. |

| Stem Cell-Derived Islets (Vertex) [21] | Data not fully published for entire cohort. | Yes | Trade-off between insulin dependence and lifelong immunosuppression. |

| Hybrid Immune System (Stanford) [14] | No graft-versus-host disease reported in preclinical models. | No | Preclinical stage; Logistical challenge of sourcing matched blood stem cells and islets from the same donor. |

| PEC-01 in Encapsulation Device [21] | Foreign body response; pericapsular fibrosis limiting efficacy. | Varies (Open device requires it) | Inconsistent cell survival due to hypoxia; device encapsulation limits nutrient exchange. |

A primary differentiator among therapies is the requirement for chronic immunosuppression. While current clinical frontrunners like zimislecel require it, leading to significant adverse events [7] [6], next-generation approaches are actively engineering solutions to this hurdle, such as hypoimmune gene editing and the immune reset strategy [14] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The development of these therapies relies on a sophisticated toolkit of biological reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Stem Cell-Derived Beta Cell Therapy

| Reagent / Material Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in R&D |

|---|---|---|

| Signaling Molecules & Differentiation Factors | Activin A, Wnt3a, FGF10, Retinoic Acid, KAAD-cyclopamine, T3 (Thyroid Hormone), ALK5 Inhibitors [21] [2] | To direct pluripotent stem cells through sequential stages of pancreatic development, mimicking in vivo embryogenesis. |

| Cell Lines | Human Embryonic Stem Cells (hESCs), Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (hiPSCs) [21] [2] | Serve as the starting source material for generating insulin-producing cells. hiPSCs enable autologous approaches. |

| Immunosuppressive Agents | Glucocorticoid-free regimens (e.g., ATG, MMF) [7] [2] | To prevent allograft rejection in non-autologous transplantation protocols during clinical trials. |

| Encapsulation Device Materials | Semi-permeable macroencapsulation membranes (e.g., ViaCyte's devices) [21] | To physically shield transplanted cells from immune attack, potentially obviating the need for systemic immunosuppression. |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 for creating "hypoimmune" cells (e.g., B2M−/−, CIITA−/−, HLA-E+ expression) [6] | To genetically modify stem cells to evade host immune detection, a promising strategy to eliminate immunosuppression. |

The collective evidence from early-phase trials marks a turning point, demonstrating that restored islet function and insulin independence are achievable clinical outcomes in T1D. The leading candidate, zimislecel, has set a new benchmark for efficacy [7]. However, the future landscape will likely be defined by strategies that address the dual challenge of cell replacement and autoimmunity without lifelong immunosuppression. The most promising avenues include hypoimmune gene-edited islets [6] and combined blood stem cell and islet transplants that induce immune tolerance [14]. For researchers, the immediate focus should be on refining differentiation protocols for full functional maturity, developing scalable and safe delivery platforms, and validating the long-term stability and safety of these curative approaches in diverse patient populations.

Clinical Translation: Delivery Methods, Immunosuppression, and Trial Designs

Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) results from the autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing pancreatic beta cells, leaving patients dependent on lifelong exogenous insulin therapy [1] [22]. While insulin management is the standard of care, it carries inherent risks of hypoglycemia and often fails to prevent long-term complications. Advanced cell therapies, particularly those utilizing stem-cell-derived beta cells, aim to address the underlying pathophysiology by restoring the body's ability to produce and regulate insulin physiologically [1]. The two dominant technological paradigms for delivering these curative cells are infused cell products and encapsulated cell devices. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these platforms, focusing on their operational principles, efficacy data, manufacturing considerations, and translational challenges, providing a objective resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Infused Cell Products

Infused cell therapies involve the direct administration of stem-cell-derived pancreatic islet cells into a patient's portal vein [22]. Once infused, these cells, such as the allogeneic product Zimislecel, engraft within the liver and begin to function as endogenous islets, secreting insulin in a glucose-responsive manner [7] [22]. This platform requires the recipient to be on a chronic immunosuppressive regimen to protect the engrafted cells from host immune rejection and to prevent the recurrence of autoimmunity [22] [23]. The mechanism of action is therefore direct cell replacement and functional integration into the host's metabolic system.

Encapsulated Cell Products

Encapsulated cell therapies co-house therapeutic doses of cells within semipermeable biomaterial devices, which are then implanted into sites such as the subcutaneous space [24]. These encapsulation devices are designed to act as immunoprotective barriers, allowing for the bidirectional diffusion of oxygen, nutrients, and therapeutic proteins like insulin, while simultaneously excluding hostile immune cells and antibodies [24]. The primary mechanism is the creation of a bio-hybrid organ that provides continuous, glucose-responsive insulin secretion without mandating systemic immunosuppression, as the membrane protects the cells from immune attack.

Table: Comparative Mechanism of Action and Technology Features

| Feature | Infused Products (e.g., Zimislecel) | Encapsulated Products |

|---|---|---|

| Delivery Method | Infusion into the hepatic portal vein [22] | Implantation of macrodevices (e.g., subcutaneous) [24] |

| Immunoprotection | Systemic immunosuppression [22] [23] | Device-based, via semipermeable membranes [24] |

| Proposed MOA | Direct engraftment and functional integration into host liver [7] | Function as an external, bio-hybrid organ secreting insulin [24] |

| Key Cell Source | Allogeneic stem-cell-derived, fully differentiated islets [7] [22] | Allogeneic cells or xenogeneic islets [24] |

Comparative Efficacy and Safety Data

Clinical Performance of Infused Cell Therapy

Recent Phase 1/2 trial results for Zimislecel demonstrate the substantial therapeutic potential of the infused platform. In a cohort of 12 T1D patients with impaired hypoglycemic awareness who received a full dose:

- Glycemic Control: All 12 participants achieved an HbA1c level of below 7%, with the mean HbA1c decreasing from 7.8% to 6.0% [23]. The mean Time-in-Range (TIR) on continuous glucose monitoring exceeded 93% [23].

- Insulin Independence: 83% (10 out of 12) of participants were free from exogenous insulin use at the 12-month mark [7] [22] [23].

- Hypoglycemia: Severe Hypoglycemic Events (SHEs) were eliminated from day 90 onwards [22] [23].

- Safety: The therapy was generally well-tolerated. The safety profile was consistent with the expected effects of the steroid-free immunosuppressive regimen and the infusion procedure itself. Two deaths occurred in the broader trial program but were assessed as unrelated to the cell therapy [7] [22].

Pre-clinical and Development-Stage Data for Encapsulated Therapies

Encapsulated cell therapies are largely in pre-clinical and early clinical development. Their efficacy is highly contingent on overcoming the foreign body response (FBR) and ensuring adequate oxygen and nutrient transport to the encapsulated cells [24].

- Material Science Advances: Studies using TMTD-modified alginate for microencapsulation have shown promise. In mouse models of diabetes, xenogeneic stem-cell-derived islets encapsulated in TMTD-alginate achieved diabetic reversal for over 170 days [24]. This approach has been successfully scaled to non-human primates, supporting islet survival and function for four months without immunosuppression [24].

- Key Challenge: A major hurdle is hypoxia within macrodevices, which can lead to significant cell death. Achieving therapeutic cell densities (e.g., ~10,000 islet equivalents/cm²) in a patient-friendly device size remains a significant materials and engineering challenge [24].

Table: Summary of Key Efficacy and Safety Outcomes

| Parameter | Infused Product (Zimislecel) | Encapsulated Products (Pre-clinical) |

|---|---|---|

| HbA1c Reduction | Mean reduction from 7.8% to 6.0% [23] | Demonstrated functional efficacy in animal models [24] |

| Insulin Independence | 83% (10/12) at 12 months [7] [23] | The primary goal; achieved in rodent models [24] |

| Severe Hypoglycemia | Eliminated [22] [23] | Not specifically reported |

| Key Safety Concern | Risks associated with chronic immunosuppression and infusion procedure [7] [22] | Foreign body response, fibrotic encapsulation, and hypoxia [24] |

| Immunosuppression | Required [22] [23] | Not required (Device-dependent) [24] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Infused Cell Therapy Clinical Trials

The evaluation of Zimislecel follows a structured clinical trial protocol, as seen in the FORWARD (VX-880-101) study [7] [22].

- Patient Population: Adults with T1D, impaired hypoglycemic awareness, and a history of severe hypoglycemic events.

- Manufacturing: Zimislecel is manufactured as an allogeneic, stem-cell-derived, fully differentiated islet cell product.

- Dosing: A single infusion of a full dose (0.8 × 10^9 cells) is delivered into the hepatic portal vein [7].

- Immunosuppression: Patients receive a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen, typically including induction and maintenance agents, to prevent rejection [7] [22].

- Endpoints:

- Functional Assessment: Engraftment and islet function are confirmed through a 4-hour Mixed-Meal Tolerance Test (MMTT) with serial measurement of C-peptide, which is undetectable at baseline in these patients [7].

Protocol for Assessing Encapsulated Device Performance

Pre-clinical assessment of encapsulated therapies focuses on material biocompatibility and in vivo function [24].

- Material Fabrication & Screening:

- Hundreds of alginate analogs are synthesized through combinatorial chemistry (e.g., modifying with triazole-thiomorpholine dioxide (TMTD)) [24].

- These materials are screened in vivo, typically in the subcutaneous space of immune-competent mice (e.g., C57BL/6 J), to identify leads that minimize fibrotic encapsulation.

- Device Implantation and Efficacy Testing:

- Lead materials are used to encapsulate stem-cell-derived islets or insulinoma cells.

- Devices are implanted into streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rodent models.

- Primary Endpoint: Reversal of diabetes, defined as the restoration of normoglycemia without exogenous insulin support.

- Secondary Endpoints: Measurement of human C-peptide in blood (for xenografts), explant histology to assess fibrosis and cell survival, and immunohistochemical analysis for markers of immune response and vascularization [24].

- Advanced Testing: Promising devices are advanced into larger animal models, such as non-human primates, to validate efficacy and biocompatibility in a physiology more relevant to humans [24].

Key Challenges and Translational Considerations

The development paths for infused and encapsulated therapies are marked by distinct challenges.

Challenges for Infused Products

- Chronic Immunosuppression: The necessity for lifelong immunosuppression exposes patients to increased risks of infection, potential organ toxicity, and other drug-related side effects [22] [25].

- Limited Cell Supply: Manufacturing a consistent and scalable supply of fully functional, stem-cell-derived islets is complex and costly.

- Durability and Rejection: The long-term durability of the graft is not yet fully established, and the potential for immune rejection or autoimmune recurrence remains a persistent risk [25].

Challenges for Encapsulated Products

- The Foreign Body Response (FBR): This is the primary barrier. The FBR leads to the formation of a dense, collagenous fibrotic capsule around the implant, which blocks the transport of oxygen and nutrients, leading to hypoxia and cell death [24].

- Hypoxia: High cell packing densities required for a therapeutic effect in a reasonably sized device can create extreme hypoxic cores, necessitating advanced materials or integrated oxygenation solutions [24].

- Material Design and Durability: Creating membranes with precise pore sizes for optimal immunoprotection, while maintaining robust mechanical properties for long-term implantation, is a significant materials science challenge.

Diagram: Key Workflows and Challenges for Cell Therapy Platforms. The infused platform's primary challenge is the need for systemic immunosuppression (red), while the encapsulated platform's key challenge is the Foreign Body Response leading to fibrosis and hypoxia (red).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development of these advanced therapies relies on a suite of specialized reagents, materials, and assays.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Beta Cell Therapy Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Stem-Cell-Derived Islets | The foundational therapeutic agent for both platforms; insulin-producing, glucose-responsive cells. | Differentiated from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) for infusion or encapsulation [1]. |

| TMTD-Modified Alginate | A lead biomaterial for microencapsulation that demonstrates reduced fibrotic encapsulation in vivo. | Used to form hydrogel capsules around islets for immunoprotection without immunosuppression [24]. |

| Zwitterionic Polymers (e.g., PCBMA) | Surface modification materials that resist protein fouling and reduce the Foreign Body Response. | Coating macroencapsulation devices to improve biocompatibility and reduce fibrosis [24]. |

| Mixed-Meal Tolerance Test (MMTT) | A key bioassay to assess the dynamic insulin secretion and functional engraftment of the transplanted cells. | Measuring C-peptide levels in patients post-infusion to confirm graft function [7] [1]. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) | A wearable technology providing real-time, ambulatory glycemic data for efficacy assessment. | Used in clinical trials to calculate Time-in-Range and assess hypoglycemia risk [23]. |

| Steroid-Free Immunosuppressive Regimen | A drug combination to prevent allograft rejection without the beta-cell-toxic effects of steroids. | Administered to patients receiving infused islet products like Zimislecel [7] [22]. |

The pursuit of a functional cure for T1D is being aggressively advanced through two complementary technological paradigms: infused and encapsulated stem-cell-derived beta cell therapies. Infused products, exemplified by Zimislecel, have demonstrated compelling clinical proof-of-concept, achieving insulin independence and normoglycemia in a majority of patients in early trials, albeit with the trade-off of requiring chronic immunosuppression [7] [22] [23]. In contrast, encapsulated products offer the potential for an off-the-shelf, immunosuppression-free therapy but must overcome significant translational barriers related to the host foreign body response and device-induced hypoxia [24].

Future progress will be driven by parallel advancements. For infused therapies, the focus will be on optimizing immunosuppression regimens, validating long-term durability, and scaling manufacturing. For encapsulated therapies, the critical path forward lies in fundamental materials science—developing "superbiocompatible" materials that completely evade the FBR and engineering devices that ensure adequate oxygen supply to the encapsulated cells. As both platforms evolve, they hold the collective promise of resetting the standard of care for T1D from lifelong management to a definitive, curative treatment.

For individuals with type 1 diabetes (T1D), allogeneic beta-cell replacement represents a promising path toward restoring endogenous insulin production. The recent development of stem cell-derived islets (SC-islets) provides a potentially unlimited source of insulin-producing cells, overcoming the critical limitation of donor scarcity inherent to cadaveric islet transplantation [4]. However, the success of these revolutionary therapies is entirely dependent on effective immunosuppression protocols to protect the graft from the host immune system. Without such protection, allogeneic cells are rapidly rejected, negating any therapeutic benefit. This guide compares the current landscape of immunosuppressive strategies, from conventional pharmaceutical regimens to groundbreaking genetic and cellular approaches, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed analysis of their mechanisms, efficacy, and trade-offs.

Conventional Immunosuppression in Clinical Practice

Conventional immunosuppression relies on a combination of drugs that systemically dampen the immune response to prevent graft rejection. These protocols are the current clinical standard for both solid organ and cellular transplants, including the emerging class of stem cell-derived islet products.

Key Agents and Regimens

The glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen used in a recent phase 1-2 trial of stem cell-derived islets (zimislecel) exemplifies a modern approach [7]. The trial demonstrated that this protocol could support engraftment and function, with 10 out of 12 participants achieving insulin independence at one year. However, the serious adverse events observed, including one death from cryptococcal meningitis, underscore the significant risks of systemic immunosuppression, such as increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections [7].

The selection and management of these drugs are critical. A 2025 retrospective study of patients receiving post-transplantation cyclophosphamide (PTCy) for GVHD prophylaxis found that tacrolimus or sirolimus levels ≥10 ng/mL in the first week post-transplant were associated with decreased overall survival, suggesting that lower target levels may be optimal with PTCy-based regimens [26].

Table 1: Common Immunosuppressive Agents and Their Roles in Allogeneic Graft Protection

| Agent Class | Example Drugs | Primary Mechanism of Action | Common Clinical Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcineurin Inhibitors (CNI) | Tacrolimus, Cyclosporine | Inhibits T-cell activation by blocking IL-2 production | Foundation of most maintenance regimens [26] |

| Antiproliferatives | Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF) | Inhibits lymphocyte proliferation by blocking purine synthesis | Used in combination with CNIs [26] [27] |

| mTOR Inhibitors | Sirolimus | Blocks cytokine-driven T-cell proliferation | Alternative to CNIs; part of PTCy regimens [26] |

| Biologics | Anti-thymocyte Globulin (ATG) | Depletes T-cells | Induction therapy; part of tolerance protocols [28] |

| Alkylating Agents | Cyclophosphamide (PTCy) | Eliminates alloreactive T-cells post-transplant | GVHD prophylaxis in haploidentical HCT [26] [29] |

Emerging Paradigms: Engineering Immune Evasion

To circumvent the complications of lifelong drug-based immunosuppression, significant research is focused on engineering the graft itself to evade immune detection. These "hypoimmune" strategies aim to create "off-the-shelf" cell products that do not require recipient immunosuppression.

Hypoimmunogenic Engineering of Stem Cell-Derived Islets

The core principle of hypoimmunogenic engineering is to genetically modify the donor cells to reduce their immunogenicity. This primarily involves editing the expression of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules, which are the primary triggers of T-cell-mediated rejection.

- HLA Class I Deletion: Knocking out Beta-2-microglobulin (B2M) eliminates surface expression of HLA class I molecules, preventing recognition by host CD8+ T-cells [30] [6].

- Preventing NK Cell Attack: The deletion of HLA class I can trigger "missing-self" recognition and attack by natural killer (NK) cells. To counter this, strategies often include the overexpression of non-classical HLA molecules (e.g., HLA-E, HLA-G) that engage inhibitory receptors on NK cells [30] [6].

- Modulating Co-Inhibitory Signals: Overexpression of immunomodulatory ligands like PD-L1 (Programmed Death-Ligand 1) on the graft surface can engage PD-1 on host T cells, directly inducing T-cell exhaustion and tolerance [30] [6].

- CD47 Overexpression: The "don't eat me" signal provided by CD47 helps protect graft cells from phagocytosis by host macrophages [30].

A 2025 review highlighted that combining these approaches—for instance, creating B2M−/− CIITA−/− PSCs with engineered expression of HLA-G, PD-L1, and CD47—can simultaneously protect against T-cell and NK-cell-mediated rejection, creating a robustly hypoimmunogenic graft [6].

The following diagram illustrates the key genetic modifications involved in creating a hypoimmunogenic stem cell-derived islet and how they interact with the host immune system.

A Paradigm Shift: Immune System Reset and Hybrid Tolerance

Perhaps the most transformative approach is moving from suppressing or evading the immune system to fundamentally reprogramming it. This strategy, exemplified by recent work at Stanford Medicine, involves creating a "hybrid" immune system that tolerates the graft.

Protocol for Immune System Reset in Autoimmune Diabetes

This protocol combines a gentle conditioning regimen with the transplantation of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and pancreatic islets from the same donor [14]. The goal is to establish a state of mixed chimerism, where the host's immune system is partially repopulated by donor-derived immune cells, leading to mutual tolerance.

- Step 1: Gentle Conditioning: The recipient is pre-treated with a regimen of immune-targeting antibodies, low-dose radiation, and a drug used for autoimmune diseases. Unlike the myeloablative conditioning used in oncology, this "gentle" approach is designed not to eradicate the host immune system but to create a niche for donor cell engraftment [14].

- Step 2: Combined Transplant: The recipient receives an infusion of donor-derived HSCs alongside pancreatic islets. The HSCs are the key to tolerance induction.

- Step 3: Establishment of a Hybrid Immune System: The donor HSCs engraft and give rise to immune cells that coexist with the recipient's immune cells. This hybrid system "re-educates" the immune system to recognize the donor islets as "self," halting the underlying autoimmune attack on beta cells and preventing rejection of the transplanted islets [14].

In a mouse model of T1D, this approach completely prevented or cured diabetes in all animals without the use of immunosuppressive drugs and without causing graft-versus-host disease [14]. The translational potential is high, as the core components of this protocol are already used in clinical practice for other conditions.

The workflow below outlines the key steps in this innovative protocol for achieving graft tolerance through an immune system reset.

Comparative Analysis of Immunosuppression Protocols

The choice of an immunosuppression strategy involves balancing efficacy, safety, complexity, and scalability. The table below provides a direct comparison of the three main paradigms.

Table 2: Comparison of Immunosuppression Protocols for Allogeneic Grafts

| Parameter | Conventional Pharmacotherapy | Hypoimmunogenic Grafts | Immune System Reset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Systemic inhibition of immune cell function | Reduction of graft immunogenicity via genetic engineering | Establishment of donor-specific central tolerance |

| Graft Source | Any (Cadaveric islets, SC-islets) | Genetically engineered SC-islets only | Requires HSCs and islets from same donor |

| Immunosuppression Duration | Lifelong (chronic) | Potentially none | Transient (during conditioning) |

| Key Risks | Opportunistic infections, malignancy, drug toxicity [7] | Potential for immune escape, tumorigenicity from edits [30] | Graft-versus-host disease, conditioning toxicity [28] |

| Efficacy Evidence | Insulin independence in 83% at 1 year (Zimislecel trial) [7] | Preclinical NHP studies; early-phase human trials [30] [6] | Cured T1D in mouse models; human kidney transplant success [14] [28] |

| Scalability | High, but limited by drug cost/toxicity | Theoretically high for "off-the-shelf" products | Limited by donor availability & procedural complexity |

| Stage of Development | Clinical standard of care | Early-phase clinical trials | Preclinical/early clinical investigation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Research into these advanced immunosuppression protocols relies on a suite of critical reagents and tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Graft Immunosuppression

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Gene editing for creating knock-out (e.g., B2M, CIITA) and knock-in (e.g., CD47, HLA-G) mutations in pluripotent stem cells. | Generating hypoimmunogenic stem cell lines for differentiation into SC-islets [30] [6]. |

| Anti-Thymocyte Globulin (ATG) | Polyclonal antibody used for in vivo T-cell depletion in animal models. | Mimicking the lymphodepleting conditioning regimen used in immune reset protocols [28]. |

| Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide (PTCy) | Alkylating agent administered after transplant to eliminate alloreactive T-cells. | Studying GVHD prophylaxis in humanized mouse models of combined HSC/islet transplantation [26] [29]. |

| Tacrolimus / Sirolimus | Pharmacologic inhibitors of T-cell activation and proliferation. | Establishing therapeutic drug level targets in preclinical transplant models and clinical trials [26] [7]. |

| Flow Cytometry Panels (Immune Cell Subsets) | High-dimensional profiling of immune cell populations (T, B, NK cells, monocytes) post-transplant. | Monitoring immune reconstitution, chimerism, and rejection responses [27]. |

The field of immunosuppression for allogeneic grafts is undergoing a rapid evolution, driven by the pressing need to make curative cell therapies for T1D both effective and safe. While conventional pharmacotherapy remains a proven, if imperfect, cornerstone, the future is leaning towards more integrated solutions. The development of hypoimmunogenic SC-islets addresses the problem at the source of immune recognition, while the immune reset strategy seeks to create a lasting state of tolerance. Each approach presents a distinct profile of advantages, risks, and developmental challenges. For researchers and drug developers, the path forward will likely involve combining elements from these strategies—for example, using a gentler conditioning regimen to support the engraftment of a partially hypoimmunogenic graft—to achieve the ultimate goal: a durable, functional cure for T1D without the burden of lifelong immunosuppression.

Clinical trials are the cornerstone of therapeutic development, providing the critical evidence required for regulatory approval and clinical adoption. For innovative therapies like stem cell-derived beta cells for Type 1 Diabetes (T1D), optimal trial design is paramount for accurately demonstrating safety and efficacy. The traditional clinical trial paradigm is undergoing significant modernization, moving away from rigid, historically-based designs toward more flexible, patient-centric, and data-driven approaches [31]. This evolution encompasses all trial elements: from how doses are selected and optimized, to how patients are chosen for participation, and what endpoints are measured to determine success. These changes are particularly relevant for complex cellular therapies targeting T1D, where the therapeutic mechanism differs fundamentally from conventional small molecules or biologics. This article examines the core components of modern trial design—dosing strategies, patient selection, and endpoint selection—within the context of T1D research, providing a framework for developing robust clinical programs for stem cell-derived beta cell therapies.

Dosing Strategies: From Maximum Tolerated Dose to Therapeutic Optimization

Dosing strategy is a foundational element that can determine the ultimate success or failure of a drug development program. The traditional approach, developed for cytotoxic chemotherapies, focuses on identifying the Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD). This method, often using a "3+3" trial design, escalates doses in small patient cohorts until a pre-defined level of dose-limiting toxicity is observed [31]. However, for many modern therapeutics, including targeted agents and potentially cellular therapies, the MTD paradigm is often suboptimal. Studies show that nearly 50% of patients in late-stage trials of targeted therapies require dose reductions due to intolerable side effects, and the FDA has required post-marketing dose-finding studies for over 50% of recently approved cancer drugs [31]. This demonstrates the inadequacy of relying solely on short-term toxicity data to establish a dosage for long-term use.

Modern Dose Optimization Frameworks

Recognizing these limitations, regulatory agencies have championed new frameworks. The FDA's Project Optimus encourages a shift from MTD to a focus on identifying doses that optimize the balance between efficacy and safety [31] [32]. This involves directly comparing multiple dosages in trials designed to assess antitumor activity, safety, and tolerability. Key modern dose-finding approaches include:

- Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD): Utilizing mathematical models that incorporate pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and biomarker data to predict effective dosing in humans from preclinical data, often allowing for higher, more effective starting doses than traditional methods [31].

- Novel Trial Designs: Adaptive trial designs, such as the Bayesian Optimal Interval (BOIN) design, allow for more nuanced dose-escalation and de-escalation based on both efficacy and safety outcomes from preceding patient cohorts. These designs can treat more patients at potentially optimal dose levels and adapt based on accumulating data [32].

- Biomarker-Driven Dosing: The concept of the Biologically Effective Dose (BED) is crucial for modern therapies. The BED is determined using biomarkers that indicate target engagement and biological activity, which may occur at a dose lower than the MTD [32]. For stem cell-derived beta cells, this could involve imaging biomarkers or secreted factors indicating engraftment and function.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional vs. Modern Dosing Paradigms in Oncology (as a model for other fields)

| Feature | Traditional MTD Paradigm | Modern Optimization Paradigm |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Identify maximum tolerated dose | Identify dose with optimal efficacy-safety balance |

| Key Trial Design | 3+3 dose escalation | Model-informed, adaptive designs (e.g., BOIN) |

| Data Driving Decisions | Short-term toxicity | Integrated safety, efficacy, and biomarker data |

| Role of Biomarkers | Limited | Central to establishing Biologically Effective Dose (BED) |

| Typical Outcome | Single MTD for development | Multiple doses compared for final selection |

| Post-Marketing Needs | Common (dose optimization often required) | Reduced (optimization occurs pre-approval) |

Source: Adapted from AACR Blog and FDA-AACR Workshop Summary [31] [32]

Application to Stem Cell-Derived Beta Cell Therapies

For a stem cell-derived beta cell therapy, the dosing strategy must be uniquely tailored. The therapy is not a simple drug with linear pharmacokinetics, but a living product. Dosing may be defined by the number of functional islet equivalents or cells transplanted, the transplantation procedure (e.g., single vs. multiple infusions), and the intensity of concomitant immunosuppression. A model-informed approach could use preclinical data on engraftment efficiency and function to model human dosing. An adaptive trial could then evaluate two or more cell doses, using biomarkers like circulating C-peptide or insulin independence to identify a BED, while meticulously monitoring safety signals related to the transplantation procedure and immunosuppression.

Patient Selection: Balancing Scientific Rigor with Inclusivity

Patient eligibility criteria define the study population and are essential for patient safety and data interpretability. However, excessively narrow criteria can hinder enrollment, delay trial completion, and limit the generalizability of the results to real-world patient populations [33] [34]. A meta-analysis found that 22% of potential trial participants were excluded due to restrictive eligibility criteria, a significant barrier to accrual [34].

Expanding Eligibility Criteria

A major initiative in clinical trial modernization is the expansion of eligibility criteria to be more inclusive, while maintaining scientific integrity and patient safety. Joint recommendations from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and Friends of Cancer Research provide a framework for broadening eligibility in key areas [33]:

- Brain Metastases: Allowing patients with stable, treated brain metastases.

- HIV/AIDS: Including patients with well-controlled HIV infection.

- Prior and Concurrent Malignancies: Enrolling patients with a history of other cancers, based on individualized risk assessment.

- Organ Dysfunction: Carefully including patients with mild to moderate renal, hepatic, or cardiac dysfunction, rather than using absolute laboratory cut-offs.

- Age: Including adolescent patients in adult trials where scientifically appropriate.

Implementing these expanded criteria in protocol templates has successfully increased the inclusiveness of trials without compromising safety [33].

Leveraging Real-World Data for Smarter Enrollment

Real-World Data (RWD), such as electronic health records (EHR) and insurance claims data, are powerful tools for designing more feasible and representative trials [35]. RWD can be applied in two key ways:

- Planning Feasible Eligibility Criteria: By analyzing RWD from large patient populations, sponsors can simulate the impact of different eligibility criteria on the potential pool of participants. This allows for the design of criteria that are broad enough for efficient recruitment but narrow enough to address the scientific question [35].

- Enhancing Recruitment: RWD can be used to identify potential participants more efficiently through direct outreach or by flagging eligible patients at the point of care, a strategy shown to improve recruitment effectiveness and efficiency [35].

Table 2: Using Real-World Data (RWD) for Patient Selection and Recruitment

| RWD Application | Description | Utility in Stem Cell-Derived Beta Cell Trials |

|---|---|---|

| EHR Data Analysis | Analyzing de-identified electronic health records to understand patient demographics, comorbidities, and treatment patterns. | Estimate the real-world population of T1D patients who would meet proposed trial criteria; identify centers with high volumes of eligible patients. |

| Claims Data Analysis | Using insurance claims to track disease codes, procedures, and medication use across healthcare systems. | Understand healthcare utilization patterns of T1D patients to design feasible visit schedules and endpoint assessments. |

| Site Identification | Using RWD to identify clinical sites with a high concentration of the target patient population. | Select high-performing clinical trial sites with access to the precise T1D patient profile needed for the study. |

| Patient Pre-screening | Using RWD platforms to identify potentially eligible patients for targeted outreach, with appropriate privacy safeguards. | Accelerate enrollment by pre-identifying patients who meet key lab or diagnostic criteria for T1D with complications. |

Source: Adapted from CTTI Recommendations on RWD [35]

For a trial of stem cell-derived beta cells, eligibility must be carefully considered. Key inclusion criteria would likely involve a confirmed diagnosis of T1D with specific autoantibodies, a disease duration range, and demonstrated C-peptide deficiency. Using RWD, sponsors could model whether adding common exclusions—such as a history of other autoimmune diseases, body mass index (BMI) limits, or specific comorbid conditions—would drastically reduce the recruitable population. The goal is to justify each criterion scientifically rather than relying on historical precedent, thereby ensuring the trial can enroll a population that is both representative and adequate to answer the research question.

Primary Endpoints: Defining and Measuring Success

The primary endpoint is the ultimate measure of a trial's success. It must be precisely defined, clinically meaningful, and reliably measurable. The choice of endpoint is dictated by the phase of the trial, the mechanism of action of the therapy, and regulatory standards.

Established Endpoints in Diabetes Trials

In T1D and related metabolic disease trials, several well-validated endpoints are commonly used:

- Glycated Hemoglobin (HbA1c): A measure of average blood glucose over the preceding 2-3 months. It is a standard primary endpoint for many glucose-lowering therapies, as seen in the SEPRA trial for semaglutide, where the proportion of participants achieving HbA1c <7.0% was the primary outcome [36].