Three-Dimensional Microenvironments: Revolutionizing Cellular Reprogramming for Regenerative Medicine and Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative role of three-dimensional (3D) microenvironments in enhancing the efficiency and functionality of cellular reprogramming.

Three-Dimensional Microenvironments: Revolutionizing Cellular Reprogramming for Regenerative Medicine and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of three-dimensional (3D) microenvironments in enhancing the efficiency and functionality of cellular reprogramming. Moving beyond traditional two-dimensional (2D) cultures, 3D systems more faithfully recapitulate native stem cell niches, leading to improved reprogramming outcomes for generating induced neurons, hepatic organoids, and alveolar epithelial cells. We cover the foundational principles of how 3D geometry and cell-cell interactions boost reprogramming, detail cutting-edge methodological applications, address key troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and provide a comparative analysis of 3D vs. 2D outcomes. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage 3D reprogramming for advanced disease modeling, pharmaceutical applications, and regenerative therapies.

The Core Principles: How a 3D Microenvironment Reshapes Cell Fate

The regenerative capacity, plasticity, and pathological conversion of stem cells are determined as much by their surrounding three-dimensional (3D) niche as by the intrinsic properties of the cells themselves [1]. This represents a significant shift in perspective—from a cell-centric to a niche-centric view—that forms the conceptual foundation for modern regenerative medicine. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell culture systems, while useful for simplified experiments, fail to recapitulate the architectural, mechanical, and biochemical complexity of native stem cell microenvironments [2]. This application note examines the fundamental role of 3D structure in stem cell niches and provides detailed methodologies for recreating these environments to enhance the fidelity of cellular reprogramming research and drug development.

Architectural Components of the Stem Cell Niche

Stem-cell niches are anatomically discrete microenvironments where resident stem cells, their stromal neighbors, and a specialized extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffold cooperate to balance quiescence, self-renewal, and lineage commitment [1]. The following table summarizes the core components across diverse tissue types:

Table 1: Core Components of Stem Cell Niches Across Tissues

| Tissue (Representative Niche) | Core Cellular Constituents | ECM/Mechanical Hallmark | Dominant Signaling Axes | Primary Homeostatic Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow (endosteal and perivascular) | Osteoblasts, sinusoidal endothelial cells, CAR cells, LepR+ MSCs, macrophages | 3D trabecular matrix; oxygen and CXCL12 gradients | Wnt BMP, Notch, Tie2/Ang-1 | Balance quiescence vs. rapid hematopoietic output |

| Intestinal crypt | Lgr5+ stem cells, Paneth cells, pericryptal myofibroblasts | 2-D basement membrane; steep Wnt/BMP gradient | Wnt3, Dll4/Notch, EGF, BMP | Continuous epithelial renewal |

| Skin (hair follicle bulge) | K15+ bulge stem cells, dermal papilla fibroblasts, melanocyte progenitors | Flexible basement membrane; low stiffness | Wnt/Shh, BMP antagonists | Cyclic hair regeneration and wound repair |

| Neural (SVZ/SGZ) | GFAP+ NSCs, endothelial cells, ependymal cells, microglia | Laminin-rich fractal matrix; CSF contact | FGF, EGF, IGF-1, Wnt, BMP | Adult neurogenesis and cognitive plasticity |

| Skeletal muscle (satellite) | Pax7+ satellite cells, FAPs, macrophages, endothelial cells | Sub-laminar niche; rapid viscoelastic relaxation | HGF/c-Met, FGF2, Notch, Wnt | Myofiber repair and hypertrophy control |

| Heart (sub-epicardial CSC niche) | c-Kit+/Sca1+ CSCs, cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, vSMCs | Low-stress ECM; anisotropic stiffness | VEGF, TGF-β, HIF-1α, Wnt | Paracrine support and limited cardiomyocyte turnover |

The ECM provides both a structural lattice and a reservoir of biochemical and mechanical cues. Laminin, collagen, fibronectin, and proteoglycans organize spatial relationships between niche residents, create morphogen gradients, and transmit force [1]. Integrins and cadherins on the stem-cell surface translate ECM stiffness, viscoelasticity, and topography into intracellular signaling cascades that steer proliferation or differentiation [1].

Quantitative Evidence: Enhanced Reprogramming in 3D Microenvironments

Recent research provides compelling quantitative evidence that 3D microenvironments significantly enhance cellular reprogramming efficiency compared to traditional 2D cultures. A seminal study demonstrated that a tissue-engineered 3D hydrogel environment enhanced microRNA-mediated reprogramming of fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes [3]. The following table summarizes the key quantitative findings:

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Reprogramming Efficiency in 2D vs. 3D Cultures

| Parameter | 2D Culture Results | 3D Culture Results | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming efficiency (CFP+ cells) | 7.8% CFP(+) cells for miR combo | 23.1% CFP(+) cells for miR combo | ~3-fold increase in 3D |

| Fold-increase over control | ~5-fold increase | ~20-fold increase | 4x greater relative improvement in 3D |

| Cardiac gene expression (αMHC, cTnI, etc.) | Moderate increase | Significantly enhanced mRNA levels | p < 0.05 for all cardiac markers |

| MMP expression | Baseline levels | Strongly induced MMP-2 and MMP-3 | MMP activity necessary for enhanced reprogramming |

| Pharmacological MMP inhibition | N/A | Abolished enhanced cardiac reprogramming | Confirms MMP-dependent mechanism |

This research demonstrated that culturing fibroblasts within a 3D fibrin-based hydrogel environment significantly improves the efficiency of direct cardiac reprogramming by miR combo as assessed by gene and protein expression of early and later cardiac differentiation markers [3]. The improved cardiac reprogramming is mediated by enhanced expression of Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) in the 3D culture environment, and pharmacological inhibition of MMPs blocks this enhancing effect [3].

Experimental Protocol: 3D Hydrogel-Based Fibroblast to Cardiomyocyte Reprogramming

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for 3D Reprogramming Protocols

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogel Polymers | Fibrin, collagen, Matrigel, PEG-based hydrogels | Provides 3D scaffold mimicking native ECM structure and mechanics |

| Reprogramming Factors | miR combo (miR-1, miR-133, miR-208, miR-499), OSKM factors | Induces transdifferentiation or pluripotency; initiates lineage conversion |

| MMP Modulators | Broad-spectrum inhibitor BB94 (Batimastat), MMP-2/MMP-9 inhibitors | Investigates MMP-dependent mechanisms in 3D reprogramming |

| Cell Sources | Neonatal cardiac fibroblasts, tail-tip fibroblasts, lineage-traced cells (Fsp1-tdTomato) | Provides starting population for reprogramming; enables lineage tracing |

| Characterization Tools | αMHC-CFP reporter mice, Fsp1-tdTomato lineage tracer, cardiac-specific antibodies | Tracks reprogramming efficiency and confirms cardiomyocyte identity |

Detailed Methodology

Step 1: Hydrogel Preparation and 3D Construct Fabrication

- Prepare fibrinogen solution at 10 mg/mL in serum-free DMEM

- Thrombin solution at 2 U/mL in DMEM

- Suspend fibroblasts at 10 × 10^6 cells/mL in fibrinogen solution

- Mix cell-fibrinogen suspension with thrombin solution at 9:1 ratio

- Pipette 100 μL aliquots into custom-made rectangular molds (10 × 5 × 2 mm)

- Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes for complete polymerization

- Transfer tissue bundles to 6-well plates with 3 mL culture medium

Step 2: microRNA Transfection and Induction

- Transfect fibroblasts with miR combo (miR-1, miR-133, miR-208, miR-499) or negative control microRNA using appropriate transfection reagent

- Use final concentration of 50 nM for each microRNA in the combination

- For 3D groups, perform transfection prior to hydrogel encapsulation

- Culture constructs for 14 days with medium changes every 48 hours

Step 3: MMP Inhibition Studies

- Prepare BB94 (Batimastat) stock solution at 10 mM in DMSO

- Add to culture medium at final concentration of 10 μM

- Refresh inhibitor-containing medium every 48 hours

- Include vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) for comparison

Step 4: Assessment of Reprogramming Efficiency

- At day 14, analyze constructs for cardiac markers:

- Quantitative PCR for αMHC, Cardiac troponin-I, α-Sarcomeric actinin, Kcnj2

- Immunostaining for Cardiac troponin-T and α-Sarcomeric actinin

- Flow cytometry for CFP expression in αMHC-CFP reporter system

- Confocal imaging for structural analysis of reprogrammed cells

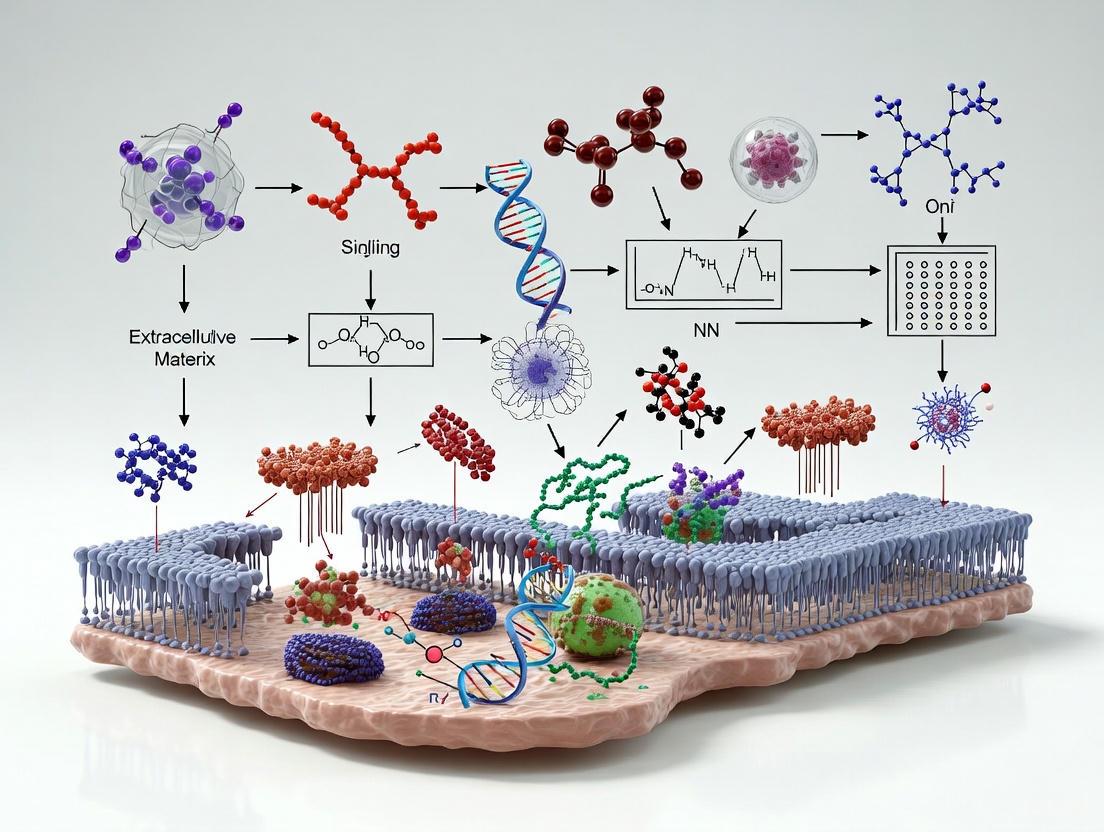

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for 3D cellular reprogramming.

Computational and Imaging Tools for Niche Analysis

Computational Modeling of Stem Cell Niches

Advanced computational methods are revolutionizing our ability to identify and characterize stem cell niches from spatially resolved omics data. NicheCompass is a graph deep-learning method that models cellular communication to learn interpretable cell embeddings that encode signaling events, enabling the identification of niches and their underlying processes [4]. This approach:

- Constructs spatial neighborhood graphs where nodes represent cells/spots and edges indicate spatial proximity

- Uses a graph neural network encoder to generate cell embeddings capturing microenvironments

- Incorporates domain knowledge of intercellular and intracellular interaction pathways

- Identifies signaling-based niches and characterizes their specific activities

- Enables quantitative comparison of niche organization across developmental stages, healthy and diseased tissues, and treatment conditions

Virtual Cell (VCell) modeling software provides a comprehensive platform for mathematical modeling of cell biological systems, including stem cell niches [5]. This web-based resource enables researchers to create computational models that integrate spatial and temporal aspects of niche signaling, including reaction-diffusion processes, mechanical interactions, and biochemical signaling networks.

Advanced 3D Live Cell Imaging

Label-free live cell imaging in 3D represents a breakthrough for monitoring stem cell dynamics within engineered niches. Holotomographic microscopy (e.g., 3D Cell Explorer) enables long-term imaging of fine cellular dynamics with minimal phototoxicity, capturing stem cell behaviors in their native 3D context [6]. Key advantages include:

- Injection of ~100 times less energy (~0.2 nW/µm²) than light sheet microscopes

- Resolution of 195nm enabling visualization of mitochondria, lipid droplets, filopodia, and nuclear dynamics

- Continuous imaging capability with acquisition rates up to 1 image per 1.7 seconds

- Combination with fluorescence imaging for multimodal analysis

- Preservation of native cell function through avoidance of phototoxic damage

Figure 2: Signaling mechanisms in 3D stem cell niches.

Application in Disease Modeling: Biomimetic 3D Environments

The critical importance of 3D microenvironments extends to disease modeling, where engineered niches enable more accurate representation of pathological processes. Recent advances in 3D bioprinting and ECM-like biomaterials have facilitated the development of biomimetic models for conditions such as polycystic kidney disease, demonstrating how tuning the 3D microenvironment enhances disease modeling accuracy [7]. These approaches allow researchers to:

- Recreate disease-specific ECM composition and stiffness

- Model spatial organization of multiple cell types within pathological niches

- Recapitulate gradient-dependent signaling abnormalities

- Test therapeutic interventions in a more physiologically relevant context

Similarly, in cancer research, NicheCompass has been deployed to decode the tumor microenvironment, capturing donor-specific spatial organization and cellular processes [4]. This enables identification of tumor-specific niches and their characteristic signaling activities, potentially revealing new therapeutic targets.

The integration of advanced biomaterials, computational modeling, and high-resolution imaging is transforming our ability to study and manipulate stem cell niches in three dimensions. As research continues to illuminate how 3D microenvironments control stem cell fate, clinical applications will increasingly incorporate niche-informed strategies—from engineered tissue constructs that replicate native niche mechanics to therapeutic approaches that target pathological niche signaling [1]. Successful regenerative interventions must treat stem cells and their microenvironment as an inseparable therapeutic unit, marking a new era of microenvironmentally integrated medicine.

This document details the critical role of the three-dimensional (3D) microenvironment in cellular reprogramming, focusing on the biophysical transduction of mechanical cues into sustained epigenetic changes. Within realistic 3D cultures, mechanical stimuli—such as matrix stiffness, viscoelasticity, and spatial confinement—are sensed by cells and converted into biochemical signals that direct chromatin remodeling and gene expression. This application note provides a consolidated summary of quantitative data, standardized protocols for establishing physiological 3D microenvironments, and visualizations of the core mechano-epigenetic signaling pathways. The insights and methods herein are designed to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the tools to advance regenerative medicine and cancer research.

Quantitative Data in Mechano-Epigenetic Reprogramming

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent studies on how mechanical properties of the microenvironment influence cellular behavior and epigenetic states.

Table 1: Impact of Microenvironment Mechanics on Cell Fate and Reprogramming

| Mechanical Cue | Experimental System | Key Quantitative Finding | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate Stiffness | MSC culture on tunable substrates [8] | Long-term culture on stiff surfaces (≥20 kPa) leads to irreversible commitment to a specific lineage. | Establishes a "mechanical memory" that persists even after transferring cells to a soft substrate. |

| Viscoelasticity & Nonlinearity | Fibroblasts on tissue-mimicking IPN hydrogels [9] | Stiff IPN (15 mM Ca²⁺) promoted large mesenchymal aggregate formation (up to 100 μm diameter), unlike soft IPN (5 mM Ca²⁺) or linear elastic controls. | Aggregates showed elevated stemness genes and enhanced adipogenic/osteogenic differentiation potential. |

| 3D Spatial Localization | CLL B cells in 3D scaffold co-culture [10] | CLL B cells localized in the core of 3D structures showed significant upregulation of AP-1 transcription factor complex. | Core-localized cells exhibited significant protection against therapy-induced cell death (drug resistance). |

| Traction Forces | Mature vs. Developmental Tenocytes [11] | Mature tenocytes (40-45 weeks) exerted significantly higher traction stress and migrated ~50% faster than developmental tenocytes (4-4.5 weeks). | Increased contractility linked to transcriptomic shifts towards cytoskeletal and ECM gene expression. |

Table 2: Epigenetic Changes Driven by Mechanical Cues

| Epigenetic Marker | Experimental System | Quantitative Change | Associated Cellular State |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K27me3 (Repressive mark) | Mature Tenocytes [11] | Notable increase in mature tenocytes vs. developmental tenocytes. | Chromatin condensation, transcriptional repression, age-related functional shift. |

| H3K4me3 (Activating mark) | Mature Tenocytes [11] | Decrease in mature tenocytes vs. developmental tenocytes. | Reduced transcriptional activity of genes essential for tissue homeostasis. |

| Chromatin Condensation | Mature Tenocytes (STORM imaging) [11] | Significantly increased condensation in mature tenocytes. | Correlated with a more transcriptionally repressed state and altered mechanobiological function. |

| Histone Methylation (H3K9me3) | MSCs on stiff surfaces [8] | Altered distribution from nuclear lamina-associated to puncta form in late passages. | Associated with loss of cellular plasticity and establishment of mechanical memory. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing a 3D Scaffold-Based Co-Culture Model for Tumor Microenvironment Studies

This protocol, adapted from a CLL study [10], is ideal for investigating heterotypic cell-cell interactions and spatial heterogeneity in drug response.

- Key Applications: Modeling tumor-stromal-immune cell interactions; studying region-specific (core vs. periphery) drug resistance and epigenetic reprogramming.

Materials:

- Scaffolds: Alvetex scaffolds (200 μm thickness, 36-40 μm pore size).

- Stromal Cells: HS-5 human bone marrow-derived stromal cell line (or primary stromal cells).

- Primary Cells: Patient-derived primary cells (e.g., CLL B cells and autologous T cells).

- Coating: 0.1% gelatin solution.

- Culture Media: Appropriate for all cell types used (e.g., DMEM for HS-5, RPMI-1640 for PBMCs).

Methodology:

- Scaffold Preparation: Place the sterile scaffold in a suitable plate. Add 0.1% gelatin solution to cover the scaffold and incubate for 20 minutes at room temperature. Aspirate the gelatin.

- Stromal Seeding: Trypsinize and resuspend stromal cells (e.g., HS-5). Pipette 70 μL of cell suspension (density ~0.4 × 10⁶ cells/cm²) directly onto the center of the scaffold. Incubate for 1 hour at 37°C to allow cell attachment before carefully adding culture medium. Culture for 7 days to allow stromal cells to form a network.

- Primary Cell Seeding: Isolate and resuspend primary cells (e.g., PBMCs containing CLL and T cells). After 7 days, add the primary cell suspension (e.g., 2 × 10⁶ cells) to the scaffold and culture for an additional 4 days.

- Spatial Fractionation (Core vs. Periphery):

- Peripheral Cell Harvest: Gently rinse the scaffold 5-7 times in a spiral motion with PBS. Collect the entire supernatant, which contains the loosely attached "peripheral" population.

- Core Cell Harvest: After rinsing, physically cut the scaffold into small pieces. Place the pieces in PBS and agitate continuously at 250 rpm to dislodge the tightly embedded "core" population.

- Downstream Analysis: Isolated core and peripheral cells can be used for transcriptomic analysis (RNA-Seq), epigenetic profiling (ChIP-Seq for AP-1 factors or histone marks), and drug sensitivity assays.

Protocol 2: Fabricating and Utilizing Tissue-Mimicking Interpenetrating Network (IPN) Hydrogels for Mechanical Reprogramming

This protocol details the creation of hydrogels that replicate the key viscoelastic and nonlinear elastic properties of native tissues, enabling the study of mechanical reprogramming [9].

- Key Applications: Reprogramming of fibroblasts and cancer cells; enhancing stem cell differentiation potential; studying cell aggregation and mechanosensing.

Materials:

- IPN Components: Type I Collagen (e.g., from rat tail), Sodium Alginate.

- Cross-linker: Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) solution at varying concentrations (e.g., 5 mM and 15 mM).

- Buffers: Culture medium and PBS for dilution and neutralization.

Methodology:

- Hydrogel Precursor Preparation: Prepare the precursor solution by combining collagen (final conc. 1.5 mg/mL) and alginate (final conc. 10 mg/mL) in a neutral buffer or culture medium on ice to prevent premature collagen polymerization.

- Cross-linking: Add CaCl₂ solution to the collagen-alginate mixture to achieve the desired final concentration (e.g., 5 mM for "soft" or 15 mM for "stiff" IPNs). Mix gently and pipette the solution into the desired culture plates or molds.

- Gelation: Incubate the hydrogels at 37°C for 30 minutes to allow simultaneous collagen fibrillogenesis and calcium-mediated alginate cross-linking, forming a stable IPN.

- Cell Seeding and Culture: Seed cells (e.g., 3T3-L1 fibroblasts, MSCs, or cancer cells) directly onto the surface of the polymerized IPN hydrogels. Culture for several days, observing for morphological changes and aggregate formation.

- Functional Assays: Assess reprogramming outcomes via:

- Gene Expression: qPCR for stemness markers (e.g., Oct4, Sox2, Nanog) and lineage-specific genes.

- Differentiation Potential: Induce adipogenesis or osteogenesis and quantify differentiation efficiency.

- Cancer Reversion: Monitor epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) marker expression and oncogene downregulation.

Visualization of Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: Core Mechano-Epigenetic Signaling Pathway

This diagram illustrates the primary pathway through which external mechanical cues from the 3D microenvironment are transduced into sustained epigenetic changes and cellular reprogramming, integrating data from multiple sources [10] [11] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for 3D Mechano-Epigenetic Research

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Alvetex Scaffolds | Provides a porous 3D structure for studying spatially defined cell interactions and core-periphery effects. | Alvetex (Polystyrene, 200μm thick, 36-40μm pore size) [10] |

| Tissue-Mimicking IPN Hydrogel | Mimics the viscoelastic and nonlinear mechanical properties of native tissue for mechanical reprogramming studies. | Collagen-Alginate IPN (1.5 mg/mL Collagen I, 10 mg/mL Alginate, cross-linked with CaCl₂) [9] |

| YAP/TAZ Inhibitor | A chemical tool to inhibit the key mechanotransduction effectors YAP/TAZ, used to validate their role in the signaling pathway. | Verteporfin [12] [8] |

| ROCK Inhibitor | Inhibits Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) to disrupt actomyosin-mediated cellular contractility, a critical step in mechanotransduction. | Y-27632 [8] |

| H3K27me3-specific Antibody | For chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-Seq) or immunofluorescence to map/quantify this repressive histone mark. | Anti-H3K27me3 Rabbit Monoclonal Antibody [11] |

| EZH2 (PRC2) Inhibitor | A chemical inhibitor of the histone methyltransferase EZH2, used to probe the role of H3K27me3 in maintaining mechanical memory. | GSK126 [8] |

Accelerating Mesenchymal-to-Epithelial Transition (MET) Through Physical Cell Confinement

Within the field of cellular reprogramming, the Mesenchymal-to-Epithelial Transition (MET) is widely recognized as a critical, rate-limiting step for converting somatic cells, such as fibroblasts, into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [13]. This process involves a dramatic morphological and functional shift, where cells lose their migratory, elongated mesenchymal characteristics and adopt a polarized, cobblestone-like epithelial identity, a change essential for establishing pluripotency. However, the reprogramming process is inherently stochastic, with only a small fraction of cells successfully navigating this transition, thereby limiting efficiency and predictability for research and therapeutic applications [13]. Emerging evidence suggests that the biophysical properties of a cell's microenvironment are potent regulators of cell fate. This protocol details the application of a superhydrophobic microwell array chip (SMAR-chip) to impose defined physical confinement on cells, thereby providing a reproducible and highly efficient method to accelerate MET and enhance iPSC generation. This approach aligns with the growing consensus that three-dimensional microenvironments can significantly enhance reprogramming efficiency by more closely mimicking native tissue conditions and providing critical mechanical cues [3].

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential materials required for implementing this protocol.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| SMAR-Chip | A Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrate containing a 12x16 microwell array, surrounded by a non-adhesive superhydrophobic layer to confine cells and aggregates within the microwells [13]. |

| Doxycycline (DOX)-Inducible OSKM MEFs | Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts (MEFs) carrying a doxycycline-inducible polycistronic cassette for the expression of Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (Yamanaka factors) [13]. |

| Doxycycline | An antibiotic used to induce the expression of the reprogramming factors in the transgenic MEF system. |

| Fibrin-Based Hydrogel | A component for creating 3D tissue-engineered environments that enhance reprogramming; used here to illustrate the principle of 3D microenvironments [3]. |

| MMP Inhibitor (e.g., BB94/Batimastat) | A broad-spectrum pharmacological inhibitor used to investigate the role of Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP) activity in the reprogramming process [3]. |

| Antibodies for Immunostaining | Specific antibodies for detecting epithelial (E-cadherin) and mesenchymal (Vimentin, N-cadherin) markers, as well as pluripotency factors (Nanog, Oct4) [14] [13]. |

Methodological Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication and Preparation of the SMAR-Chip

- Fabrication: The SMAR-chip is composed of a PDMS substrate patterned with a 12 x 16 array of microwells. The top surface, excluding the microwells themselves, is grafted with a layer of superhydrophobic material [13].

- Sterilization: Prior to cell culture, sterilize the SMAR-chip using standard methods appropriate for PDMS (e.g., UV irradiation or ethanol treatment followed by rinsing with sterile phosphate-buffered saline).

- Assembly: Attach the sterilized SMAR-chip to the bottom of a standard 6-cm petri dish to facilitate routine cell seeding and media exchange.

Protocol 2: Cell Seeding and Reprogramming on the SMAR-Chip

- Cell Preparation: Isolate secondary MEFs from appropriate transgenic mice (e.g., R26rtTA; Col1a1 4F2A mice) carrying the inducible OSKM cassette. Seed the MEFs onto the SMAR-chip in standard fibroblast culture medium [13].

- Initiation of Reprogramming: Twenty-four hours after seeding, replace the medium with reprogramming medium supplemented with 2 µg/mL doxycycline to activate the expression of Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc.

- Culture Maintenance: Refresh the doxycycline-containing reprogramming medium every day. The non-adherent nature of the superhydrophobic material will confine the cells within the microwells, promoting the formation of 3D cell aggregates.

- Monitoring and Analysis: Monitor the emergence of compact, iPSC-like colonies, typically occurring between days 6 and 9 post-induction. The confined environment of the SMAR-chip directs these colonies to form specifically within the microwells, making their location predictable.

Protocol 3: Assessment of MET and Reprogramming Efficiency

Quantitative PCR (qPCR):

- Timeframe: Days 3-6 post-doxycycline induction.

- Method: Harvest cells from the SMAR-chip and control 2D cultures. Extract total RNA and synthesize cDNA.

- Targets: Analyze the expression of early epithelial markers (e.g., E-cadherin) and the downregulation of mesenchymal markers (e.g., Vimentin, N-cadherin). Subsequently, assess the expression of pluripotency genes such as Nanog and Oct4 [13].

Immunofluorescence Staining:

- Timeframe: Days 7-14.

- Method: Fix cells directly within the SMAR-chip microwells or in control wells. Perform immunostaining to visualize protein localization and expression.

- Key Markers:

Flow Cytometry:

- Timeframe: Day 14.

- Method: Dissociate cells into a single-cell suspension. Use a reporter cell line (e.g., αMHC-CFP for cardiac reprogramming or a Nanog-GFP reporter for pluripotency) to quantify the percentage of successfully reprogrammed cells via flow cytometry [3]. This provides a robust, quantitative measure of final reprogramming efficiency.

Key Data and Comparative Analysis

The following tables summarize the quantitative enhancements in reprogramming efficiency and molecular dynamics driven by physical confinement.

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of 3D Confinement on Reprogramming Efficiency

| Parameter | 2D Culture (Traditional) | 3D SMAR-Chip Culture | Notes / Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Efficiency | Low / Stochastic | ~6x higher than 2D | Bona fide colonies formed in ~90% of microwells [13]. |

| Cell Cycle Arrest | Prevalent | Overcome | 3D aggregates promoted re-entry into the cell cycle [13]. |

| MET Kinetics | Slower, Heterogeneous | Accelerated, Synchronized | Based on qPCR and immunostaining for E-cadherin and Vimentin [13]. |

| Epigenetic Modification | Baseline | Enhanced | Increased levels of histone H3 acetylation (AcH3) and H3K4me3 [13]. |

| Lineage Tracing (tdTomato+/cTnT+ cells) | Confirmed presence | Dramatically increased number | Using Fsp1-tdTomato reporter models [3]. |

Table 3: Molecular Dynamics in 2D vs. 3D Microenvironments

| Molecular Marker / Process | Response in 2D Culture | Response in 3D Confinement | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMP (e.g., MMP-2, MMP-3) Expression | Lower baseline | Strongly induced [3] | Cellular sensing of 3D geometry leading to cytoskeletal remodeling and MMP upregulation. |

| Early Cardiac TF Induction (Mef2C) | Standard induction | Significantly up-regulated at day 2 [3] | Enhanced activation of key transcriptional programs in a 3D context. |

| Effect of MMP Inhibition (BB94) | N/A | Abolished enhanced reprogramming [3] | MMP activity is necessary for the 3D environment's pro-reprogramming effect. |

| Tissue Stiffness | N/A | Lower in reprogrammed bundles [3] | Mirrors the shift from stiff fibrotic tissue to softer healthy myocardium. |

Signaling Pathway and Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the proposed mechanistic workflow through which physical confinement accelerates MET and enhances reprogramming.

Within the field of regenerative medicine, the three-dimensional (3D) microenvironment is increasingly recognized as a critical determinant of cell fate. This application note details a specific case study demonstrating that forcing fibroblasts into a 3D spheroid morphology alone, without genetic modification, is sufficient to reprogram them into a state exhibiting neural progenitor-like properties. This approach bypasses the tumorigenic risks associated with transgenic interventions and leverages biomechanical cues to initiate reprogramming, aligning with the broader thesis that the 3D microenvironment is a powerful tool for cellular reprogramming research [15].

The following workflow diagram outlines the key experimental and mechanistic stages of the 3D spheroid reprogramming process.

Case Study Details and Key Findings

A 2025 study provided direct evidence that neonatal mouse dermal fibroblasts (MDFs) can be reprogrammed into neural progenitor-like cells (NPCs) solely through 3D spheroid culture [15]. This process resulted in cells exhibiting neural cell-like properties and a significant functional capacity to promote neurite extension from dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons. Subsequent transplantation of these 3D spheroid MDFs into a rat model of sciatic nerve transection significantly accelerated nerve regeneration and improved motor function compared to transplantation of traditional 2D monolayer MDFs [15].

The following tables summarize the key quantitative findings from the in vitro and in vivo analyses.

Table 1: In Vitro Characterization of 3D Spheroid MDFs

| Parameter Investigated | Experimental Finding | Significance / Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Neurite Outgrowth | Significantly enhanced DRG neuron neurite extension in co-culture [15] | Demonstrates acquired bioinductive, pro-neural function |

| ID3 Protein Expression | Significantly upregulated in 3D spheroids [15] | Identified as a critical upstream regulator of reprogramming |

| HIF-1α Protein Expression | Significantly upregulated in 3D spheroids [15] | Indicates a hypoxic core in spheroids; synergizes with ID3 |

| Semaphorin7a Expression | Significantly upregulated by synergistic ID3/HIF-1α action [15] | Key axonal guidance protein mediating improved outcomes |

Table 2: In Vivo Functional Outcomes

| Assessment Model | Experimental Result | Functional Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Sciatic Nerve Transection (Rat) | Accelerated regeneration of the transected sciatic nerve [15] | Confirms therapeutic potential for peripheral nerve injury |

| Motor Function Analysis (Rat) | Improved motor function recovery post-transection [15] | Demonstrates translation of cellular changes to meaningful physiological repair |

Mechanism of Action

Mechanistic investigations revealed that the 3D spheroid culture induced a significant upregulation of the inhibitor of DNA binding 3 (ID3) and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) [15]. The study identified ID3 as a master regulator essential for the acquisition of neural progenitor-like properties. Furthermore, the upregulated ID3 and HIF-1α acted synergistically to increase the expression of the axonal guidance protein Semaphorin7a, which was identified as the key factor responsible for the observed enhancement of axon extension and nerve regeneration both in vitro and in vivo [15].

The signaling pathway below illustrates the molecular mechanism by which the 3D microenvironment drives reprogramming.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolation of Mouse Dermal Fibroblasts (MDFs)

Primary Cell Isolation:

- Collect dorsal skin tissues from neonatal C57BL/6 mouse.

- Remove subcutaneous tissues carefully and cut the remaining dermis into 1-2 cm² pieces.

- Digest overnight at 4°C with a medium containing 1 mg/mL dispase.

- The following day, separate and strip away the epidermis.

- Mince the isolated dermis and further digest with 0.25% collagenase I at 37°C for 1 hour with shaking.

- Pass the digested cell suspension through a 75 µm cell strainer, centrifuge, and resuspend the pellet in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin [15].

Expansion and Maintenance:

- Culture the isolated MDFs in standard tissue culture flasks.

- Use the above DMEM-based growth medium for all expansion and maintenance steps.

- Cells at the third passage are suitable for initiating 3D spheroid culture.

Protocol 2: 3D Spheroid Culture and Reprogramming

Preparation:

- Harvest MDFs from 2D culture using standard trypsinization.

- Count cells and prepare a suspension at the desired concentration.

3D Spheroid Formation:

- Seed 6 × 10⁶ MDFs into a 6-well ultra-low attachment plate. The use of ultra-low attachment surfaces is crucial to prevent cell adhesion and force aggregation.

- Do not change the culture media after seeding.

- Culture the cells at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 48 hours. Spheroids are typically fully formed and can be used for subsequent experiments at this time point [15].

Key Considerations:

- Do not disturb the culture during the initial 48-hour period to allow for stable spheroid formation.

- The same culture medium used for 2D expansion can be used for 3D spheroid culture.

Protocol 3: Functional Validation - Co-culture with DRG Neurons

DRG Neuron Isolation:

- Dissect bilateral lumbar DRGs from 10-week-old Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats.

- Cut DRGs into 1–2 mm pieces and incubate in a digestion medium (DMEM/Ham's F-12 with 1% collagenase XI) for 45 minutes at 37°C.

- Terminate digestion with DMEM containing 10% FBS.

- Triturate the tissue pieces gently in neuron culture medium (Neurobasal Medium supplemented with 2% B27, 2mM L-glutamine, and 1% P/S) to acquire a single-cell suspension [15].

Co-culture Setup:

- Seed 1 × 10⁴ monolayer or 3D spheroid MDFs (gently dissociated if needed) into a 0.1% gelatin-coated 24-well plate. Allow them to adhere for 24 hours.

- Replace the fibroblast culture medium with the neuron culture medium.

- Seed 5 × 10³ DRG neurons directly onto the fibroblast monolayer.

- Co-culture for 48 hours, then fix the cells with 4% polyoxymethylene for immunocytochemical analysis (e.g., staining with the neuronal marker Tuj1 to visualize and quantify neurite outgrowth) [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function / Application in the Protocol | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Low Attachment Plates | Prevents cell adhesion, forcing cells to aggregate into 3D spheroids. | 6-well format used for spheroid generation [15]. |

| Dispase | Enzymatic separation of the dermis and epidermis during primary fibroblast isolation. | Used at 1 mg/mL for overnight digestion at 4°C [15]. |

| Collagenase I | Further digestion of the isolated dermis to liberate individual fibroblasts. | Used at 0.25% for 1 hour at 37°C [15]. |

| Neurobasal Medium | A optimized base medium for maintaining low proliferation and high viability of post-mitotic neurons. | Used for DRG neuron culture and co-culture experiments [15]. |

| B27 Supplement | A serum-free supplement essential for the long-term survival of neurons in culture. | Added to Neurobasal Medium at 2% concentration [15]. |

| Antibody: Tuj1 (βIII-Tubulin) | Immunocytochemical marker for mature neurons; used to stain and quantify neurite outgrowth in co-culture. | Standard marker for neuronal morphology [15]. |

Protocols and Progress: Implementing 3D Reprogramming for Specific Cell Lineages

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a dynamic, complex network that provides far more than just structural support to cells; it serves as a critical signaling hub that actively orchestrates cellular behavior and fate [16] [17]. In the context of cellular reprogramming, the three-dimensional microenvironment presents a powerful, yet often underexploited, tool for enhancing the efficiency and quality of cell fate conversion [18]. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) culture systems fail to recapitulate the intricate biophysical and biochemical cues that cells experience in vivo, often resulting in incomplete maturation and functionality of reprogrammed cells [18] [19]. This application note details the design principles, fabrication protocols, and characterization methods for creating engineered matrices and scaffolds that mimic native ECM properties to optimize the 3D extracellular environment for cellular reprogramming research and therapeutic applications.

The paradigm is shifting from considering biomaterials as passive cell carriers to designing them as active instructors of cellular behavior [20]. By precisely controlling scaffold properties—including mechanical stiffness, architectural topology, and biochemical composition—researchers can create microenvironments that significantly enhance direct reprogramming outcomes. For instance, recent studies demonstrate that decellularized heart ECM in a 3D hydrogel format improves chemically induced direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes, yielding cells with more mature structural and functional characteristics compared to those reprogrammed in conventional 2D formats [18]. Similarly, scaffolds with aligned microchannels have shown remarkable capabilities in guiding spatial organization and enhancing maturation of various cell types, including muscle, nerve, and vascular cells [21].

Scaffold Design Principles for Reprogramming Microenvironments

Recapitulating Native Extracellular Matrix Properties

The optimal engineered scaffold must replicate key aspects of the native ECM to successfully direct cellular reprogramming. Four fundamental design principles guide this process:

Biomimetic Architecture: Create three-dimensional structures with tissue-specific porosity and topography that enable cell migration, nutrient diffusion, and spatial organization [17] [21]. The scaffold should feature interconnected pores with diameters appropriate for the target tissue (typically 50-200μm) to facilitate cell infiltration and vascularization [22].

Mechanical Competence: Match the elastic modulus (stiffness) of the target tissue, as this parameter profoundly influences stem cell differentiation and reprogramming efficiency [23] [17]. For example, soft matrices (∼1 kPa) promote neuronal differentiation, while stiffer matrices (10-20 kPa) favor myogenic differentiation, and rigid substrates (>30 kPa) enhance osteogenic commitment [23].

Biochemical Signaling: Incorporate tissue-specific ECM components (collagens, laminins, fibronectin) and controlled-release mechanisms for growth factors that guide reprogramming [17] [20]. Decellularized ECM scaffolds retain tissue-specific matrisome proteins that significantly enhance reprogramming efficiency compared to generic matrices like Matrigel [18].

Dynamic Responsiveness: Implement scaffolds capable of temporal evolution in their properties to match different stages of the reprogramming process, from initial fate commitment to functional maturation [24]. This includes designing materials with controlled degradation profiles that synchronize with new matrix deposition by the reprogrammed cells [21].

Material Selection for Reprogramming Scaffolds

Table 1: Biomaterial Options for Engineering Reprogramming Microenvironments

| Material Category | Key Examples | Advantages | Limitations | Reprogramming Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers | Collagen, Fibrin, Hyaluronic Acid, Laminin | Innate bioactivity, inherent cell adhesion motifs, natural degradation products | Batch-to-batch variability, limited mechanical strength, potential immunogenicity | Cardiac reprogramming [18], Neural reprogramming [19] |

| Decellularized ECM | Heart ECM, Liver ECM, Brain ECM | Tissue-specific biochemical composition, preserved structural complexity, endogenous growth factors | Potential residual DNA content, complex sterilization requirements, source-dependent properties | Enhanced cardiac reprogramming [18], Muscle regeneration [21] |

| Synthetic Polymers | PLGA, PEG, PCL, Self-assembling peptides | Precise control over properties, reproducible manufacturing, tunable degradation | Lack of innate bioactivity, potential inflammatory degradation products | Customizable platforms for reprogramming [23] [24] |

| Hybrid Materials | PEG-collagen, Peptide-functionalized PLGA | Combines bioactivity with mechanical control, customizable degradation profiles | Complex fabrication, potential interface issues | Advanced reprogramming systems with spatial control [17] |

Experimental Protocols for Scaffold Fabrication and Application

Protocol 1: Preparation of Decellularized Heart ECM Hydrogel for Cardiac Reprogramming

This protocol describes the methodology for creating heart ECM-derived hydrogels that have demonstrated significant enhancement in chemical reprogramming of fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes [18].

Materials and Reagents:

- Heart tissue (porcine or murine)

- Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution (0.5-1%)

- Triton X-100 (1%)

- DNase/RNase solution

- Pepsin solution (0.1M HCl)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Neutralization solution (0.1M NaOH + 10× PBS)

Procedure:

- Tissue Decellularization:

- Rinse heart tissue thoroughly in PBS to remove blood components.

- Cut tissue into 1-2mm sections using a surgical blade.

- Treat tissue with 0.5% SDS solution for 4-6 hours with constant agitation.

- Rinse with 1% Triton X-100 for 2 hours to remove residual SDS.

- Incubate with DNase/RNase solution (50U/mL in PBS) for 3 hours at 37°C to remove nucleic acids.

- Validate decellularization by measuring DNA content (<50ng/mg dry weight) [18].

- ECM Solubilization and Hydrogel Formation:

- Minced decellularized tissue in 0.1M HCl containing 1mg/mL pepsin at a ratio of 10mg tissue per 1mL solution.

- Stir continuously for 48-72 hours at room temperature until completely dissolved.

- Neutralize the pre-gel solution using neutralization solution (10% v/v) and maintain on ice.

- Adjust protein concentration to 8-12mg/mL using PBS.

- Incubate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes to form hydrogel.

Quality Control:

- Perform proteomic analysis to verify retention of key matrisome proteins (collagens VI and XI, elastin, fibronectin) [18].

- Confirm absence of cellular remnants via DAPI staining and histological analysis.

- Assess gelation kinetics using rheometry.

Protocol 2: In Vivo Engineered ECM Scaffolds with Aligned Microchannels

This advanced protocol creates ECM scaffolds with instructive parallel microchannels that guide cell organization and enhance tissue maturation [21].

Materials and Reagents:

- Polycaprolactone (PCL) microfibers (diameter: 141.8 ± 5.2μm)

- Surgical tools for subcutaneous implantation

- SDS and Triton X-100 solutions

- DNase/RNase solution

- Cell culture reagents for in vitro assessment

Procedure:

- Template Fabrication and Implantation:

- Create aligned PCL microfiber membranes (thickness: 1.5mm) using electrospinning or melt-spinning techniques.

- Sterilize templates via ethylene oxide or ethanol immersion.

- Surgically implant templates into rat subcutaneous pockets for 4 weeks to allow cellular infiltration and ECM deposition.

- ECM Scaffold Generation:

- Harvest tissue-embedded templates after 4 weeks.

- Remove PCL microfibers by immersion in organic solvents (e.g., acetone or chloroform) with agitation.

- Decellularize using a combination of 0.5% SDS and DNase/RNase treatment.

- Validate complete PCL removal using gel permeation chromatography [21].

Characterization:

- Verify aligned microchannel structure (diameter: 146.6 ± 6.9μm) using scanning electron microscopy.

- Assess porosity (target: 74.4 ± 2.1%) and anisotropy (target: 0.89 ± 0.12) using microCT scanning.

- Confirm retention of ECM components (collagen, elastin, sGAG) through biochemical assays and histology.

Protocol 3: 3D Reprogramming in Engineered Microenvironments

This application protocol describes the process for implementing reprogramming protocols within optimized 3D environments.

Materials and Reagents:

- Fabricated scaffolds (decellularized ECM hydrogels or ECM-C scaffolds)

- Source cells (typically fibroblasts for direct reprogramming)

- Reprogramming factors (small molecules or gene delivery systems)

- Cell culture medium appropriate for target cell type

- Analytical reagents for assessment (antibodies, PCR reagents, electrophysiology equipment)

Procedure:

- 3D Cell Seeding:

- For hydrogel systems: Suspend cells in pre-gel solution at desired density (1-5 × 10^6 cells/mL) and plate followed by gelation at 37°C.

- For pre-formed scaffolds: Seed cells dropwise onto scaffolds and allow attachment for 4-6 hours before adding medium.

Reprogramming Induction:

- Initiate reprogramming 24 hours after seeding using established chemical cocktails or gene delivery methods.

- For cardiac reprogramming: Use reported small molecule combinations (e.g., CHIR99021, RepSox, Forskolin, VPA) [18].

- Maintain cultures with medium changes every 2-3 days.

Functional Maturation:

- After initial reprogramming (7-14 days), switch to maturation media containing appropriate factors (e.g., T3 hormone for cardiomyocytes).

- For electrically excitable cells, consider applying electrical stimulation or mechanical conditioning to enhance maturation.

Assessment Methods:

- Track reprogramming efficiency via immunostaining for cell-specific markers at multiple time points.

- Assess functional maturity: calcium transients and electrophysiology for cardiomyocytes [18], synaptic activity for neurons.

- Evaluate structural organization via confocal microscopy and analysis of sarcomeric organization (cardiomyocytes) or process extension (neurons).

Signaling Pathways in ECM-Mediated Reprogramming

The extracellular microenvironment influences cellular reprogramming through several key signaling pathways that are activated by cell-ECM interactions. The following diagram illustrates the major signaling mechanisms through which engineered matrices influence cellular reprogramming:

The mechanical properties of the scaffold, particularly substrate stiffness, directly influence cytoskeletal tension and subsequent YAP/TAZ signaling—a critical mechanotransduction pathway that regulates cell fate decisions [23] [17]. Simultaneously, integrin engagement with scaffold-bound ligands initiates FAK phosphorylation, which activates multiple downstream pathways including MAPK/ERK for proliferation and differentiation, and PI3K/Akt for cell survival [24]. The convergence of these signaling cascades ultimately determines the efficiency and quality of cellular reprogramming, highlighting how engineered matrices can actively instruct rather than passively support cell fate conversion.

Quantitative Characterization of Engineered Microenvironments

Critical Parameters for Reprogramming Scaffolds

Table 2: Key Characterization Parameters for Reprogramming Scaffolds

| Parameter Category | Specific Measurements | Optimal Range for Reprogramming | Analytical Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Properties | Porosity | 70-90% [21] | MicroCT scanning, SEM analysis |

| Pore Size/Channel Diameter | 100-200μm (cell infiltration), 146.6 ± 6.9μm (aligned channels) [21] | SEM, histological sectioning | |

| Fiber Diameter | 0.5-5μm (nanofibrous scaffolds) | SEM, TEM | |

| Mechanical Properties | Elastic Modulus | Tissue-specific: ~1kPa (neural), 10-20kPa (muscle), >30kPa (bone) [23] | Atomic force microscopy, rheometry |

| Tensile Strength | Sufficient for surgical handling (>0.69N for suture retention) [21] | Uniaxial tensile testing | |

| Degradation Profile | Matches tissue formation rate (weeks to months) | Mass loss measurements, GPC | |

| Biochemical Composition | DNA Content (decellularized) | <50ng/mg dry weight [18] [21] | DNA quantification assays |

| Collagen Content | Tissue-specific retention (>50% of native) [18] | Hydroxyproline assay, Sirius red staining | |

| GAG Content | Tissue-specific retention | Alcian blue staining, DMMB assay | |

| Growth Factor Retention | Varies by application | ELISA, proteomic analysis | |

| Biological Performance | Reprogramming Efficiency | Significant enhancement over 2D controls [18] | Flow cytometry, immunostaining quantification |

| Functional Maturation | Enhanced sarcomeric organization, electrophysiological properties [18] | Confocal microscopy, patch clamping, calcium imaging |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ECM Engineering and Reprogramming

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reprogramming | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decellularization Agents | SDS (0.5-1%), Triton X-100 (1%), CHAPS | Remove cellular material while preserving ECM structure and composition | SDS effectively removes DNA but may damage ECM; Triton X-100 is gentler but less efficient; often used in combination [17] [18] |

| Enzymatic Modifiers | Pepsin, Trypsin, DNase/RNase, MMP inhibitors | Solubilize ECM, remove nucleic acid remnants, control ECM degradation | Pepsin digestion under acidic conditions solubilizes ECM for hydrogel formation [18]; MMP inhibitors control scaffold degradation rate |

| Natural Polymer Scaffolds | Collagen I, Fibrin, Laminin, Hyaluronic Acid | Provide innate bioadhesive properties and biochemical cues | Collagen I supports broad cell types; laminin enhances neural and epithelial reprogramming [20] |

| Synthetic Polymers | PLGA, PEG, PCL, Self-assembling peptides | Offer controlled mechanical properties and customizable functionality | PEG can be modified with RGD peptides to enhance cell adhesion [24]; PCL provides structural stability [21] |

| Functionalization Agents | RGD peptides, IKVAV peptides, Growth factors (FGF, VEGF, TGF-β) | Enhance cell adhesion, promote specific differentiation pathways | RGD peptides engage integrins αvβ3 and α5β1 to promote cell adhesion and survival [24] |

| Reprogramming Cocktails | Small molecules (CHIR99021, RepSox, Forskolin), Transcription factors, miRNAs | Induce cell fate conversion | 3D environments enhance efficiency of both chemical and genetic reprogramming approaches [18] [19] |

Engineered matrices and scaffolds represent a transformative approach in cellular reprogramming research, moving beyond passive support systems to active instructors of cell fate. The protocols and design principles outlined in this application note provide researchers with practical methodologies for creating 3D microenvironments that significantly enhance reprogramming outcomes. Key advances include the use of tissue-specific decellularized ECM to provide appropriate biochemical cues [18], the incorporation of aligned microarchitectures to guide tissue organization [21], and the precise control of mechanical properties to direct lineage specification [23] [17].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on creating even more dynamic and responsive scaffold systems that can adapt their properties in real-time to guide different stages of the reprogramming process. The integration of advanced fabrication technologies such as 3D bioprinting will enable creation of complex, heterogenous tissue structures with regional variations in ECM composition and mechanical properties [16] [25]. Additionally, the incorporation of biosensors within scaffolds to monitor reprogramming progress and the development of closed-loop systems that adjust scaffold properties based on cell behavior represent exciting frontiers in smart biomaterial design for regenerative medicine applications.

As these technologies mature, standardized characterization of scaffold properties—as detailed in the quantitative tables provided—will be essential for comparing results across studies and advancing the field. By systematically applying these engineering principles to the design of reprogramming microenvironments, researchers can overcome current limitations in reprogramming efficiency and functional maturation, accelerating progress toward therapeutic applications.

Direct reprogramming of somatic cells into induced neurons (iNs) holds promise for disease modeling and regenerative therapy. However, conventional two-dimensional (2D) cultures face limitations in neuronal maturity, survival, and post-transplantation integration. This protocol details a robust method for reprogramming adult human dermal fibroblasts (hDFs) into functional iNs within three-dimensional suspension microcultures (3D-iNs). The 3D microenvironment enhances neuronal identity, functional maturation, and graft survival in vivo, addressing critical bottlenecks in translational applications [26] [27] [28].

The 3D reprogramming platform leverages cell-cell interactions and spatial confinement to promote epigenetic remodeling and neuronal commitment. Compared to 2D systems, 3D-iNs exhibit improved transcriptional profiles, extended viability, and successful integration into host brain circuits post-transplantation [27]. This protocol aligns with the broader thesis that 3D microenvironments are critical for mimicking physiological conditions in cellular reprogramming research.

Table 1: Key Metrics of 3D-iNs vs. 2D-iNs

| Parameter | 3D-iNs | 2D-iNs |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Efficiency | 39.8–49.5% MAP2+ cells [27] | ~20–30% (literature estimates) |

| Culturing Span | Extended (>30 days) [27] | Limited (<21 days) [26] |

| Graft Survival | Neuron-rich grafts in rodent brains [27] | Poor survival post-transplantation [26] |

| Neuronal Subtypes | Primarily GABAergic (GAD65/67+) [27] | Heterogeneous subtypes |

Table 2: Transcriptomic Analysis of 3D Reprogramming

| Time Point | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Day 2 | Initiation of fibroblast-to-neuron transcriptional shift [27] |

| Day 7 | Upregulation of neuronal genes (e.g., MAP2, GAD2) [27] |

| Day 21 | Clear separation from fibroblast identity via PCA [27] |

Experimental Workflow

The diagram below outlines the core 3D reprogramming protocol:

Detailed Protocols

3D Microculture Setup and Reprogramming

Materials:

- Source hDFs: Adult human dermal fibroblasts (e.g., from patient biopsies) [27].

- Lentiviral Vectors: All-in-one construct expressing Ascl1, Brn2, and shRNA against REST [27].

- Microwell Array: Conical ultralow-attachment plates (e.g., AggreWell) [27].

- Media:

Steps:

- Cell Preparation: Mix hDFs with lentivirus (MOI = 5–10) in suspension.

- Seeding: Transfer 250–4,000 cells/microwell into pre-chilled arrays. Centrifuge at 500 × g for 10 min.

- Culture:

- Days 0–14: Maintain in induction medium at 37°C/5% CO₂.

- Days 14–30: Replace with maturation medium, half-changed twice weekly.

- Harvesting: Gently pipette microspheres without enzymatic dissociation.

Functional Validation

- Immunostaining: Fix 3D-iNs and stain for MAP2 (mature neurons), TAU (axonal markers), and GAD65/67 (GABAergic identity) [27].

- Electrophysiology: Perform patch-clamping to confirm action potentials and synaptic currents [27].

- Transplantation: Inject 3D-iNs into rodent striatum using glass capillaries. Monitor graft survival via histology at 4–12 weeks [27].

Signaling Pathways in 3D Reprogramming

The 3D microenvironment activates critical signaling cascades for neuronal maturation:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for 3D-iN Generation

| Reagent | Function | Example Product |

|---|---|---|

| Ultralow-Attachment Plates | Enables self-assembly of microspheres | AggreWell (STEMCELL Technologies) |

| Lentiviral Vectors | Delivery of reprogramming factors (Ascl1, Brn2, shREST) | Custom all-in-one constructs [27] |

| Neurobasal-A Medium | Base for neuronal induction and maturation | Gibco Neurobasal-A |

| B27 Supplement | Supports neuronal survival and differentiation | Gibco B27-VA |

| BDNF/GDNF/NT-3 | Promotes neuronal maturation and synaptic plasticity | PeproTech recombinant proteins |

| Anti-MAP2 Antibody | Validation of neuronal identity via immunostaining | Abcam #ab5392 |

This protocol demonstrates that 3D suspension microcultures overcome key limitations of 2D reprogramming by enhancing neuronal conversion, functionality, and translational utility. The platform is scalable for high-throughput drug screening and personalized regenerative medicine [26] [27].

The study of liver biology and the development of treatments for liver diseases have been historically constrained by the limitations of traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell culture systems and animal models. Two-dimensional cultures fail to mimic the complex three-dimensional (3D) architecture and cellular heterogeneity of the liver, while animal models are limited by inter-species differences and ethical considerations [29] [30]. The emergence of 3D human cell culture systems, particularly organoids, presents a transformative solution. Organoids are 3D structures that recapitulate aspects of native tissue architecture and function in vitro through self-organization of cells [31].

This application note provides a detailed protocol for generating complex hepatic organoids starting from human fibroblasts. We outline a methodology for reprogramming fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), directing their differentiation through key hepatic lineages, and co-culturing them with supporting cell types in a 3D matrix to form vascularized liver organoids. This model replicates the in vivo liver microenvironment more accurately than previous systems, providing a powerful platform for disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine [32] [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following tables catalog the essential reagents, factors, and culture systems required for the successful generation of hepatic organoids.

Table 1: Key Reagents for Fibroblast Reprogramming and Hepatic Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (Yamanaka factors) [33]; LIN28 [33] | Reprogram somatic fibroblasts to a pluripotent state (iPSCs) |

| Reprogramming Method | mRNA Transfection [33]; Sendai Virus [33]; Small Molecules [33] | Non-integrating delivery of reprogramming factors |

| Signaling Pathway Agonists | CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor) [31] | Activates Wnt pathway for progenitor expansion |

| Signaling Pathway Antagonists | A83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor) [31] | Inhibits differentiation-promoting TGF-β signaling |

| Growth Factors | Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) [30]; Fibroblast Growth Factors (FGF7, FGF10, FGF-basic) [30] [31]; Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) [31] | Promote hepatic endoderm specification, progenitor expansion, and maturation |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Matrigel [30]; Synthetic PEG Hydrogels [30] | Provides a 3D scaffold that mimics the native stem cell niche |

Table 2: Core Cell Culture Media Formulations

| Media Type | Base | Critical Supplements | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Media | As per mRNA/method protocol | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC mRNAs [33] | Supports conversion of fibroblasts to iPSCs |

| Definitive Endoderm (DE) Media | DMEM/F12 | Activin A, Wnt3a [33] | Directs iPSCs toward definitive endoderm lineage |

| Hepatic Progenitor Expansion Media | AdDMEM/F12 [31] | N2/B27 supplements [31], N-Acetylcysteine [31], R-Spondin-1 [32], EGF, FGF10 [31], A83-01 [31], CHIR99021 [31] | Supports long-term expansion of bipotent liver progenitors |

| Hepatic Maturation Media | DMEM/F12 or similar | Oncostatin M, Dexamethasone [30] | Promotes terminal differentiation into functional hepatocytes |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Reprogramming of Human Fibroblasts to iPSCs

This protocol describes a non-integrating mRNA-based method for generating iPSCs, which minimizes the risk of insertional mutagenesis and provides high reprogramming efficiency [33].

- Cell Source: Obtain human dermal fibroblasts from a commercial source or tissue biopsy.

- Culture and Expansion: Maintain fibroblasts in standard fibroblast growth medium. Passage as needed until a sufficient number of cells (e.g., 1x10^5) are available for reprogramming.

- mRNA Transfection: Transfect fibroblasts with synthetic mRNAs encoding the reprogramming factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, and optionally LIN28) using a commercially available mRNA transfection kit. Repeat transfections every other day for approximately 2-3 weeks [33].

- iPSC Colony Picking: Between days 21-28, identify and manually pick embryonic stem cell-like colonies exhibiting tight borders and high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratios.

- Expansion and Validation: Expand picked colonies on a feeder layer or in feeder-free conditions. Validate successful reprogramming through analysis of pluripotency markers (e.g., NANOG, TRA-1-60) by immunocytochemistry and/or RT-qPCR. Karyotype analysis is recommended to confirm genomic stability.

Protocol 2: Directed Hepatic Differentiation of iPSCs

This multi-stage protocol guides iPSCs through developmental steps to form functional hepatocyte-like cells [33].

Definitive Endoderm (DE) Differentiation:

- Culture iPSCs to 80-90% confluence.

- Replace medium with DE induction medium containing Activin A (100 ng/mL) and Wnt3a (50 ng/mL) for 3-5 days.

- Quality Control: Confirm efficient DE differentiation by verifying that >80% of cells express DE markers (SOX17, FOXA2) via flow cytometry.

Hepatic Progenitor Specification:

- Following DE formation, switch to hepatic specification medium containing BMP-4 and FGF-basic for 5-7 days.

- Cells should transition into a hepatic endoderm state, expressing markers like HNF4A and AFP.

Hepatoblast Expansion:

- Dissociate the hepatic endoderm cells into a single-cell suspension.

- Embed the cells in droplets of Matrigel or a synthetic PEG-based hydrogel and culture with hepatic progenitor expansion media (see Table 2).

- Over 7-14 days, the cells will self-organize into 3D structures. These can be passaged every 2-3 weeks by mechanical/enzymatic dissociation and re-embedding in matrix [30].

Hepatocyte Maturation:

- Transfer the expanded progenitor organoids to hepatic maturation media containing Oncostatin M and Dexamethasone for 10-14 days.

- Functional Validation: Assess maturity by measuring albumin and urea production in the supernatant, analyzing cytochrome P450 activity, and staining for hepatic markers (ALB, HNF4A, AAT) [30] [32].

Protocol 3: Generation of a Multiple-Cell Microenvironment Organoid

To enhance physiological relevance, this protocol incorporates stromal and endothelial cells to create a vascularized liver organoid model [32] [33].

Cell Preparation:

- Generate iPSC-derived hepatic endoderm cells (iPSC-HEs) as described in Protocol 2, Step 3.

- Acquire human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) and Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs).

Cell Aggregation:

- Combine the three cell types (iPSC-HEs, MSCs, HUVECs) in a defined ratio (e.g., 5:3:2) in a low-adhesion U-bottom plate.

- Centrifuge the plate gently to encourage aggregate formation.

3D Culture and Maturation:

- After 24-48 hours, transfer the self-assembled cellular aggregates onto a pre-solidified bed of Matrigel or a synthetic hydrogel.

- Culture the organoids in a mixture of hepatic maturation media and endothelial cell media to support all cell types.

- Within 5-10 days, the organoids will form complex, vascularized structures that exhibit improved morphological organization and liver-specific function compared to single-cell-type organoids [32].

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core experimental workflow and the key signaling pathways governing cell fate.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for generating vascularized liver organoids.

Diagram 2: Key signaling pathways in hepatic organoid development.

Theoretical Foundation: The Role of the 3D Microenvironment in Direct Reprogramming

Direct reprogramming, or transdifferentiation, represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine by enabling the conversion of somatic cells directly into a target cell lineage, bypassing an intermediate pluripotent stem cell state. This approach offers significant advantages, including reduced tumorigenic risk, increased efficiency, and faster processing times compared to induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-based methods [34] [35]. The success of this process is profoundly influenced by the cellular microenvironment. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cultures lack the necessary tissue architecture, cellular organization, and cell-to-cell interactions found in vivo [36].

The transition to three-dimensional (3D) organoid culture systems has been a critical advancement. These systems provide a biomimetic environment that more accurately replicates the biochemical and biomechanical cues of native tissue, supporting complex cellular behaviors such as self-organization and spatial differentiation [36] [37]. For reprogramming somatic cells into pulmonary alveolar epithelial-like cells (iPULs), the 3D microenvironment is not merely supportive but essential, as it facilitates the structural organization and functional maturation necessary for a successful cell fate conversion [38].

iPUL Generation Protocol: From Mouse Fibroblasts to Alveolar Epithelial-like Cells

The following diagram illustrates the core process for generating iPULs from mouse fibroblasts, combining transcription factor reprogramming with a 3D culture system.

Detailed Stepwise Protocol

Step 1: Transcription Factor Screening and Selection

- Objective: Identify the minimal combination of transcription factors sufficient to induce an alveolar epithelial cell fate.

- Initial Candidate Pool: 14 genes known to be associated with lung development were screened: Nkx2-1, Foxa1, Foxa2, Foxj1, Tcf21, Hoxa5, Sox17, Gata6, Tbx4, Gata5, Foxf1, Foxl1, Gli2, and Gli3 [38].

- Screening Method:

- Transduce mouse tail-tip fibroblasts (TTFs) with a mixture of retrovirus vectors carrying all 14 genes.

- Culture transduced cells in 2D dishes for 7 days.

- Assess induction of the AT2 cell marker Surfactant Protein-C (Sftpc) by systematically omitting one factor at a time.

- Outcome: Omission of Nkx2-1 drastically reduced Sftpc expression. The most potent combination for inducing Sftpc was found to be four transcription factors (4TFs): Nkx2-1, Foxa1, Foxa2, and Gata6 [38].

Step 2: Cell Source Preparation and Transduction

- Recommended Cell Sources:

- Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts (MEFs) isolated from Sftpc-GFP reporter mice.

- Mouse Tail-tip Fibroblasts (TTFs).

- Mouse Dermal Fibroblasts (MDFs).

- Procedure:

- Isolate and expand fibroblasts using standard tissue culture techniques.

- Using retroviral vectors, transduce fibroblasts with the 4TFs (Nkx2-1, Foxa1, Foxa2, Gata6).

- Confirm transduction efficiency; approximately 80% of cells should be DsRed-positive 3 days post-transduction [38].

Step 3: 3D Organoid Culture and Enhanced Reprogramming

- Rationale: Switching from 2D to 3D organoid culture significantly improves reprogramming efficacy by providing a physiologically relevant microenvironment [38] [36].

- Culture Setup:

- After transduction, embed cells in a suitable 3D matrix such as Matrigel or tunable synthetic hydrogels [37].

- Culture cells in a defined, serum-free medium supplemented with:

- Timeline and Observations:

- Over 7 days, transduced MEFs gradually lose the fibroblast marker Vimentin (Vim).

- Organoids emitting Sftpc-GFP fluorescence will form, indicating successful reprogramming toward an AT2-like fate [38].

Step 4: Isolation and Purification of iPULs

- Marker Profile for Sorting:

- Positive: Sftpc-GFP (AT2 cell marker), EpCAM (epithelial cell adhesion marker).

- Negative: Thy1.2 (fibroblast marker).

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) Protocol:

- Harvest organoids between day 7 and 10 post-transduction.

- Dissociate organoids into single-cell suspension using enzymatic digestion (e.g., TrypLE).

- Resuspend cells in FACS buffer and sort for the population: Sftpc-GFP+ / Thy1.2- / EpCAM+.

- Expected Outcome: This sorted population, designated iPULs, typically constitutes 2-3% of all cells on day 7 [38]. These purified iPULs can be expanded and maintained through several passages while retaining key characteristics.

Key Quantitative Data from Reprogramming

The tables below summarize the critical quantitative findings from the iPUL generation protocol.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Outcomes of iPUL Generation and Characterization

| Parameter | Result | Context / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Efficiency (2D) | 0.002% ± 0.0004% | Sftpc-positive colonies from TTFs with 4TFs [38]. |

| Reprogramming Efficiency (3D) | ~34% | Sftpc-GFP+ Thy1.2- cells from MEFs at day 7 [38]. |

| Final iPUL Yield | 2-3% | Sftpc-GFP+ Thy1.2- EpCAM+ cells after FACS [38]. |

| Sftpc Expression Fold-Change | ~1000x | In Adult Lung Fibroblasts (ALFs) at day 7 vs. control (qPCR) [38]. |

Table 2: In Vivo Functional Validation of iPULs

| Assay | Model | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Intratracheal Administration | Bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis mouse model | iPULs integrated into the alveolar surface and formed both AT1-like and AT2-like cells in vivo [38]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful replication of this protocol requires the following key reagents and solutions.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for iPUL Generation

| Item | Function / Role | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factors | Master regulators of alveolar cell fate conversion. | Nkx2-1, Foxa1, Foxa2, Gata6 (delivered via retroviral vectors) [38]. |

| 3D Culture Matrix | Provides a scaffold for 3D organoid formation and biomechanical cues. | Matrigel; or advanced alternatives like tunable synthetic hydrogels (e.g., gelatin methacrylate) for reduced variability [37]. |

| Signaling Molecules | Enhances reprogramming efficiency and directs cell fate. | Wnt activators (e.g., CHIR99021), Growth Factors (KGF, FGFs), SMAD inhibitors (SB431542, Dorsomorphin) [38]. |

| FACS Antibodies | Enables isolation of pure iPUL population based on surface and reporter markers. | Anti-Thy1.2, Anti-EpCAM; relies on Sftpc-GFP reporter expression [38]. |

| Serum-Free Media | Defined culture conditions to support reprogrammed epithelial cells. | Base media (e.g., DMEM/F12) supplemented with N2, B27, and other specific factors [38]. |

Characterization and Functional Validation of iPULs

In Vitro Characterization

- Transcriptomic Analysis: RNA sequencing confirmed that iPULs present an AT2-like transcriptome, expressing key genes characteristic of alveolar epithelial type 2 cells [38].

- Morphological Assessment: Transmission electron microscopy can be used to identify the presence of lamellar body-like structures, which are secretory organelles unique to AT2 cells [38].

- Self-Renewal Capacity: Purified iPULs sorted via FACS can form new organoids upon passaging, demonstrating self-renewal capability similar to primary AT2 cells [38].

In Vivo Functional Validation

The ultimate validation of iPUL function involves testing their ability to integrate into injured lung tissue and contribute to repair.

- Procedure:

- Use a well-established mouse model of lung injury, such as the bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis model.

- Administer iPULs via intratracheal instillation.

- After a suitable period (e.g., 1-2 weeks), analyze lung tissues.

- Expected Outcome: The administered iPULs integrate into the damaged alveolar walls. Notably, they demonstrate plasticity by differentiating into both alveolar epithelial type 1 (AT1)-like cells and AT2-like cells in vivo, contributing to the restoration of the alveolar epithelium [38].

Concluding Remarks

The direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into self-renewable iPULs using a defined set of transcription factors combined with a 3D organoid culture system represents a significant breakthrough in pulmonary regenerative medicine. This protocol successfully generates a cell population with key molecular and functional features of alveolar epithelial cells, capable of integrating into injured lung tissue in vivo. The reliance on a 3D microenvironment underscores its critical role in facilitating complete cellular reprogramming and functional maturation. This technology holds great promise for developing novel cell-based therapies for intractable lung diseases such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and provides a powerful new platform for disease modeling and drug screening.

The pursuit of personalized medicine has created a paradigm shift in cellular reprogramming research, moving away from one-size-fits-all models toward patient-specific therapeutic strategies. Central to this shift is the ability to recreate the native three-dimensional (3D) microenvironment, which is critical for maintaining cellular functions and responses that accurately mimic human physiology [39]. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures and animal models have significant limitations; 2D cultures lack crucial cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions [39] [40], while animal models suffer from interspecies differences that limit their predictive value for human outcomes [41]. These limitations contribute to the staggering 90% failure rate of drug candidates during clinical development [42].

3D bioprinting emerges as a transformative technology that addresses these challenges by enabling the precise, spatially controlled deposition of cells, biomaterials, and biological factors to create complex, patient-specific tissue constructs [43] [40]. This advanced fabrication technique allows researchers to build sophisticated models of human tissues and disease states that more accurately recapitulate the dynamic nature of native tissue environments, providing powerful platforms for studying disease mechanisms, screening drug efficacy and toxicity, and developing personalized regenerative therapies [44] [41].

The Convergence of 3D Bioprinting and Cellular Reprogramming

Fundamentals of the 3D Microenvironment in Cellular Reprogramming