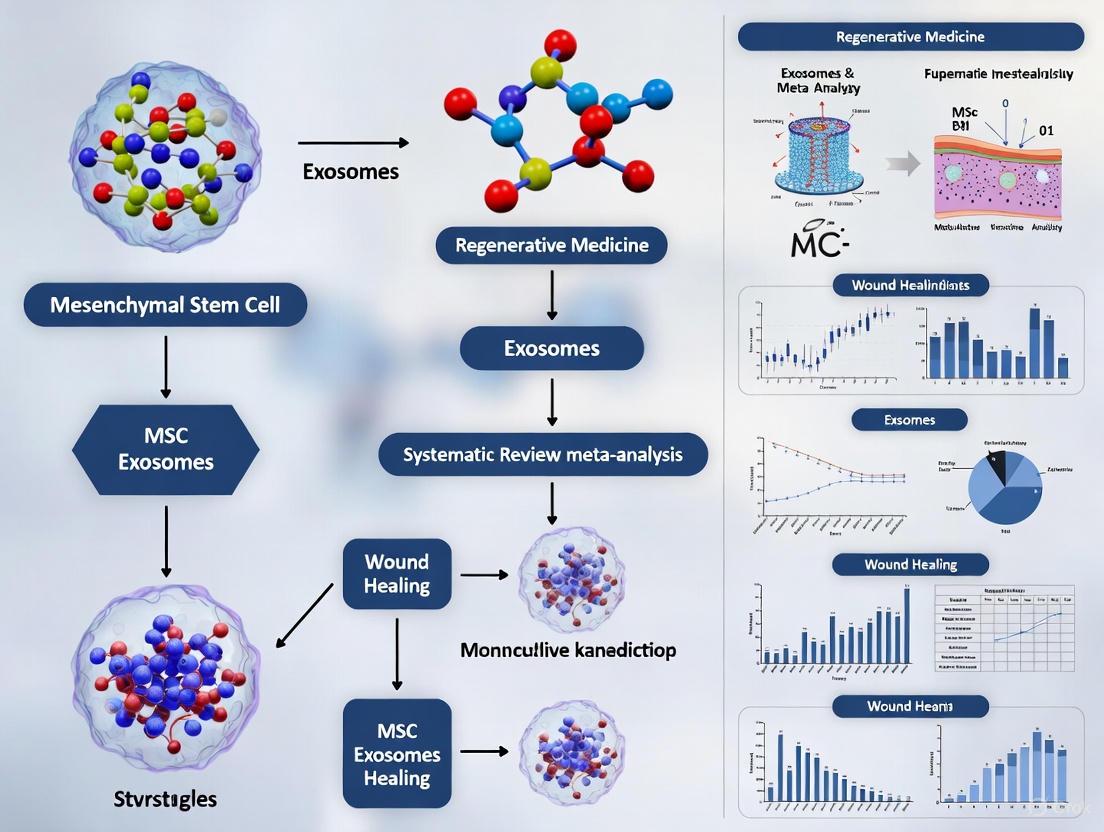

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of MSC Exosomes in Wound Healing: Mechanisms, Efficacy, and Clinical Translation

This systematic review and meta-analysis synthesizes current preclinical and clinical evidence on mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exosomes) for wound healing.

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of MSC Exosomes in Wound Healing: Mechanisms, Efficacy, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This systematic review and meta-analysis synthesizes current preclinical and clinical evidence on mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exosomes) for wound healing. We examine the foundational biological mechanisms through which MSC-exosomes modulate inflammation, promote angiogenesis, and enhance tissue regeneration across various wound models, including diabetic, radiation-induced, and chronic wounds. The analysis explores methodological considerations for exosome isolation, characterization, and therapeutic application, alongside optimization strategies such as engineering and biomaterial integration. By critically evaluating comparative efficacy between MSC sources and validation through clinical trials, we address the translational challenges and future directions for developing MSC-exosome therapies as a promising cell-free treatment paradigm for enhanced wound management.

Unraveling the Mechanisms: How MSC Exosomes Orchestrate Wound Repair

Exosomes are a heterogeneous subpopulation of extracellular vesicles, typically 30–150 nm in diameter, that originate from the endosomal system and are released upon the fusion of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) with the plasma membrane [1] [2]. Since their initial description in the 1980s, exosomes have been recognized not as mere cellular waste bags but as potent mediators of intercellular communication, shuttling functional cargo—including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—between cells [2] [3]. This role is particularly critical in the proposed therapeutic application of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) for wound healing, where they modulate inflammation, promote angiogenesis, and stimulate tissue regeneration through their paracrine activity [4] [5] [6]. The efficacy of these exosomes is fundamentally governed by their molecular composition, which is determined during biogenesis by the machinery responsible for cargo sorting and ILV formation [2] [7].

The process of exosome generation is primarily governed by two overarching, and sometimes overlapping, mechanisms: the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)-dependent pathway and various ESCRT-independent pathways [1] [3] [7]. Understanding the nuances of these pathways is essential for researchers aiming to harness MSC-Exos for therapeutic purposes, as the specific loading of cargo directly influences their functional impact on recipient cells in the wound microenvironment [2] [6]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these biogenesis pathways, detailing their mechanisms, key cargo, and experimental approaches for their study.

Core Machinery of Exosome Biogenesis

The biogenesis of exosomes is an intricate process that begins with the formation of early endosomes from the plasma membrane. During their maturation into late endosomes, the inward budding of the endosomal limiting membrane generates intraluminal vesicles (ILVs), transforming the structure into a multivesicular body (MVB) [1] [8]. The MVB represents a critical branch point in cellular trafficking; it can either fuse with lysosomes for degradation of its contents or fuse with the plasma membrane to release the ILVs into the extracellular space as exosomes [3] [7]. The molecular machinery that drives ILV formation and cargo selection is classified into two main categories.

The ESCRT-Dependent Pathway

The ESCRT machinery is a well-characterized, ubiquitin-dependent system comprising four protein complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, and -III) that operate in concert with accessory proteins like VPS4 and Alix [1] [3]. The process is highly coordinated, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: The Sequential Action of the ESCRT Complex in Exosome Biogenesis

| ESCRT Complex | Key Components | Primary Function in Cargo Sorting and ILV Formation |

|---|---|---|

| ESCRT-0 | HRS, STAM | Recognizes and clusters ubiquitinated cargo on the endosomal membrane; initiates pathway recruitment [1] [3]. |

| ESCRT-I & II | TSG101, VPS28 | Recruited by ESCRT-0; work together to deform the endosomal membrane, initiating bud formation [1] [2]. |

| ESCRT-III | CHMP4, CHMP3 | Forms filaments that constrict the neck of the budding vesicle, leading to membrane scission and ILV release [1] [3]. |

| Accessory Proteins | VPS4, Alix | VPS4 recycles the ESCRT machinery using ATP; Alix can provide an alternative ESCRT-III recruitment [1] [3]. |

This pathway is particularly important for sorting ubiquitinated proteins, such as endocytosed growth factor receptors [2]. Furthermore, non-canonical ESCRT-dependent pathways exist. For instance, the Syndecan-Syntenin-Alix axis sorts certain cargoes (e.g., fibroblast growth factor receptor) in a ubiquitin-independent manner. In this pathway, the transmembrane proteoglycan syndecan binds the adaptor protein syntenin, which then recruits Alix to nucleate ESCRT-III assembly and facilitate ILV formation [3].

ESCRT-Independent Pathways

Despite the central role of ESCRT, exosomes can still form upon ESCRT depletion, leading to the discovery of several ESCRT-independent mechanisms [1] [3]. These pathways often rely on the lipid composition of the endosomal membrane.

- The nSMase2-Ceramide Pathway: The enzyme neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2) hydrolyzes sphingomyelin to generate ceramide [3]. Ceramide molecules, with their conical structure, can spontaneously induce membrane curvature and facilitate the budding of ILVs. This pathway is crucial for the sorting of specific cargoes like the proteolipid protein (PLP) in oligodendrocytes and certain RNAs in cancer cells [1] [3]. The inhibitor GW4869 is commonly used to block this pathway [3].

- Tetraspanin-Enriched Microdomains: Tetraspanins (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81) are highly enriched in exosomes and organize membrane microdomains that facilitate the selective concentration of specific client proteins, such as β-catenin and metalloproteinases [1] [2]. For example, CD63 is involved in sorting melanosomal proteins in melanoma cells [1].

- Other Mechanisms: Additional factors contributing to ESCRT-independent biogenesis include lipid raft components (e.g., flotillins, caveolins) and the small GTPase ARF6 with its effector PLD2, which can promote ILV formation [1] [3].

Table 2: Comparative Overview of Key Exosome Biogenesis Pathways

| Feature | ESCRT-Dependent Pathway | nSMase2-Ceramide Pathway | Tetraspanin-Dependent Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Initiator | Ubiquitinated cargo / ESCRT-0 [1] [3] | Neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2) [3] | Tetraspanin web (e.g., CD63, CD81) [1] |

| Core Machinery | ESCRT-I, -II, -III, VPS4 [2] [3] | Ceramide [3] | Tetraspanins, associated proteins [1] |

| Model Cargo | Ubiquitinated receptors (e.g., EGFR) [2] | Proteolipid Protein (PLP) [1] [3] | Melanosomal protein (Pmel17) [1] |

| Common Inhibitors | siRNA targeting ESCRT components (e.g., TSG101) [3] | GW4869 [3] | siRNA targeting specific tetraspanins [1] |

The following diagram illustrates the coordination of these primary pathways within the endosomal system during exosome biogenesis.

Experimental Analysis of Biogenesis Pathways

Deciphering the contribution of specific biogenesis pathways requires a combination of genetic, pharmacological, and biochemical approaches. A core methodology involves isolating exosomes after perturbing a pathway of interest and analyzing the resulting changes in vesicle quantity and composition.

Key Methodologies and Reagents

Standard protocols begin with the isolation of exosomes, often via ultracentrifugation, size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), or commercial kits, from cell culture supernatants or biological fluids [8]. The following table lists essential reagents and tools for probing biogenesis mechanisms.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Exosome Biogenesis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Application in Pathway Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| GW4869 | Pharmacological inhibitor of nSMase2 [3] | Inhibits the ceramide-dependent pathway; used to assess its role in cargo loading and exosome secretion. |

| siRNA/shRNA | Gene knockdown (e.g., TSG101, Alix, CD63) [3] | Silences specific components of ESCRT or tetraspanin pathways to evaluate their necessity for exosome generation. |

| VPS4 Dominant-Negative | ATPase-deficient mutant of VPS4 [3] | Blocks the disassembly of the ESCRT-III complex, thereby inhibiting the final stages of ESCRT-mediated ILV scission. |

| Antibodies for WB/IF | Detect markers (CD63, CD81, Alix, TSG101, Flotillin) [1] [8] | Characterize exosome isolates and assess the presence/absence of specific cargoes after pathway inhibition. |

| Ultracentrifugation | Isolation of exosomes via high g-force [5] [8] | Standard method for purifying exosomes from conditioned media or biological fluids for downstream analysis. |

| NTA (Nanoparticle Tracking) | Measure particle size and concentration [5] | Quantifies changes in exosome secretion levels after pharmacological or genetic perturbation. |

A typical experimental workflow to dissect these pathways is outlined below.

Illustrative Experimental Data from Wound Healing Research

Research on MSC-Exos for wound healing often characterizes the exosomes without always delineating the specific biogenesis pathway. However, the functional outcomes are direct consequences of the cargo loaded via these mechanisms. For instance, a study on umbilical cord MSC-Exos (hUCMSC-Exos) used ultracentrifugation for isolation and nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) and western blotting (CD63, CD81) for characterization [5]. The study demonstrated that these exosomes promoted the proliferation and migration of human skin fibroblasts (HSFs) and enhanced tube formation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in vitro. In a mouse model, they accelerated wound closure, which was associated with reduced inflammation and stimulated angiogenesis [5]. While this study did not mechanistically probe biogenesis, the pro-healing effects imply the selective packaging of specific miRNAs and proteins, likely governed by the pathways described above.

Implications for MSC Exosomes in Wound Healing

The biogenesis pathways are not merely structural mechanisms; they are fundamental regulatory checkpoints that determine the functional payload of MSC-Exos. The selective sorting of anti-inflammatory miRNAs (e.g., miR-146a, miR-223) or pro-angiogenic proteins (e.g., VEGF) into exosomes is a controlled process [6]. Dysregulation in these pathways could lead to the production of exosomes with diminished therapeutic efficacy. Therefore, a deep understanding of ESCRT-dependent and independent mechanisms provides a rational basis for engineering or preconditioning MSCs to enhance the loading of desired therapeutic molecules into exosomes, ultimately optimizing their potential for treating chronic wounds [2] [6]. Future research focused on actively modulating these pathways in MSCs will be a critical step toward developing potent and reliable exosome-based therapeutics for regenerative medicine.

Exosomes, a class of extracellular vesicles (EVs) with a diameter of 30–150 nm, have emerged as pivotal mediators of intercellular communication within the wound microenvironment [9] [10]. These lipid-bilayer enclosed vesicles are secreted by nearly all cell types and carry a diverse cargo of bioactive molecules, including microRNAs (miRNAs), proteins, and lipids, which reflect the physiological state of their parent cells [11] [6]. Upon delivery to recipient cells, these molecular players orchestrate complex biological processes essential for tissue repair, such as anti-inflammatory responses, angiogenesis, fibroblast proliferation, and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling [11] [12] [6]. In the context of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes, this cargo serves as an in-situ reservoir, providing tissue-specific signals on demand to accelerate wound healing [11]. This systematic analysis comprehensively compares the roles, mechanisms, and experimental evidence for these key molecular players in exosomal communication, providing a foundation for understanding their therapeutic potential in wound management.

Exosomal Biogenesis and Cargo Loading

Exosomes originate through the inward budding of the endosomal membrane, forming multivesicular bodies (MVBs) that subsequently fuse with the plasma membrane to release their contents into the extracellular space [9]. This biogenesis involves two primary pathways: the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)-dependent and ESCRT-independent pathways [11]. During this process, bioactive molecules are selectively packaged into the forming vesicles. Interestingly, cells selectively sort miRNAs into extracellular vesicles through mechanisms that remain partially characterized but are essential for their function [11]. Similarly, proteins and lipids are incorporated through specific sorting mechanisms that define the exosome's composition and functional properties [9]. The resulting exosomes are adorned with molecular markers (e.g., CD63, CD9, CD81) that reflect their origin and facilitate receptor-mediated recognition and cargo delivery to target cells via membrane fusion or endocytosis [11]. This precise cargo loading mechanism ensures that exosomes deliver specific signals to coordinate the wound healing process.

Table 1: Primary Exosome Isolation and Characterization Techniques

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultracentrifugation | Sequential centrifugation based on size/density | Gold standard; no reagent required | Time-consuming; may cause vesicle damage |

| Size-Based Chromatography | Size exclusion using porous matrix | High purity; preserves vesicle integrity | Limited scalability; sample dilution |

| Polymer-Based Precipitation | Reduced solubility via crowding agents | Simple protocol; high yield | Co-precipitation of contaminants |

| Immunoaffinity Capture | Antibody binding to surface markers | High specificity for subpopulations | High cost; dependent on marker expression |

MicroRNAs: Master Regulators of Gene Expression

Biogenesis and Mechanism of Action

MiRNAs are short non-coding RNAs (19–24 nucleotides) that regulate post-transcriptional gene expression through complementary binding to target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or mRNA degradation [11]. The biogenesis of miRNA begins with transcription of primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) from host genes, which undergo sequential processing by Drosha and Dicer enzymes to become mature miRNAs [11]. These mature miRNAs are incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), where they guide the complex to partially complementary sequences primarily in the 3' untranslated region (3' UTR) of target mRNAs [11]. During exosome biogenesis, miRNAs are selectively sorted into vesicles through mechanisms that may involve specific miRNA motifs and RNA-binding proteins [11]. This selective sorting enables the packaging of functionally coordinated miRNA networks that can simultaneously regulate multiple targets in recipient cells.

Key Exosomal miRNAs in Wound Healing

Table 2: Functionally Validated Exosomal miRNAs in Wound Healing

| miRNA | Exosome Source | Validated Target/Pathway | Primary Functions in Wound Healing |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-126 | Bone Marrow MSCs | Unknown | Increases tube formation; promotes angiogenesis [11] |

| miR-146a | MSCs | NF-κB signaling | Inhibits NF-κB; promotes M1 to M2 macrophage transition [6] |

| miR-223 | MSCs | NLRP3 inflammasome | Suppresses NLRP3 activation; reduces inflammation [6] |

| miR-21 | ADSCs | Unknown | Enhances fibroblast proliferation and migration [6] |

| miR-29a | ADSCs | Unknown | Promotes fibroblast activation; ECM remodeling [6] |

| miR-124a | Neuronal cells | GLT1 (glutamate transporter) | Regulates extracellular glutamate concentration [11] |

| let-7b | Preconditioned MSCs | Unknown | Enhances anti-inflammatory macrophage polarization [6] |

Exosomal miRNAs regulate all phases of wound healing through precise molecular interventions. During inflammation, miR-146a and miR-223 attenuate excessive inflammatory responses by targeting NF-κB signaling and NLRP3 inflammasome activation, respectively [6]. In the proliferative phase, miR-21 and miR-29a enhance fibroblast proliferation and migration, while miR-126 potently stimulates angiogenesis—a critical process for restoring blood supply to damaged tissue [11] [6]. Notably, a recent study identified 28 key miRNAs with significant pro-proliferation, anti-inflammatory, and anti-fibrosis functions that were encapsulated into synthetic exosome-like vesicles, demonstrating comparable efficacy to natural MSC exosomes in accelerating burn wound healing and reducing scarring [13]. This functional synergy among exosomal miRNAs enables coordinated regulation of the entire wound healing cascade.

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

The therapeutic potential of exosomal miRNAs has been validated through standardized experimental approaches. In vitro functional assays include CCK-8 assays for cell proliferation, transwell migration assays, tube formation assays for angiogenesis, and gel contraction assays for fibroblast function [13]. For example, exosomes from inflammatory microenvironment-educated MSCs (EX1.25) demonstrated significantly enhanced activity (139.07 ± 5.65%) in promoting dermal fibroblast proliferation compared to control exosomes (118.14 ± 8.09%) [13]. In vivo validation typically involves diabetic or burn wound models in mice, with wound closure rates measured quantitatively. One study reported that on day 6 post-treatment, the percentage of remaining wound area was 40.16 ± 5.44% in the EX1.25 group compared to 54.31 ± 13.14% in the control exosome group [13]. miRNA profiling typically employs sequencing techniques, with bioinformatics analysis (e.g., target prediction using databases like TargetScan) to identify potential miRNA-mRNA interactions [5] [13].

Proteins: Structural and Functional Effectors

Composition and Functional Classes

Exosomal proteins encompass diverse functional classes, including transmembrane proteins, signaling molecules, growth factors, and enzymes. Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81) represent characteristic exosomal membrane proteins that facilitate cellular uptake and may participate in cargo sorting [11]. Exosomes also carry growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which directly stimulate angiogenesis and fibroblast activation [12]. Heat shock proteins (HSPs) within exosomes contribute to cellular stress responses and protein folding, while matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) enable ECM remodeling by degrading matrix components [12]. The specific protein profile varies depending on the cell source and physiological conditions, with MSC-derived exosomes containing a repertoire of proteins that coordinate multiple aspects of tissue repair.

Mechanism of Action in Wound Healing

Exosomal proteins function through several complementary mechanisms. They directly activate signaling pathways in recipient cells through receptor-ligand interactions, with exosomal TGF-β and VEGF receptors capable of initiating downstream signaling cascades [12]. They also process ECM components and modify the wound microenvironment to facilitate cell migration—MMPs from exosomes degrade damaged matrix while facilitating deposition of new collagen [12]. Additionally, exosomal heat shock proteins like HSP60 contribute to quality control and cellular protection under stress conditions prevalent in chronic wounds [11]. The combined action of these proteins accelerates wound resolution by providing both structural support and regulatory signals to cells within the wound bed.

Experimental Characterization Methods

Proteomic characterization of exosomes typically involves mass spectrometry-based analysis, which identifies hundreds to thousands of proteins in a single preparation [12]. Western blotting remains the gold standard for validation of specific protein components, with antibodies against tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81) serving as positive markers and proteins from nucleus, mitochondria, Golgi apparatus, and endoplasmic reticulum considered "non-exosomal" contaminants [11] [13]. Functional assays are protein-specific: angiogenesis is assessed through tube formation assays using human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), inflammatory modulation is measured via nitric oxide (NO) synthesis and cytokine (IL-1β, TNF-α) production in macrophages, and fibrotic potential is evaluated through α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expression in TGF-β1-stimulated fibroblasts [13].

Lipids: Structural Frameworks and Signaling Mediators

Lipid Composition and Biophysical Properties

The lipid bilayer of exosomes is enriched in specific lipid classes that distinguish them from parental cell membranes. Exosomal membranes particularly feature high concentrations of cholesterol, sphingomyelin, and phosphatidylserine compared to plasma membranes [9]. This unique composition contributes to membrane rigidity, stability, and protection of internal cargo from degradation. The external presentation of phosphatidylserine facilitates recognition and uptake by recipient cells, particularly immune cells like macrophages [11]. Additionally, lipid rafts—microdomains enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids—organize signaling molecules and may participate in cargo sorting and exosome biogenesis through their role in membrane curvature [9].

Signaling Functions in Wound Repair

Beyond their structural role, exosomal lipids function as bioactive signaling molecules that influence wound healing processes. Ceramide, for instance, plays a crucial role in exosome biogenesis through the ESCRT-independent pathway and may influence apoptosis and immune responses in recipient cells [11]. Phosphatidylserine externalization contributes to the anti-inflammatory properties of some exosome populations by promoting phagocytic clearance and modulating macrophage polarization [11]. The lipid composition also determines exosome stability and cellular uptake efficiency, with specific lipid profiles potentially enhancing tissue penetration and target cell specificity—critical properties for therapeutic applications in wound healing [9].

Integrated Molecular Networks and Signaling Pathways

The therapeutic efficacy of MSC-derived exosomes emerges from the coordinated action of their molecular components working through integrated signaling networks. Experimental evidence indicates that exosomes regulate fundamental processes including inflammation, angiogenesis, and fibrosis through multi-target mechanisms [5] [13]. The diagram below illustrates the central signaling pathway through which exosomal cargo promotes wound healing.

The diagram above illustrates how exosomal molecular components collectively regulate critical wound healing processes. miRNAs such as miR-146a and miR-223 promote the transition of macrophages from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes, resolving chronic inflammation [6]. Simultaneously, proteins including VEGF and FGF stimulate endothelial cell sprouting and new blood vessel formation, while lipids like phosphatidylserine further support immune modulation [12] [6]. This coordinated regulation across multiple cell types and healing phases underscores the sophisticated communication network mediated by exosomal cargo.

Key signaling pathways modulated by exosomal cargo include the TGF-β/Smad pathway, which regulates fibroblast activation and scar formation [5]. NF-κB signaling represents another critical pathway, particularly in inflammation control, with exosomal miR-146a directly targeting this pathway to reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine production [6]. Additionally, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α) signaling is stimulated by hypoxic-conditioned exosomes, enhancing angiogenic responses in the wound bed [14]. The convergence of these pathways creates a synergistic effect that promotes efficient wound resolution with reduced scarring.

Therapeutic Applications and Engineering Strategies

Native Exosome Therapeutics

Native MSC-derived exosomes have demonstrated significant therapeutic potential across various wound models. In diabetic wound models, MSC exosomes have been shown to improve healing rates by 30-50%, reducing inflammation and promoting functional tissue regeneration [14] [6]. For burn wounds, exosome treatment not only accelerates closure but also ameliorates scarring through coordinated regulation of collagen synthesis and TGF-β signaling pathways [13]. The therapeutic effect stems from the ability of native exosomes to simultaneously modulate multiple aspects of the healing process, addressing the complexity of chronic wounds that often fail conventional treatments.

Engineered Exosome Platforms

To enhance their natural therapeutic properties, researchers are developing sophisticated engineering approaches for exosomes. These include modifying exosome surfaces to improve target specificity through the incorporation of homing peptides or antibodies [9]. Cargo loading techniques are being refined to enhance the packaging of therapeutic miRNAs or drugs, with one study successfully encapsulating 28 key miRNAs into synthetic exosome-like vesicles that demonstrated efficacy comparable to natural exosomes [13]. Hybrid systems combine exosomes with biomaterials such as hydrogels or microneedle patches to improve retention at the wound site and provide controlled release [15] [16] [9]. These engineering strategies address limitations of natural exosomes, including rapid clearance and batch-to-batch variability, while enhancing their therapeutic potential.

Table 3: Experimental Models for Validating Exosomal Therapeutics

| Model System | Application | Key Readouts | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Models | |||

| HUVEC tube formation | Angiogenesis potential | Tube length, branching points | [5] |

| Fibroblast migration assay | Cell motility | Closure rate, migration distance | [13] |

| Macrophage polarization | Immunomodulation | M1/M2 marker expression, cytokine secretion | [15] [13] |

| In Vivo Models | |||

| Diabetic mouse wound model | Chronic wound healing | Wound closure rate, angiogenesis, inflammation | [5] [6] |

| Burn wound model | Burn healing and scarring | Healing time, scar thickness, collagen organization | [13] |

| Full-thickness excision | Acute wound healing | Re-epithelialization, granulation tissue formation | [9] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Exosome Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Total Exosome Isolation Kit | Exosome purification from biofluids | Polymer-based precipitation for high yield |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, CD9, CD81 | Exosome identification | Detection of tetraspanin markers via WB/flow cytometry |

| miRNA Analysis Tools | miRNA sequencing kits; miRNA mimics/inhibitors | Functional miRNA studies | Profiling and functional validation of exosomal miRNAs |

| Cell Culture Reagents | MSC NutriStem XF Medium; human platelet lysate | MSC expansion and exosome production | Serum-free culture for reproducible exosome production |

| Animal Models | Diabetic (db/db) mice; burn wound models | In vivo therapeutic validation | Preclinical assessment of exosome efficacy |

| Biomaterial Scaffolds | Hyaluronic acid hydrogels; chitosan composites | Exosome delivery systems | Enhanced exosome retention and controlled release |

The molecular players within exosomes—miRNAs, proteins, and lipids—orchestrate a sophisticated intercellular communication network that coordinates the complex process of wound healing. miRNAs serve as master regulators of gene expression, proteins function as direct effectors of cellular responses, and lipids provide both structural integrity and signaling capabilities. Together, these components enable MSC-derived exosomes to simultaneously modulate inflammation, promote angiogenesis, stimulate cellular proliferation, and guide tissue remodeling. While challenges remain in standardization, scalable production, and precise delivery, the integrated action of these molecular players positions exosomal therapies as transformative tools for regenerative medicine. Future research focusing on engineering optimized exosomes and understanding their complex molecular networks will unlock further therapeutic potential for challenging wound healing scenarios.

The modulation of inflammation is a cornerstone of effective tissue repair, and the pivotal role of macrophages in this process is increasingly recognized. Macrophages, heterogeneous immune cells of the innate immune system, are not terminal effector cells but possess remarkable functional plasticity [17]. They can adopt a spectrum of activation states in response to microenvironmental cues, with the classically activated pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype and the alternatively activated anti-inflammatory, pro-reparative M2 phenotype representing polar opposites [18]. A timely transition from the M1-dominated inflammatory phase to the M2-dominated reparative phase is critical for successful wound healing [19]. Recent advances in regenerative medicine have highlighted mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exos) as powerful mediators capable of orchestrating this critical polarization shift. This review, framed within the context of a systematic analysis of MSC exosomes in wound healing research, objectively compares the mechanisms and efficacy of different therapeutic approaches in modulating the M1 to M2 transition, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a data-driven guide to this dynamic field.

Macrophage Biology and Polarization Dynamics

Origins and Subtypes of Macrophages

Macrophages populate tissues through two primary developmental pathways, which contribute to their functional diversity. Embryonically-derived macrophages originate from yolk sac progenitors and fetal liver, establishing long-lived, self-renewing populations in tissues such as the brain (microglia), liver (Kupffer cells), and skin (Langerhans cells). These cells are characterized by high expression of CX3CR1 and low expression of CCR2, functioning primarily in immune surveillance and tissue homeostasis [17]. In contrast, bone marrow (BM)-derived macrophages arise from adult hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow. These BM-derived Ly6Chigh monocytes circulate in the blood and are recruited to sites of injury or inflammation, where they differentiate into macrophages. This population is highly adaptable and dynamically responds to microenvironmental demands, playing a crucial role in inflammatory and reparative processes [17].

The Polarization Spectrum: M1 vs. M2 Macrophages

Macrophage polarization exists along a functional continuum, with the well-characterized M1 and M2 states representing two ends of this spectrum.

- M1 Macrophages (Pro-inflammatory): Polarization is classically induced by interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and/or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [18]. These macrophages are potent effector cells that mediate resistance against pathogens and contribute to tissue destruction. Their activation is associated with a specific molecular signature, including high expression of CD86 and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β [19] [17]. Metabolically, M1 polarization is reprogrammed toward glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway [18].

- M2 Macrophages (Anti-inflammatory/Pro-reparative): Polarization is alternatively induced by cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13 [18]. M2 macrophages are key players in the resolution of inflammation, tissue repair, angiogenesis, and fibrosis. They are characterized by high expression of surface markers like CD206 and CD163, and the production of anti-inflammatory factors including IL-10 and TGF-β [19] [17]. Metabolically, M2 polarization favors oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid oxidation [18].

The following diagram illustrates the core macrophage polarization process and its functional outcomes.

Quantitative Comparison of Polarization Markers and Signaling

A systematic understanding of macrophage polarization requires a clear comparison of the defining markers and the signaling pathways that control their activation. The following tables summarize key experimental data and molecular features relevant for researchers designing in vitro polarization experiments or analyzing tissue samples.

Table 1: Characteristic Markers of M1 and M2 Macrophage Polarization

| Category | M1 Macrophage Markers | M2 Macrophage Markers |

|---|---|---|

| Inducing Signals | IFN-γ, LPS [18] | IL-4, IL-13 [18] |

| Cell Surface Markers | CD86 [17] | CD206, CD163 [17] |

| Gene/Protein Markers | CXCL9, CXCL10, NOS2 (iNOS) [19] [18] | MRC1, TGM2, FIZZ1, ARG1 [19] [18] |

| Secreted Cytokines | TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, GM-CSF [19] [18] | IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, TGF-β [19] [17] |

| Metabolic Pathways | Glycolysis, Pentose Phosphate Pathway [18] | Oxidative Phosphorylation, Fatty Acid Oxidation [18] |

Table 2: Key Signaling Pathways in Macrophage Polarization

| Signaling Pathway | Role in M1 Polarization | Role in M2 Polarization | Key Molecular Effectors |

|---|---|---|---|

| JAK-STAT | STAT1 activation by IFN-γ [17] | STAT6 activation by IL-4/IL-13 [17] | JAKs, STAT1, STAT6 |

| NF-κB | Promotes pro-inflammatory gene transcription [17] | Generally suppressed | p65, IκB |

| PI3K-AKT | Contributes to metabolic reprogramming [18] | Supports M2-associated functions [20] | PI3K, AKT, mTOR |

| MEK-ERK | Not critically involved | Critical for M2 polarization; induces PPARγ/retinoic acid signaling [18] [21] | MEK, ERK, PPARγ |

| PPARγ | Inhibited | Master regulator; promotes M2 gene program [18] | PPARγ, RXR |

The dynamic nature of polarization is evident in disease contexts. A study of periapical lesions in mice demonstrated that M1-related markers (Cxcl10, Cxcl9, Nos2) and cytokines (GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α) predominated in initial periods (2-7 days). A shift toward an M2-related profile (Arg1, Fizz1, Ym1, Mrc1 and IL-4, IL-13, IL-10) was observed on day 21, indicating a repair attempt. However, by day 42, the process exacerbated, marked by a return to an M1 profile [19]. This temporal switching underscores the plasticity of macrophages and the potential for therapeutic intervention.

Molecular Mechanisms of Polarization: A Systems View

Global quantitative time-course analyses, including proteomics and phosphoproteomics, have provided unprecedented insight into the molecular machinery driving polarization. These studies reveal that M1 and M2 polarization are associated with extensive and distinct metabolic reprogramming and kinase activation patterns [18] [21].

Kinase-enrichment analysis of phosphoproteomic data has identified specific kinases that are differentially activated during M1- versus M2-type polarization. For instance, a spike in MEK signaling is a hallmark of the induction phase of M2, but not M1, polarization [18]. This finding has direct therapeutic implications, as MEK inhibitors have been shown to selectively block M2 polarization without affecting M1 polarization [18] [21]. Similarly, various histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors also demonstrate a selective inhibitory effect on M2 polarization [18].

The following diagram integrates these molecular events into a coherent signaling network for M2 polarization, a key pathway amenable to therapeutic modulation.

MSC Exosomes as Modulators of Macrophage Polarization

Therapeutic Potential in Wound Healing

Within the context of wound healing, Mesenchymal Stem Cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exos) have emerged as a promising cell-free therapeutic tool. A systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies demonstrates the clear potential of MSC-EVs to be developed as a therapy for wound healing and skin regeneration in both diabetic and non-diabetic animal models [22]. Compared to whole MSCs, MSC-exos offer significant advantages, including lower immunogenicity, absence of infusion toxicity, ease of storage and access, and lack of tumorigenic potential, making them an ideal candidate for biological therapy [23] [24] [20].

The efficacy of MSC-exos is partly attributed to their ability to modulate the immune response, particularly by influencing macrophage polarization. These exosomes can "reduce oxidative stress," "promote angiogenesis," and "modulate the inflammatory response" in the wound microenvironment [23]. A key mechanism is their capacity to reduce pro-inflammatory M1 polarization while promoting anti-inflammatory M2 polarization, thereby facilitating the critical transition from the inflammatory to the proliferative phase of healing [20].

Not all MSC-exos are equivalent. Subgroup analyses from systematic reviews reveal that the therapeutic outcomes can vary depending on the cellular origin of the exosomes.

Table 3: Comparison of MSC Exosome Sources and Efficacy in Wound Healing

| MSC Source | Therapeutic Effects in Wound Healing | Key Mechanisms Related to Macrophages/Repair |

|---|---|---|

| Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs) | Best effect on wound closure rate and collagen deposition [22]. | Regulate oxidative stress, immune cell infiltration, and inflammatory factor secretion [23]. Promote fibroblast and keratinocyte activity via AKT/HIF-1α and ERK/MAPK pathways [23]. |

| Bone Marrow-Derived MSCs (BMSCs) | Better effect on revascularization [22]. | Play active roles in all stages of wound healing; effects mediated through paracrine action of exosomes [20]. |

| Human Umbilical Cord MSCs (hUC-MSCs) | Effective in reducing clinical severity and epidermal hyperplasia in psoriasis models [24]. | Immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties; key mediators of therapeutic benefits of MSCs [24]. |

| Apoptotic Small Extracellular Vesicles (ApoSEVs) | Better efficacy in wound closure outcome and collagen deposition compared to sEVs and ApoBDs [22]. | A newly appraised therapeutic potential; mechanisms under investigation [22]. |

The route of administration also influences efficacy. Subcutaneous injection of MSC-EVs demonstrated a greater improvement in wound closure, collagen deposition, and revascularization compared to topical dressing/covering [22]. Furthermore, in a meta-analysis on psoriasis, meta-regression revealed that studies using hUCMSC exosomes showed a greater improvement in clinical scores compared to other MSC sources [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Experimental Protocols

This section provides a curated list of essential reagents and methodologies for researchers investigating macrophage polarization or developing exosome-based therapies.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Macrophage Polarization Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Polarizing Cytokines | To induce specific macrophage polarization states in vitro. | M1: IFN-γ (20–50 ng/mL), LPS (10–100 ng/mL) [18]. M2: IL-4 (20–50 ng/mL), IL-13 (20–50 ng/mL) [18]. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | To selectively block signaling pathways and study their role in polarization. | MEK inhibitors (e.g., Trametinib, U0126) for selective M2 blockade [18] [21]. HDAC inhibitors (e.g., Trichostatin A) for selective M2 blockade [18]. |

| Surface Marker Antibodies | For identification and sorting of polarized macrophages via flow cytometry. | M1 markers: Anti-CD86 [17]. M2 markers: Anti-CD206, Anti-CD163 [17]. |

| Cytokine Quantification Kits | To measure secreted factors in supernatant or tissue lysates. | Luminex Multiplex Assays for profiling M1 (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) and M2 (IL-4, IL-10, IL-13) cytokines [19]. ELISA kits for individual cytokines. |

| Exosome Isolation Kits | For purification of exosomes from MSC-conditioned media. | Ultracentrifugation (most common), Tangential Flow Filtration, or commercial kit-based methods (e.g., from System Biosciences) [25]. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) | For determining the size distribution and concentration of isolated exosomes. | Instruments such as the ZetaView PMX 110 (Particle Metrix) [24]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: In Vitro Macrophage Polarization and Inhibition

The following protocol is adapted from methodologies used in key studies [18] [21] and can be used to test the effects of MSC-exos or small molecule inhibitors on polarization.

Macrophage Differentiation:

- Use the human monocytic cell line THP-1. Culture cells in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS.

- Differentiate THP-1 monocytes into macrophages (M0) by treating with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) at a concentration of 100 nM for 24 hours.

Polarization Induction:

- After PMA differentiation, wash the cells and replace with fresh medium.

- To induce M1 polarization, treat M0 macrophages with IFN-γ (50 ng/mL) and LPS (50 ng/mL).

- To induce M2 polarization, treat M0 macrophages with IL-4 (50 ng/mL).

- Maintain the polarization treatment for 24 hours to 4 days (for full polarization).

Therapeutic Intervention:

- For testing MSC-exos: Co-treat with isolated MSC-exos (e.g., (1 \times 10^8) to (1 \times 10^9) particles/mL) during the polarization induction period.

- For testing inhibitors: Pre-treat or co-treat with the inhibitor (e.g., MEK inhibitor at 1–10 µM) during the polarization induction period.

Outcome Assessment:

- Protein Analysis: Perform immunoblotting to analyze polarization markers (e.g., TGM2 and MRC1 for M2; IDO1 for M1) [18] [24].

- Gene Expression: Use qRT-PCR to measure mRNA levels of M1 (CXCL9, CXCL10, NOS2) and M2 (ARG1, FIZZ1, MRC1) markers [19].

- Functional Assays: Collect culture supernatant and use Luminex or ELISA to quantify secreted cytokines characteristic of each phenotype [19].

The strategic modulation of inflammation through the induction of a pro-reparative M2 macrophage phenotype represents a powerful therapeutic approach in wound healing and regenerative medicine. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of preclinical data robustly support the potential of MSC-derived exosomes as a cell-free therapy to drive this transition. The efficacy of this approach is influenced by several factors, including the source of MSCs, with ADSC-exos showing particular promise for wound closure and collagen deposition, and the route of administration. The molecular underpinnings of this process involve distinct metabolic and signaling pathways, with MEK/ERK/PPARγ-driven retinoic acid signaling being a critical and druggable axis for M2 polarization. As the field advances, the standardization of exosome isolation, characterization, and application, guided by systematic evidence, will be crucial for translating these promising findings from the bench to the clinic, offering new hope for the treatment of chronic wounds and inflammatory diseases.

Chronic wounds, characterized by a failure to proceed through an orderly and timely healing process, represent a significant global health challenge. A pivotal pathophysiological feature of these wounds is a state of persistent hypoxia, which disrupts the essential process of angiogenesis—the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing vasculature [26] [27]. Effective angiogenesis is crucial for supplying oxygen and nutrients to the healing tissue, and its impairment is a hallmark of conditions like diabetic foot ulcers [28] [29]. Within the context of a systematic review on mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) exosomes for wound healing, this article objectively compares emerging pro-angiogenic strategies. We focus on evaluating the performance of MSC-derived exosomes, gene-activated scaffolds, and other therapeutic approaches, supported by direct experimental data and detailed methodologies to aid researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Pro-Angiogenic Strategies

The following table summarizes the key characteristics and experimental evidence for the primary therapeutic strategies aimed at activating angiogenesis in hypoxic wounds.

Table 1: Comparison of Pro-Angiogenic Strategies for Hypoxic Wound Healing

| Therapeutic Strategy | Key Components / Exosome Source | Primary Angiogenic Mechanisms | Reported Efficacy in Experimental Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSC-Derived Exosomes | ADSC-EVs, hUCMSC-Exos [26] [5] [22] | Promote endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation; modulate macrophages to resolve inflammation; carry pro-angiogenic miRNAs and proteins [26] [28] [5]. | hUCMSC-Exos significantly accelerated wound closure, reduced inflammation, and stimulated angiogenesis in vivo [5]. |

| Gene-Activated Scaffolds | Scaffold + pVEGF/GET nanoparticles (G-VEGF) [30] | Localized, sustained delivery of plasmid DNA for endogenous VEGF production; enhances endothelial cell migration and organization into vascular structures [30]. | G-VEGF scaffolds demonstrated enhanced angiogenic potential and consistently improved neurite outgrowth in vitro and ex vivo [30]. |

| Ozone Therapy | Medical-grade Ozone (O₃) [31] | Induces moderate oxidative stress, stabilizing HIF-1α and enhancing production of VEGF, NO, and PDGF to stimulate capillary formation [31]. | Strong correlation (r=0.84) between ozone exposure and increased VEGF expression in analyzed studies [31]. |

| Natural Products | Various plant-derived compounds [32] | Target endothelial cell function and cross-talk with immune cells and fibroblasts; specific mechanisms driven by unique chemical architectures [32]. | Emerging potential, with activity on angiogenic signals to restore a microenvironment favoring vascular network re-establishment [32]. |

A recent meta-analysis of preclinical studies provides robust, quantitative data on the efficacy of MSC-derived extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs). The analysis, encompassing 83 studies, confirmed that MSC-EVs significantly enhance wound closure and tissue regeneration [22]. Subgroup analyses revealed critical insights for therapeutic development:

- EV Type: Apoptotic small extracellular vesicles (ApoSEVs) showed superior efficacy in wound closure and collagen deposition, while small EVs (sEVs/exosomes) were more effective in revascularization [22].

- Administration Route: Subcutaneous injection provided greater improvement in wound closure, collagen deposition, and revascularization compared to topical dressing/covering [22].

- MSC Source: Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) demonstrated the best effect on wound closure rate, whereas bone marrow MSCs (BMMSCs) were more effective in revascularization [22].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Efficacy Evaluation of hUCMSC-Derived Exosomes

This protocol is adapted from the study by Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology [5].

- Objective: To investigate the therapeutic effects of human umbilical cord MSC-derived exosomes (hUCMSC-Exos) on wound healing and elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

- Methods:

- Exosome Isolation and Characterization: hUCMSC-Exos were isolated from cell culture supernatant via ultracentrifugation. They were characterized using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) for size/concentration, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for morphology, and Western Blot (WB) for positive (CD9, CD63) and negative (Calnexin) markers [5].

- In Vitro Angiogenesis Assay:

- Cell Culture: Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human skin fibroblasts (HSFs) were used.

- Proliferation Assay: Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) was used to assess HSF and HUVEC proliferation after hUCMSC-Exos treatment.

- Migration Assay: A scratch/wound healing assay was performed on HSFs to evaluate migration capability.

- Tube Formation Assay: HUVECs were seeded on Matrigel and observed for their ability to form capillary-like tubular structures. Tube length and number of branch points were quantified [5].

- In Vivo Wound Healing Model:

- Animal Model: A full-thickness excisional wound model was established on mice.

- Treatment: hUCMSC-Exos or a control (e.g., PBS) were administered via local injection.

- Assessment: Wound closure rate was measured over time. Harvested skin tissues were subjected to:

- Histological & Immunohistochemical Analysis: Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for general morphology and epidermal thickness; Masson's trichrome staining for collagen deposition; immunohistochemistry for CD31 (to mark blood vessels) and other inflammatory or proliferation markers [5].

- Bioinformatics Analysis: miRNA sequencing and target prediction were performed to identify potential key molecules (e.g., ULK2, COL19A1, IL6ST) involved in the repair process [5].

Protocol 2: Development and Testing of a VEGF-Activated Scaffold

This protocol is adapted from the study published in Biomaterials Science [30].

- Objective: To develop a scaffold capable of localized gene delivery to enhance both angiogenesis and nerve repair in chronic wounds.

- Methods:

- Nanoparticle Formulation: The GET peptide and plasmid DNA encoding VEGF (pVEGF) were combined at a fixed charge ratio (6:1) in OptiMEM to form self-assembling G-VEGF nanoparticles [30].

- Nanoparticle Characterization:

- Size and Zeta Potential: Analyzed using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA).

- Stability: Assessed via gel electrophoresis after incubation with DNase I and fetal bovine serum (FBS) to confirm protection against degradation [30].

- In Vitro Transfection and Bioactivity:

- Cell Transfection: Dermal fibroblasts were transfected with G-VEGF nanoparticles. VEGF protein expression in the supernatant was quantified using an ELISA kit.

- Cell Viability: Cytotoxicity was assessed using a metabolic activity assay (e.g., AlamarBlue).

- Endothelial Cell Migration: A scratch assay was performed with HUVECs cultured with conditioned media from transfected fibroblasts.

- Tube Formation Assay: HUVECs were seeded on Matrigel and cultured with conditioned media to observe vascular structure formation [30].

- Neurogenic Potential Assessment:

- In Vitro Neurite Outgrowth: Neural cells were cultured on the VEGF-activated scaffolds, and neurite length was measured.

- Ex Vivo Model: Dorsal root ganglia (DRG) were explanted and cultured on the scaffolds to evaluate axon extension [30].

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Key Angiogenic Signaling Pathways Activated by Exosomes

The following diagram illustrates the core molecular pathways through which MSC-derived exosomes promote angiogenesis in hypoxic wounds, integrating mediators from multiple studies [28] [5] [29].

Experimental Workflow for Evaluating Pro-Angiogenic Therapies

This flowchart outlines a standardized experimental pipeline for developing and testing pro-angiogenic therapies, from isolation to in vivo validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting research in angiogenesis and wound healing, as derived from the experimental protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Angiogenesis Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Cellular source for deriving exosomes and conditioned media; used to study paracrine effects. | Human Umbilical Cord MSCs (hUCMSCs), Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs) [26] [5] [22]. |

| Extracellular Vesicle Isolation Kits | Isolate and purify exosomes and other EVs from cell culture media or biological fluids. | Ultracentrifugation protocols; Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) systems [5] [22]. |

| Characterization Instruments | Physically characterize isolated vesicles (size, concentration, morphology). | Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (NTA; e.g., ZetaView, NanoSight); Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM); Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) instrument [24] [30] [5]. |

| Endothelial Cell Culture Systems | In vitro models for studying angiogenesis mechanisms (proliferation, migration, tube formation). | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs); capillary formation assays using Matrigel or other ECM substitutes [30] [5]. |

| Animal Wound Models | In vivo systems to test the therapeutic efficacy of pro-angiogenic treatments. | Diabetic (e.g., db/db mice, STZ-induced) and non-diabetic murine full-thickness excisional wound models [22]. |

| Gene Delivery Vectors | Facilitate the transfer of therapeutic genes (e.g., pVEGF) into target cells. | Non-viral vectors (e.g., GET peptide system); commercial transfection reagents (e.g., lipofectamine 3000) [30]. |

| Biomaterial Scaffolds | Provide a 3D structure for cell attachment, proliferation, and localized delivery of therapeutics. | Collagen-based scaffolds; functionalized scaffolds for gene activation (Gene-Activated Scaffolds) [30]. |

| Angiogenesis Assay Kits | Quantitatively measure key angiogenic parameters in vitro and ex vivo. | Tube formation assay kits; ELISA kits for VEGF and other growth factors; immunohistochemistry kits for CD31/PECAM-1 staining [30] [5]. |

The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine, particularly in the context of wound healing. As a cell-free alternative, these nanoscale extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm in diameter) mediate the paracrine effects of their parent cells by transferring bioactive molecules—including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—to recipient cells [33] [34]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical wound healing studies confirms that exosome administration significantly improves therapeutic outcomes, with the highest efficacy observed at seven days post-application (odds ratio 1.82, 95% CI [0.69, 2.95]) [25]. This review synthesizes current evidence demonstrating how MSC-derived exosomes systematically enhance keratinocyte and fibroblast function, the key cellular players in cutaneous regeneration, through defined signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms.

Comparative Efficacy of MSC Exosomes on Target Cells

Quantitative Effects on Cellular Functions

MSC-derived exosomes exert pleiotropic effects on skin cells, significantly enhancing processes critical for wound repair. The table below summarizes their differential impacts on keratinocytes and fibroblasts based on experimental data.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of MSC-Derived Exosomes on Keratinocytes and Fibroblasts

| Cell Type | Proliferation | Migration | Key Functional Outcomes | Signaling Pathways Activated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keratinocytes | Dose-dependent enhancement [35] | Accelerated re-epithelialization [36] | Enhanced epidermal barrier restoration [36] | PI3K/Akt, ERK, STAT3 [35] [36] |

| Fibroblasts | Dose-dependent enhancement [35] | Significant migration promotion [35] [5] | Increased collagen deposition [25] | Akt, ERK, STAT3 [35] |

| Endothelial Cells | Increased proliferation [5] | Enhanced tube formation [35] [5] | Improved angiogenesis [25] [5] | PI3K/Akt [36] |

Comparative Performance Against Alternative Approaches

When evaluated against other therapeutic strategies, MSC exosomes demonstrate distinct advantages in modulating cellular behavior.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of MSC Exosomes Versus Alternatives

| Therapeutic Approach | Effect on Keratinocyte Proliferation | Effect on Fibroblast Migration | Angiogenic Potential | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSC-Derived Exosomes | Significant, dose-dependent enhancement [35] [36] | Significant, dose-dependent enhancement [35] | Promotes tube formation [35] [5] | Manufacturing standardization challenges [37] |

| Whole MSC Therapy | Enhancement observed [35] | Enhancement observed [35] | Promotes angiogenesis [35] | Risk of microvasculature occlusion, immunogenicity [34] |

| Conventional Treatments | Variable effects | Variable effects | Limited | High non-response rates in chronic wounds [35] |

| Platelet-Rich Plasma | Moderate enhancement | Moderate enhancement | Moderate | Variable composition, donor-dependent efficacy |

Experimental Data and Methodologies

Key Experimental Protocols

Exosome Isolation and Characterization

The majority of studies (64%) employ ultracentrifugation for exosome isolation, while 18% use commercial kits, and 7% combine ultracentrifugation with filtration [25]. The standard protocol involves:

- Differential Ultracentrifugation: Sequential centrifugation steps (500 ×g to remove cells, 10,000 ×g to remove debris, and 100,000-120,000 ×g for exosome pelleting) [33]

- Characterization: Multiparameter analysis using nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and western blot for surface markers (CD63, CD9, CD81, TSG101) [25] [5]

- Quantification: Protein content determination via BCA assay [35]

In Vitro Functional Assays

- Fibroblast Migration Assay: Coculture systems with labeled MSCs and fibroblasts demonstrate enhanced migration without direct cell contact, confirming paracrine mediation [35]

- Keratinocyte Proliferation Assay: MSC exosomes internalized by keratinocytes activate proliferative pathways (Akt, ERK) [35] [36]

- Tube Formation Assay: Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with MSC exosomes show increased tube formation, indicating enhanced angiogenic potential [35] [5]

In Vivo Wound Healing Models

- Animal Models: Rodent excisional wound models (32 mice studies, 19 rat studies) treated with topical exosome applications [25]

- Efficacy Assessment: Wound closure rate measurement, histological analysis for re-epithelialization and collagen deposition, immunohistochemical staining for cellular proliferation markers [5]

- Dosing: Optimal effects observed with multiple applications; meta-analysis supports standardized concentration guidelines [25]

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Key Signaling Pathways in Keratinocyte Proliferation

MSC exosomes activate multiple interconnected signaling pathways to enhance keratinocyte function:

Diagram 1: Exosome-mediated signaling in keratinocytes (Title: Keratinocyte Signaling Pathways)

Fibroblast Activation and Matrix Remodeling

For dermal fibroblasts, MSC exosomes utilize distinct mechanisms to promote migration and extracellular matrix production:

Diagram 2: Fibroblast signaling and functional outcomes (Title: Fibroblast Signaling Pathways)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for MSC Exosome Studies

| Reagent/Technique | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ultracentrifugation | Exosome isolation via sequential centrifugation | Standardized purification from conditioned media [35] [33] |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis | Size distribution and concentration measurement | Characterizing exosome preparations (30-150 nm) [25] [5] |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy | Morphological visualization | Confirming cup-shaped exosome morphology [35] [25] |

| Western Blot | Protein marker confirmation | Detecting CD63, CD9, CD81, TSG101 [25] |

| PKH26 Labeling | Fluorescent exosome tracking | Cellular uptake and localization studies [35] |

| Transwell Assays | Migration quantification | Measuring fibroblast and keratinocyte migration [35] [5] |

| Tube Formation Assay | Angiogenic potential assessment | Evaluating endothelial cell function [35] [5] |

MSC-derived exosomes represent a sophisticated cell-free therapeutic platform that effectively enhances keratinocyte and fibroblast function through defined molecular mechanisms. The experimental evidence demonstrates their consistent, dose-dependent effects on cellular proliferation and migration, mediated through Akt, ERK, and STAT3 signaling pathways, along with specific miRNA-mediated regulation. While manufacturing scalability and standardization remain challenges, the compelling preclinical data and ongoing clinical translation efforts position MSC exosomes as a promising therapeutic modality in regenerative medicine. Their ability to coordinate multiple aspects of the wound healing process without the risks associated with whole-cell therapies underscores their potential to address the significant unmet needs in chronic wound management.

Cutaneous wound healing is a complex biological process aimed at restoring the skin's barrier function following injury. In adult humans, this process typically results in the replacement of damaged functional tissue with a collagen-rich patch known as a scar [38] [39]. Whereas scarring achieves rapid wound closure, it represents a compromise: scar tissue never achieves the flexibility, strength, or functionality of the original skin, with maximum tensile strength reaching only approximately 80% of uninjured skin [38]. This compromise stems primarily from aberrations in extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, particularly in the deposition and organization of collagen fibers [38] [40].

The ECM is not merely a structural scaffold but a dynamic, organized mesh of macromolecules that regulates cell migration, proliferation, differentiation, and growth factor bioavailability [38]. Abnormal ECM reconstruction during wound healing contributes to pathological scarring, manifesting as hypertrophic scars or keloids that cause significant physical dysfunction and psychological stress [38] [41]. Currently, there exists no satisfactory treatment for these conditions, partly due to incomplete understanding of their underlying mechanisms [38].

This review examines the delicate balance between collagen deposition and scar formation within the context of ECM remodeling, with particular emphasis on emerging therapeutic strategies involving mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes. By comparing the compositional and structural differences between normal and pathological scarring, and detailing the experimental approaches used to investigate them, we aim to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive resource for advancing regenerative therapeutics.

ECM Composition and Collagen Dynamics in Skin Repair

The Extracellular Matrix Microenvironment

The skin's extracellular matrix provides both structural integrity and biochemical signaling crucial for homeostasis and repair. The cutaneous ECM comprises a complex assortment of proteins including:

- Structural proteins (collagens, laminins, elastins)

- Proteoglycans and hyaluronan (stabilizing growth factors and hydrating the matrix)

- Glycoproteins such as integrins (regulating cell adhesion and signaling) [38]

This microenvironment interacts dynamically with local cells, particularly fibroblasts, which are the primary ECM producers [38] [42]. The ECM serves as a reservoir for growth factors like TGF-β, FGF, and VEGF, with degradation of ECM proteins during wound healing inducing local release of these factors to modulate the repair process [38].

Collagen Structure and Assembly

Collagens constitute approximately three-quarters of the dry weight of human skin, making them the most prevalent ECM component [40]. Among the 28 known collagen types, type I and type III are the main dermal collagens, constituting roughly 80-85% and 8-11% of the dermal ECM, respectively [40].

All collagens are synthesized as procollagen chains with N- and C-terminal propeptides flanking the collagen helical region [40]. The triple helix formation begins with C-terminal propeptide interactions, leading to alignment of three polypeptide chains held together by interchain hydrogen bonds in a characteristic Gly-X-Y repeat pattern (where X and Y are frequently proline and hydroxyproline) [40]. Following secretion, propeptides are cleaved, and collagen molecules assemble into fibrils through a linear staggered array stabilized by enzymatic cross-linking mediated by lysyl oxidases (LOXs) [38] [40]. This cross-linking provides fibrils with mechanical resilience and contributes to the skin's mechanical strength [40].

Table 1: Key Collagen Types in Normal Skin

| Collagen Type | % Total Skin | Location | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 80-85% | Dermis | Main structural collagen providing tensile strength |

| III | 8-11% | Dermis | Provides flexibility and softness; regulates fibril diameter |

| IV | 2-4% | Basement membrane | Supports epidermal-dermal separation |

| V | <1% | Basement membrane, dermis | Bridges and stabilizes epidermal-dermal interface |

The Wound Healing Cascade and ECM Remodeling

Wound healing progresses through overlapping phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [43] [39]. The final remodeling phase can last up to a year or more, during which the immature scar undergoes significant ECM reorganization [38] [39].

During proliferation, fibroblasts deposit disorganized type III collagen in granulation tissue [42]. In normal remodeling, this is gradually replaced by type I collagen, and the fibrils become more organized [42] [41]. Critical to this process is the balanced activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their inhibitors (TIMPs), which degrade and reorganize the ECM [38] [42]. Any disturbance in this balance can lead to either poor wound healing or excessive scarring [43].

Figure 1: The Relationship Between Wound Healing Phases and ECM Dynamics

Comparative Analysis: Normal Skin vs. Pathological Scars

Structural and Compositional Differences

Pathological scars (hypertrophic scars and keloids) demonstrate significant deviations from normal skin architecture in their collagen composition and organization. Whereas normal skin collagen fibrils form a complex network of interlaced basketweave-like fibrils with diameters averaging 110-130 nm, pathological scars show substantially thinner fibrils (~60-70 nm) despite having thicker collagen fiber bundles [40].

The collagen ratio is also altered in pathological scarring. Although the relative ratio of type III to type I collagen is reduced compared to normal skin, the expected corresponding increase in fibril diameter does not occur, suggesting additional regulatory defects [40]. Keloids in particular show irregular accumulation of both type I and type III collagen, whereas hypertrophic scars display tightly arranged type III collagen with less type I [41].

Table 2: Collagen Characteristics in Normal Skin vs. Pathological Scars

| Parameter | Normal Skin | Hypertrophic Scar | Keloid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average fibril diameter | ~110-130 nm | ~60 nm | ~60-70 nm |

| Collagen fiber orientation | Mainly parallel to skin surface with minor out-of-plane components | Mainly parallel to epithelial surface | Random orientation to epithelial surface |

| Fiber bundle thickness | Reference thickness | Thinner than normal skin | Thicker than normal skin and hypertrophic scars |

| Fiber packing | Majority closely packed in parallel array | Loosely arrayed in wavy pattern | Packed loosely with irregular spacing |

| LOX activity | Normal baseline | Comparable to normal skin | Elevated |

Cellular Mechanisms Driving Pathological Scarring

Fibroblasts and their activated form, myofibroblasts, are key players in pathological scarring [42]. Myofibroblasts are characterized by expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and prominent stress fibers, granting them contractile properties [42]. These cells secrete abundant ECM components and play a major role in wound contraction and matrix maturation [42] [39].

In normal wound healing, myofibroblasts undergo apoptosis during the remodeling phase. However, in pathological scarring, they persist, leading to excessive collagen deposition and contraction [42]. The origin of these myofibroblasts may include local fibroblast activation, circulating fibrocytes, and differentiation from local mesenchymal stem cells [42].

Mechanical force has emerged as a crucial regulator of fibrotic healing. Mechanical tension activates focal adhesion kinase (FAK) pathways, leading to inflammatory signaling and fibrosis [44]. Inhibition of FAK signaling in preclinical models attenuates fibrotic scar formation while accelerating healing [44].

The Inflammation-Scarring Connection

The role of inflammation in scarring is well-established. Compared to adult wounds that heal with scars, fetal wounds that heal scarlessly have a markedly reduced inflammatory response [38]. Similarly, oral mucosa wounds heal with minimal scar formation and have lower levels of macrophage, neutrophil, and T-cell infiltration [38].

Prolonged inflammation disrupts the normal balance of MMPs and TIMPs, favoring either ECM degradation (chronic wounds) or excessive accumulation (hypertrophic scars/keloids) [43]. In chronic wounds, elevated levels of MMPs (particularly collagenase and gelatinase) excessively degrade ECM components, while in hypertrophic scars and keloids, reduced MMP activity or elevated TIMPs leads to collagen accumulation [43] [39].

MSC Exosomes: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential in ECM Remodeling

Biogenesis and Characteristics of MSC Exosomes

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes are nanoscale extracellular vesicles (40-150 nm in diameter) formed through the inward budding of endosomal membranes, resulting in multivesicular bodies that subsequently fuse with the plasma membrane to release their contents into the extracellular space [43] [45]. These vesicles contain proteins, lipids, mRNAs, and miRNAs, and function as key mediators of intercellular communication [43].

As therapeutic agents, MSC exosomes offer several advantages over their parent cells:

- Lower immunogenicity and reduced risk of tumorigenicity [6] [45]

- Enhanced stability and ability to cross biological barriers [6] [45]

- Easier storage and distribution without losing biological activity [45]

- No risk of vascular occlusion or ectopic tissue formation [6]

Molecular Mechanisms in Wound Healing and Scar Reduction

MSC exosomes facilitate wound healing through multiple mechanisms across all phases of repair:

Inflammation Phase: Exosomal miRNAs such as miR-146a and miR-223 inhibit NF-κB signaling and suppress NLRP3 inflammasome activation, promoting the transition from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages [6]. This polarization is critical for resolving inflammation and preventing excessive scarring [38] [6].

Proliferation Phase: Exosomes from MSCs and adipose-derived stem cells enhance fibroblast proliferation and migration by delivering miR-21, miR-29a, and other miRNAs that optimize ECM production [6]. They also promote angiogenesis through transfer of pro-angiogenic factors [6].

Remodeling Phase: MSC exosomes help restore a more balanced collagen ratio by modulating TGF-β signaling and MMP/TIMP expression, leading to better organized ECM architecture with reduced cross-linking and collagen density characteristic of normal skin rather than scars [43] [6].

Figure 2: MSC Exosome Mechanisms in ECM Remodeling and Scar Reduction

Experimental Evidence and Comparative Efficacy

Preclinical studies demonstrate the efficacy of MSC exosomes in promoting regenerative healing. In animal models of impaired wound healing, MSC exosomes significantly accelerate wound closure, improve epithelialization, enhance angiogenesis, and reduce scar formation [43] [6]. The therapeutic effects appear comparable to MSC therapy but with improved safety profiles [6].

The source of MSCs influences exosome composition and efficacy. Exosomes derived from different sources (bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord) show variations in their miRNA profiles and regenerative properties [6] [45]. Additionally, engineering approaches to enhance exosome targeting and potency, such as preconditioning MSCs or modifying exosome content, are under active investigation [45].

Experimental Methodologies for Studying ECM Remodeling

Analytical Techniques for Collagen Characterization

Research on ECM remodeling employs sophisticated techniques to analyze collagen structure, composition, and organization:

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) provides high-resolution imaging of collagen fibril ultrastructure, allowing precise measurement of fibril diameter and assessment of cross-linking patterns [40]. This technique revealed the significantly reduced fibril diameter in keloids (~76 nm) compared to normal skin (~124 nm) [40].

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) enables three-dimensional visualization of collagen fiber organization and packing, demonstrating the parallel orientation in hypertrophic scars versus random orientation in keloids [40].

Histological staining techniques including Masson's Trichrome and Picrosirius Red provide qualitative and quantitative assessment of collagen content and distribution in tissue sections [40].

X-ray diffraction studies help determine the molecular arrangement of collagen fibrils and the positions of different collagen types within hybrid fibrils [40].

In Vitro and In Vivo Models

Fibroblast cultures from normal skin and pathological scars allow investigation of collagen synthesis rates, gene expression profiles, and response to therapeutic interventions [40] [41]. These models have identified differences in TGF-β responsiveness and proliferation capacity between keloid fibroblasts and normal fibroblasts [41].

Animal models of wound healing, including rodent, porcine, and rabbit models, enable assessment of scar formation and ECM remodeling in a complex physiological environment [44]. The PU.1 null mouse model, which lacks neutrophils and macrophages, has been instrumental in studying inflammation-independent healing [38] [41].

Mechanical force models apply controlled tension to healing wounds to investigate mechanotransduction pathways in fibrosis, leading to identification of FAK as a key mediator [44].

Table 3: Experimental Models for Studying Scar Formation and ECM Remodeling

| Model Type | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal vs. keloid fibroblast cultures | Collagen synthesis, gene expression, drug screening | Controlled environment, mechanistic studies | Lacks tissue complexity and systemic factors |

| Rodent wound models | Initial therapeutic screening, scar assessment | Cost-effective, readily available | Healing differs from humans (more contraction) |

| Porcine wound models | Scar formation evaluation, therapeutic testing | Skin structure similar to humans | Expensive, specialized facilities required |

| PU.1 null mouse | Inflammation-scarring relationship | Genetic absence of inflammatory cells | Not representative of normal healing |

| Mechanical stress models | Mechanotransduction pathways | Clinically relevant to human scarring | Challenging to standardize |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for ECM and Scarring Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| TGF-β inhibitors | Investigate role of TGF-β signaling in fibrosis | SB-431542, neutralizing antibodies |

| FAK inhibitors | Study mechanotransduction in scarring | VS-6062 (FAK inhibitor) |

| LOX inhibitors | Assess collagen cross-linking in scarring | β-aminopropionitrile (BAPN) |

| MMP inhibitors | Probe ECM degradation balance | GM6001, TIMP overexpression |

| Collagen analysis kits | Quantify collagen content and types | Sircol assay, type-specific ELISAs |

| α-SMA antibodies | Identify myofibroblasts in tissues | Immunofluorescence, Western blot |

| MSC exosome isolation kits | Prepare therapeutic vesicles | Ultracentrifugation, commercial kits |

| Hydrogel delivery systems | Controlled release of therapeutics | Hyaluronic acid hydrogels with FAK-i |

The balance between collagen deposition and scar formation represents a central challenge in cutaneous wound healing. Current evidence confirms that pathological scarring stems from disruptions in normal ECM remodeling, characterized by aberrant collagen composition, organization, and cross-linking. The emergence of MSC exosomes as acellular therapeutics offers a promising approach to modulate this process, addressing multiple phases of wound healing simultaneously through anti-inflammatory, pro-angiogenic, and optimized regenerative mechanisms.

Future research priorities include standardizing exosome production protocols, enhancing targeted delivery to wound sites, and identifying optimal MSC sources for specific clinical applications. The integration of bioengineering approaches with biological insights—such as combining MSC exosomes with controlled-release scaffolds or mechanical tension-offloading devices—may further advance the field toward the ultimate goal of scarless regenerative healing. As our understanding of ECM biology deepens, particularly regarding fibroblast heterogeneity and mechanotransduction pathways, new therapeutic targets will undoubtedly emerge, offering hope for the millions affected by pathological scarring worldwide.

From Bench to Bedside: Isolation, Characterization and Delivery Strategies for MSC Exosomes