Timing is Everything: Strategic Control of Reprogramming Factor Expression for Efficient Cell Fate Conversion

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role that the timing, dynamics, and stoichiometry of reprogramming factor expression play in directing cell fate. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational principles, current methodological applications, and optimization strategies. The scope ranges from mastering the core molecular mechanisms and leveraging computational tools for factor discovery, to implementing precise temporal control via chemical and genetic systems for enhanced efficiency and safety. It further explores the critical balance between rejuvenation and tumorigenicity in therapeutic contexts, supported by comparative validation of in vivo models and single-cell omics. This resource is designed to guide the rational development of robust and clinically viable reprogramming protocols.

Timing is Everything: Strategic Control of Reprogramming Factor Expression for Efficient Cell Fate Conversion

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role that the timing, dynamics, and stoichiometry of reprogramming factor expression play in directing cell fate. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational principles, current methodological applications, and optimization strategies. The scope ranges from mastering the core molecular mechanisms and leveraging computational tools for factor discovery, to implementing precise temporal control via chemical and genetic systems for enhanced efficiency and safety. It further explores the critical balance between rejuvenation and tumorigenicity in therapeutic contexts, supported by comparative validation of in vivo models and single-cell omics. This resource is designed to guide the rational development of robust and clinically viable reprogramming protocols.

The Core Clockwork: Unraveling the Fundamental Principles of Reprogramming Timing

The metaphor of Waddington's epigenetic landscape, conceived in the mid-20th century, describes cellular differentiation as a ball rolling downhill through branching valleys, each representing a distinct cellular fate [1] [2]. While this model beautifully illustrates the stability of differentiated states and the hierarchical nature of development, modern molecular biology has revealed a critical dimension missing from the original picture: time. Cellular reprogramming—the forced reversal of this downhill journey—is not a simple matter of pushing the ball back up the hill; it is a process governed by molecular switches and, fundamentally, constrained by timing.

Contemporary research has quantified this landscape through mathematical models of gene regulatory networks (GRNs). A common motif in these networks involves genes that self-activate and mutually inhibit one another, creating bistable switches that define distinct cell fates [1] [3]. The introduction of time-delayed feedback into these models, accounting for the finite time required for epigenetic rearrangement and multi-step molecular reactions, has been shown to create fundamental timing barriers. These delays can lead to long-lived oscillatory states where cells are trapped in a "limbo," neither in the initial nor the final state, and can even enable direct transdifferentiation (the conversion of one differentiated cell type to another without returning to a pluripotent state) [1]. This provides a theoretical basis for why the timing and duration of reprogramming factor expression are so critical.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Timing Barriers in Reprogramming

Q1: Why does the reprogramming process take several weeks and often result in low efficiency? Reprogramming is a multi-step progression that involves dismantling the somatic gene expression program and establishing a new pluripotency network. This is not a single event but a slow, stochastic process where cells must overcome multiple epigenetic barriers [4] [5]. The low efficiency stems from the fact that most cells fail to successfully navigate this sequence. The core reprogramming factors Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 (OSK) initiate the process, but the stable activation of the endogenous pluripotency network is a late event. The gradual nature of this process means that the duration of factor expression is a key determinant of success; too short, and the cell reverts to its original state [5].

Q2: What are the primary molecular barriers that slow down reprogramming? Several well-characterized molecular pathways act as roadblocks to reprogramming, effectively raising the "energy wall" a cell must overcome to change its identity [2]. The table below summarizes the key barriers and their mechanisms.

Table 1: Key Molecular Barriers to Efficient Reprogramming

| Barrier | Molecular Function | Impact on Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|

| p53/p21 Pathway [4] [6] | Tumor suppressor; cell cycle checkpoint and senescence pathway. | Acts as a major barrier by preventing the rapid cell division often required for reprogramming, thereby drastically reducing efficiency. |

| p16Ink4a/p19Arf [4] | Senescence pathway. | Similar to p53, its activation induces cellular senescence, halting the reprogramming process. |

| Native Somatic Gene Network [4] | Established transcriptional and epigenetic program of the starting cell. | This stable network is resistant to change and must be actively silenced for reprogramming to occur. |

| Chromatin Regulators (e.g., H3K9me3, MacroH2A) [4] [7] | Repressive chromatin modifications that enforce a closed chromatin state. | Create a physical barrier that prevents reprogramming factors from accessing their target DNA sequences. |

Q3: How does the "epigenetic barrier" in progenitor cells set the pace for neuronal maturation? Recent research in human neuronal maturation has revealed that the pace of development is set by a cell-intrinsic clock established well before neurogenesis. An epigenetic barrier composed of specific factors like EZH2, EHMT1/2, and DOT1L is put in place in neural progenitor cells. This barrier holds transcriptional maturation programs in a "poised" state. The gradual release of this barrier, not the initiation of the program, is what dictates the slow timeline of human neuronal maturation. Transient inhibition of these factors in progenitors leads to precocious maturation of subsequently born neurons, demonstrating that timing is an actively regulated property, not a passive process [8].

Troubleshooting Guides for Reprogramming Experiments

Problem: Low Reprogramming Efficiency

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Inadequate duration of reprogramming factor expression.

- Solution: The duration of the chemical drive (e.g., doxycycline induction) is critical. Experimental data shows a clear threshold is required. For example, in one study, providing input for less than ~7 days resulted in no reprogramming, while over ~14 days was needed to reach the pluripotent state [1]. Systematically optimize the timing of factor expression for your specific cell type.

- Protocol: Perform a time-course experiment. Induce factor expression with doxycycline for 7, 10, 14, and 21 days. Fix cells and stain for pluripotency markers (e.g., Nanog) to determine the minimal effective duration.

Cause 2: Dominance of senescence pathways and cell cycle arrest.

- Solution: Transiently inhibit key barrier pathways. Knockdown or pharmacological inhibition of p53 or p21 can dramatically enhance reprogramming efficiency by allowing the necessary cell divisions [4] [6].

- Protocol: Transfert somatic cells with siRNA against p53 or treat with a p53 inhibitor (e.g., Pifithrin-α) concurrently with the initiation of reprogramming factor expression. Note: Permanent suppression of these pathways should be avoided due to risks of genomic instability [6].

Cause 3: Inefficient Mesenchymal-to-Epithelial Transition (MET).

- Solution: The early phase of reprogramming requires MET. Enhance this process by inhibiting the TGF-β pathway (a pro-EMT signal) and/or activating BMP-Smad signaling (a pro-MET signal) [4] [5].

- Protocol: Add small molecule inhibitors of TGF-β signaling (e.g., SB431542) or BMP4 to the culture medium during the first week of reprogramming.

Problem: Incomplete Reprogramming and "Stuck" Intermediate States

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: The cells are trapped in a long-lived oscillatory or "Area 51" state.

- Solution: Mathematical models incorporating time-delayed feedback show that an interplay between the timing of the chemical drive and internal feedback loops can create stable intermediate states [1]. To push cells out of this state, consider enhancing the reprogramming network with late-acting factors.

- Protocol: Introduce late-stage enhancer factors like GLIS1 or Nanog alongside the core OSKM factors. GLIS1 has been shown to specifically promote the conversion of partially reprogrammed cells to a fully reprogrammed state without expanding the partially reprogrammed population [5].

Cause 2: Failure to activate the endogenous pluripotency network.

- Solution: The initial phases of reprogramming are driven by the ectopic factors. The final, stable step is the auto-activation of the endogenous pluripotency genes. This often fails. Using engineered, more potent factors can help.

- Protocol: Utilize engineered versions of reprogramming factors, such as Sox2 with a single amino acid replacement (Sox17EK) or factors fused to the VP16 transactivation domain, which have been shown to increase both the efficiency and kinetics of reprogramming [4].

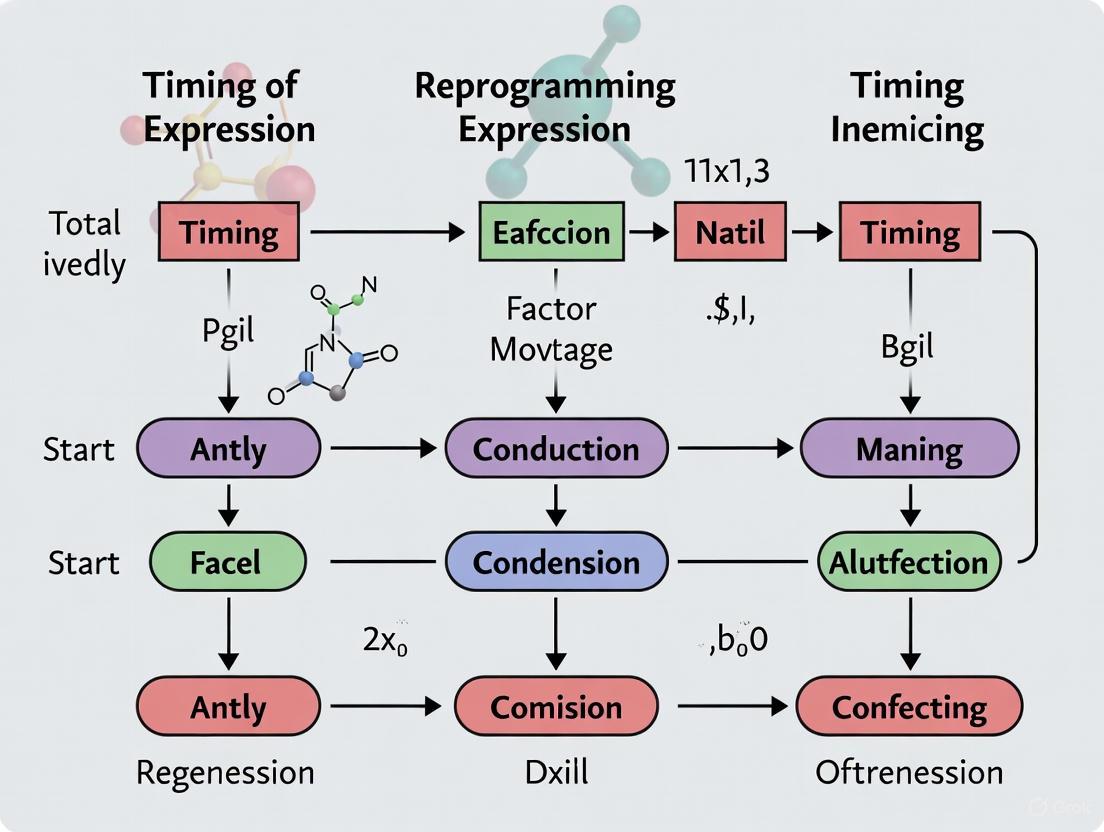

Visualizing the Timing Barrier

The following diagram illustrates the modern molecular understanding of Waddington's landscape, incorporating the timing barriers discussed.

Diagram 1: The Modern Waddington Landscape with Molecular Barriers. The journey from a differentiated state back to pluripotency is hindered by specific molecular barriers. Insufficient reprogramming drive can trap cells in an oscillatory state, while targeted interventions can sometimes enable a direct switch to another fate (transdifferentiation).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Overcoming Timing Barriers

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Modulating Reprogramming Timing and Efficiency

| Reagent / Factor | Type | Primary Function in Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|

| Core Factors (OSKM) [5] [6] | Transcription Factors | Initiate the reprogramming cascade; Oct4 and Sox2 are essential. |

| c-Myc [5] [6] | Transcription Factor/Oncogene | Enhances early reprogramming, promotes proliferation, and alters chromatin accessibility. |

| GLIS1 [4] [5] | Transcription Factor (Enhancer) | Acts at late stages to stabilize the pluripotent network and reduce partially reprogrammed cells. |

| p53/p21 siRNA or Inhibitors [4] [6] | Barrier Inhibition | Transiently suppresses senescence and cell cycle checkpoints to enhance efficiency. |

| TGF-β Inhibitor (e.g., SB431542) [4] [5] | Small Molecule | Promotes Mesenchymal-to-Epithelial Transition (MET), a critical early step. |

| BIX-01294 [6] | Small Molecule (Epigenetic) | Inhibits histone methyltransferase G9a, an epigenetic barrier, can replace Oct4 in some contexts. |

| Vitamin C [4] | Small Molecule (Epigenetic) | Acts as a cofactor for demethylases, promoting a more open chromatin state and improving efficiency. |

The discovery that somatic cells can be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) through the ectopic expression of OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (collectively known as OSKM) has revolutionized regenerative medicine and developmental biology [9]. While the necessity of these factors is well-established, emerging research underscores that their temporal expression sequence is equally critical for efficient reprogramming. The conventional approach of simultaneous OSKM delivery often results in low efficiency and slow kinetics, with only a rare fraction of cells successfully reaching pluripotency [10] [11]. This technical guide addresses the molecular underpinnings of the OSKM transcriptional cascade and provides evidence-based troubleshooting solutions to optimize reprogramming protocols by leveraging temporal control of factor expression.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Why does the sequence of reprogramming factor addition matter?

Answer: The sequential addition of OSKM factors aligns with the natural progression of molecular events required for cell fate conversion. Research demonstrates that adding factors in a specific sequence (OCT4 and KLF4 first, followed by c-MYC, and finally SOX2) can improve reprogramming efficiency by approximately 300% compared to simultaneous addition [11].

This specific sequence favors a critical biological transition: it drives fibroblasts through a state with enhanced mesenchymal characteristics before initiating the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) essential for pluripotency. Adding OCT4 first induces a hyper-mesenchymal state by upregulating genes like Slug (Snail2), which may create a more homogeneous and receptive cell population. Crucially, delayed SOX2 introduction prevents premature MET, as SOX2 has been shown to suppress Slug expression and promote epithelialization. This temporal separation allows necessary epigenetic remodeling to occur before the final push toward pluripotency [11].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Low Reprogramming Efficiency

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Consistently low iPSC yield | Non-optimized, simultaneous factor addition | Implement sequential protocol: OK (Days 1-3) → +M (Days 4-6) → +S (Day 7 onward) [11] |

| Incomplete metabolic reprogramming | Failure to transition through necessary intermediate states | Pre-condition cells in hypoxia-mimicking conditions; validate upregulation of early mesenchymal markers [12] |

| High cell death during early stages | Overwhelming innate immune response to viral transduction | Switch to non-viral delivery methods (e.g., nucleofection, episomal plasmids) or include anti-inflammatory agents [12] [13] |

What are the initial molecular events triggered by OSKM induction?

Answer: The earliest cellular response to OSKM, particularly when delivered via viral vectors, is a potent innate immune response and cellular stress, characterized by the expression of genes involved in "response to virus" and "immune response" pathways [12]. This is quickly followed by oxidative stress, DNA damage response, activation of p53, and induction of senescence or apoptosis, which collectively create a major roadblock for the majority of cells [12].

Despite this stress, legitimate reprogramming initiates within the first 24-72 hours. Key events include the gradual suppression of fibroblast-enriched transcription factors (the "downreprogramome") and the activation of pluripotency-associated surface markers like CD24, PDPN, and PODXL [10] [12]. Approximately 83 transcription factors that are initially responsive to OSKM undergo this legitimate reprogramming, biasing the process toward a successful outcome despite its overall inefficiency [10].

Summary of Key Early Molecular Responses to OSKM (0-72 hours)

| Time Post-Induction | Upregulated Processes/Genes | Downregulated Processes/Genes |

|---|---|---|

| 24-48 hours | Innate immune response, ROS generation, DNA damage response [12] | Fibroblast-specific surface markers [12] |

| 48-72 hours | Pluripotency-associated surface antigens (CD24, PODXL) [12]; Mesenchymal genes (e.g., Slug) with sequential OK-first protocol [11] | Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) genes (with concurrent OSKM) [12] |

| 72 hours onward | Metabolic pathway genes (shift toward glycolysis) [9] | Somatic program "erasome" TFs, including HOX genes [10] |

How can I enhance reprogramming efficiency and kinetics?

Answer: Beyond sequential factor addition, efficiency can be significantly enhanced by targeting the chromatin state of the somatic genome and mitigating initial stress responses.

Chromatin Relaxation: The OSKM factors, particularly OCT4, act as "pioneer factors" that can bind to closed chromatin and initiate its opening [14]. This process can be augmented with small molecules:

Stress Mitigation: Using non-integrating delivery methods (e.g., mRNA, episomal plasmids, or proteins) can avoid the intense innate immune response triggered by viral vectors [12] [13]. Transiently suppressing the p53 pathway or using antioxidants can also reduce the burden of DNA damage response and senescence [12] [14].

How do I avoid teratoma formation in applied reprogramming?

Answer: The key to avoiding teratoma formation is transient expression of the reprogramming factors. Sustained expression of OSKM in vivo leads to uncontrolled proliferation and teratomas [13] [15]. Strategies for control include:

- Inducible Systems: Using doxycycline-inducible promoters that allow for precise control over the duration of OSKM expression. Short pulses (e.g., 2 days on/5 days off) have been shown to rejuvenate tissues and enhance regeneration without causing teratomas [13] [15].

- Non-Integrating Delivery: Utilizing delivery vectors that do not integrate into the host genome, such as episomal plasmids or Sendai virus, ensures the factors are diluted and silenced over time [13].

- Factor Modification: Omitting the potent oncogene c-MYC from the cocktail can reduce tumorigenic potential while still allowing for successful reprogramming, though with lower efficiency [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Reagents for Investigating OSKM Timing

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Utility | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline-Inducible Systems | Enables precise temporal control of OSKM expression in transgenic models [11] [13]. | Ideal for in vivo studies and testing sequential regimens; requires generation of stable lines. |

| Non-Integrating Episomal Plasmids | Delivers OSKM without genomic integration, ensuring transient expression [13]. | Critical for clinical translation; reduces risk of insertional mutagenesis and teratomas. |

| Small Molecule Enhancers (VPA, CHIR99021, Vitamin C) | Modulates chromatin state and signaling pathways to enhance reprogramming legitimacy [14]. | Can replace specific factors (e.g., VPA for c-MYC); improves efficiency and kinetics. |

| AAV9 Delivery Vectors | Provides high-transduction efficiency for in vivo reprogramming studies [15]. | Offers broad tissue tropism; useful for systemic delivery in animal models. |

| Pluripotency Surface Marker Antibodies (e.g., anti-CD24, anti-PODXL) | FACS-based isolation of cells successfully initiating reprogramming [12]. | Allows pre-selection of responsive cells at early stages (72h), enriching the final iPSC yield. |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Visualization

Sequential OSKM Reprogramming Workflow

The following diagram outlines a optimized experimental protocol for sequential factor addition, integrating key troubleshooting steps:

Molecular Pathway of Sequential Reprogramming

This diagram illustrates the core molecular logic behind the sequential OSKM protocol and its contrast with simultaneous addition:

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Reprogramming Challenges

Problem 1: Low Reprogramming Efficiency

- Question: "I am using the correct transcription factors, but my reprogramming efficiency remains very low. What could be the issue?"

- Investigation & Solution:

- Check Expression Levels: Constitutively high expression of reprogramming factors can be problematic and even induce cell death [16]. The protein levels of key factors like Ngn2 are dynamically regulated in vivo via rapid degradation (e.g., a 30-minute half-life) [16]. Ensure your expression system does not lead to supraphysiological levels that are toxic to cells.

- Review Factor Stoichiometry: The balance of factors is critical. In fibroblast reprogramming, a 1:1:1:1 ratio of OSKM from a polycistronic vector is standard, but it still results in low efficiency because it does not account for temporal needs [17] [11]. Consider titrating individual factor levels or using sequential addition protocols.

Problem 2: Incomplete Reprogramming and Somatic Memory

- Question: "My induced cells express pluripotency markers but also retain signatures of the original somatic cell. How can I achieve more complete reprogramming?"

- Investigation & Solution:

- Focus on Enhancer Inactivation: Incomplete silencing of the somatic program is a major barrier. Reprogramming factors like OSK work in part by redistancing broadly expressed somatic TFs (like AP-1, CEBP, and ETS) away from somatic enhancers and toward new pluripotency enhancers [18]. Evaluate the closure of somatic enhancers using markers like loss of H3K27ac.

- Ensure Endogenous Network Activation: The ultimate goal is to activate the endogenous pluripotency network so that the cells become independent of transgenes [17] [19]. The late stage of reprogramming is marked by the activation of endogenous Oct4 and Nanog [17] [18]. Use reporter cell lines to monitor the activation of these endogenous genes.

Problem 3: Generation of Off-Target Cell Types

- Question: "When aiming for iPSCs, I am observing the emergence of trophectoderm- or neural-like cells. Why does this happen?"

- Investigation & Solution:

- Recognize Inherent Plasticity: The OSKM reprogramming cocktail can produce a spectrum of cell states, including trophectoderm and extraembryonic endoderm, not just iPSCs [18] [20]. This indicates a high degree of plasticity during the process.

- Optimize the "Transcription Factor Code": The specific combination and levels of factors determine the outcome. For example, during development, the balance between Ngn2/NeuroD1 and Ascl1 dictates the generation of glutamatergic versus GABAergic neurons [16]. Fine-tuning the ratio of your reprogramming factors can help guide cells toward the desired lineage.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is the timing of reprogramming factor expression so important? Simultaneous expression of all factors may not reflect the natural process of development, where factors are expressed in a sequential, wave-like manner [16]. Forcing a cell to execute all steps at once is inefficient. A seminal study demonstrated that sequentially adding factors—first Oct4 and Klf4, then c-Myc, and finally Sox2—can improve reprogramming efficiency by 300% compared to simultaneous addition [11]. This sequence allows the cells to pass through a hyper-mesenchymal state before undergoing a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), which appears to be a more effective path [11].

FAQ 2: Can I reprogram cells without overexpressing Oct4? Yes, under certain conditions. While exogenous Oct4 is sufficient and was a foundational part of the original protocol, it is not always strictly necessary [19]. Endogenous Oct4 expression is the critical requirement. Reprogramming can be achieved with other combinations of factors (e.g., Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc plus alternative factors like Sall4, Nanog, Esrrb, and Lin28) that can activate the endogenous Oct4 locus [21] [19]. Notably, generating iPSCs without exogenous Oct4 may produce higher-quality pluripotent stem cells with superior developmental potential [19].

FAQ 3: What are the major epigenetic barriers to reprogramming, and how can they be overcome? The two primary epigenetic barriers are:

- Silencing of the Somatic Program: The starting cell's identity is maintained by a robust enhancer network. OSKM indirectly inactivate these somatic enhancers by recruiting "broadly expressed" somatic TFs (AP-1, CEBP, ETS) away from them, leading to a loss of active chromatin marks [18].

- Activation of the Pluripotency Program: The reprogramming factors must subsequently bind to and open chromatin at pluripotency-specific enhancers to establish the new cell identity [17] [18]. These barriers can be lowered using small molecules. For instance, Vitamin C is known to improve reprogramming efficiency [11], and inhibition of proteins like MLL1 or perturbation of SUMO pathways can destabilize the somatic enhancer landscape and promote reprogramming [18].

Table 1: Impact of Sequential vs. Simultaneous Factor Addition on Reprogramming

| Factor Delivery Method | Protocol Summary | Key Cellular Process | Reported Outcome | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential Addition | Add Oct4 + Klf4, then c-Myc, then Sox2 with a delay. | Induces a hyper-mesenchymal state before MET. | ~300% increase in reprogramming efficiency in both mouse and human cells. | [11] |

| Simultaneous Addition | All factors (OSKM) introduced at the same time. | MET occurs without an intermediate hyper-mesenchymal state. | Standard, low-efficiency protocol (Baseline ~0.1% in mouse). | [11] |

Table 2: Key Reprogramming Factor Functions and Expression Dynamics

| Reprogramming Factor | Core Function in Development | Expression Dynamics & Protein Stability | Consideration for Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| NeuroD1 | Drives differentiation of post-mitotic neurons [16]. | Expression is transient; downstream effectors (NeuroD2/4) take over [16]. | Constitutive high expression may be non-physiological and block maturation. |

| Ngn2 | Promotes cell cycle exit of neural progenitors [16]. | Protein has a short half-life (~30 min); expression oscillates in development [16]. | Rapid degradation needs to be accounted for; sustained high levels may be detrimental. |

| Oct4 | Master regulator of pluripotency [19]. | Tightly controlled levels are critical; slight deviations trigger differentiation [19]. | Precise control of expression level is mandatory for high-quality iPSCs. |

| Ascl1 | Instructs neurogenesis of GABAergic interneurons [16]. | Competes with Ngn2/NeuroD1; balance determines neuronal subtype [16]. | The relative level to other factors can determine the resulting cell subtype. |

Key Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Reprogramming Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Reprogramming | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Inducible Expression Systems | Allows precise temporal control over factor expression (e.g., Tet-On/Off) [17]. | Critical for testing sequential addition protocols and for withdrawing factors once the endogenous network is active. |

| Polycistronic Vectors | Delivers multiple reprogramming factors in a fixed stoichiometry from a single transcript [17]. | Ensures that every transfected cell receives all factors, reducing heterogeneity. Useful for establishing baseline efficiency. |

| Small Molecules (e.g., Vitamin C) | Modulates epigenetic barriers to improve efficiency [11]. | Can replace certain transcription factors or enhance the quality of the resulting iPSCs. |

| Cell Lineage Tracing Systems | Unambiguously tracks the origin of reprogrammed cells [16]. | Essential for validating that resulting neurons or iPSCs are derived from the intended target somatic cell and not from contaminating cells. |

| Synthetic Reprogramming Factors | Fusion proteins (e.g., OCT4-VP16) with enhanced transcriptional activity [21]. | Can significantly increase reprogramming speed and efficiency, but may alter the natural dynamics of the process. |

Within the broader thesis on the timing of reprogramming factor expression, a critical challenge emerges: the process of epigenetic reprogramming is a race against tightly regulated cellular clocks. Successful reprogramming of somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) requires precise temporal control over factor expression to navigate the delicate balance between epigenetic rejuvenation and complete dedifferentiation. Research reveals that ectopic expression of transcription factors initiates a complex, timed sequence of chromatin remodeling events that must occur in proper sequence to reset cellular identity without triggering tumorigenesis or cell death. This technical support center addresses the specific experimental challenges researchers face when investigating and controlling these dynamic processes, providing troubleshooting guidance for common issues encountered in timing-focused reprogramming research.

Key Experimental Findings: Quantitative Dynamics of Early Reprogramming

Table 1: Early Chromatin Modification Dynamics During Reprogramming

| Time Point | H3K4me2 Changes | H3K27me3 Changes | Transcriptional Activation | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-division (0 divisions) | Significant increase at >1,500 loci | Focused depletion at H3K4me2-gain positions | Not yet observed | Earliest epigenetic response, precedes transcription |

| Early divisions (1-2 divisions) | Continuously increasing | Patterns largely unchanged except localized depletion | Limited to pre-accessible chromatin | Priming of pluripotency gene promoters |

| Later stages (>3 divisions) | Established at pluripotency targets | Reconfiguration continues | Activation of primed genes | Establishment of stable pluripotent state |

Studies demonstrate that histone modification H3K4me2 exhibits dramatic changes at over 1,500 gene loci during early reprogramming, continuously increasing with successive cell divisions [22]. These changes are strikingly decoupled from transcriptional activation, occurring even in populations that have not yet divided based on CFSE intensity measurements [22]. This chromatin remodeling preferentially targets essential pluripotency and developmentally regulated genes like Sall4, Lin28, and Fgf4, which do not become transcriptionally active until later stages of iPS cell formation [22].

Table 2: Chromatin Accessibility Dynamics in Naïve vs. Primed Reprogramming

| Reprogramming Phase | ATAC-Seq Peak Dynamics | Transcriptome Divergence | Key Regulatory Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 6 (medium change) | Significant juncture in accessibility | Minimal divergence | Environmental response factors |

| Day 8 | Begins to differ between naïve/primed | Dramatic shift in primed reprogramming | PRDM1 isoforms, early TFs |

| Day 14 | Established patterns | Dramatic shift in naïve reprogramming | Pluripotency network factors |

| Days 20-24 | Stable chromatin state | Minimal divergence from iPSCs | Maintenance factors |

Research comparing naïve and primed reprogramming trajectories reveals that chromatin accessibility changes precede transcriptional changes, with accessibility beginning to differ on day 8, while dramatic transcriptome discrepancies emerge around day 14 [23]. The number of open-to-closed (OC) regions consistently outnumbers closed-to-open (CO) regions until day 20 during naïve reprogramming, indicating extensive shutdown of the somatic program precedes full activation of pluripotency networks [23].

Essential Methodologies for Timing Research

CFSE Labeling for Division-Coupled Analysis

Protocol Objective: To isolate and analyze cells that have undergone defined numbers of divisions during reprogramming, enabling precise correlation of epigenetic changes with cell division history [22].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Utilize inducible secondary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) with doxycycline-controlled OSKM expression

- Combine carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) live staining with serum pulsing protocol

- Isolate doxycycline-induced cells based on CFSE fluorescence intensity reduction corresponding to 0, 1, 2, or >3 divisions

- Confirm fluorescence intensity remains unchanged in serum-starved controls without division

- Validate that CFSE labeling does not interfere with reprogramming capacity through global transcriptional analysis

- Collect all cells in arrested (serum-starved) state except final continuously dividing sample

Troubleshooting Notes: Ensure consistent serum starvation conditions across replicates. Validate division counting with control populations. Confirm CFSE does not affect cell viability beyond 96 hours.

ATAC-Seq for Chromatin Accessibility Mapping

Protocol Objective: To profile genome-wide chromatin accessibility dynamics throughout reprogramming trajectories [23].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Employ secondary human reprogramming system with inducible Yamanaka factors

- Harvest CD326+ pluripotent intermediates at days 6, 8, 14, 20, and 24 alongside initial fibroblasts and final iPSCs

- Prepare nuclei for transposase-based tagmentation

- Sequence accessible chromatin regions

- Identify permanently open (PO), closed-to-open (CO), and open-to-closed (OC) regions

- Correlate accessibility changes with RNA-seq data from same time points

- Compare naïve versus primed reprogramming trajectories

Troubleshooting Notes: Maintain consistent cell numbers for tagmentation reactions. Include biological replicates for each time point. Normalize for potential batch effects across time series.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Addressing Common Timing Challenges in Reprogramming

Q: Our reprogramming efficiency remains low despite optimizing factor expression. What timing-related issues should we investigate?

A: Low efficiency often stems from improper temporal control. Focus on these aspects:

- Epigenetic barrier timing: Analyze H3K4me2 patterns early in reprogramming (before 3 divisions) - absence of changes at pluripotency loci indicates failed priming [22]

- Cell division coupling: Use CFSE labeling to verify changes are division-coupled as expected [22]

- Ancestry-dependent effects: Consider genetic background influences on optimal timing, as reprogramming efficiency-associated genes show ancestry-dependent expression patterns [24]

Q: How can we determine whether our reprogramming system is following naïve versus primed trajectories based on timing?

A: Monitor these temporal markers:

- Chromatin accessibility divergence: Naïve and primed paths show distinct ATAC-seq patterns by day 8 [23]

- Transcriptional activation timing: Primed reprogramming shows dramatic transcriptome shifts by day 8, while naïve shifts occur around day 14 [23]

- PRDM1 isoform expression: PRDM1α and PRDM1β show distinct temporal expression and targeting during naïve reprogramming [23]

Q: What are the critical time points for assessing successful epigenetic reprogramming initiation?

A: These timepoints are particularly revealing:

- Pre-division phase: Check for early H3K4me2 changes at pluripotency promoters before first division [22]

- Day 6-8 window: Assess chromatin accessibility shifts following medium change [23]

- Division 3+: Evaluate establishment of stable H3K4me2 patterns and focused H3K27me3 depletion [22]

Troubleshooting Experimental Challenges

Problem: High Heterogeneity in Reprogramming Populations

Symptoms: Mixed populations with varying epigenetic states, inconsistent differentiation potential.

Solutions:

- Implement CFSE labeling to division-enrich populations and reduce heterogeneity [22]

- Use surface markers (CD326) to isolate pluripotent intermediates at specific time points [23]

- Apply single-cell ATAC-seq to profile chromatin heterogeneity across populations

- Utilize reporter systems for real-time tracking of reprogramming progression

Problem: Incomplete Silencing of Somatic Program

Symptoms: Persistent expression of somatic genes, failure to fully activate pluripotency network.

Solutions:

- Extend reprogramming factor expression while monitoring for OC region formation [23]

- Verify H3K27me3 depletion at sites of H3K4me2 gain [22]

- Check that open-to-closed (OC) regions outnumber closed-to-open (CO) regions in early phases [23]

- Analyze somatic gene enhancer transitions, which represent higher-order cell state transition [22]

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Dynamics

Early Epigenetic Response to Reprogramming Factors

Naïve versus Primed Reprogramming Trajectories

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Timing-Focused Reprogramming Research

| Reagent/Cell System | Specific Function | Application in Timing Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Inducible Secondary MEFs | Doxycycline-controlled OSKM expression | Enables synchronous, homogeneous factor induction across population [22] |

| CFSE Cell Tracking Dye | Division counting via fluorescence dilution | Correlates epigenetic changes with precise division history [22] |

| ATAC-Seq Reagents | Chromatin accessibility mapping | Profiles open/closed chromatin dynamics across time course [23] |

| H3K4me2/H3K27me3 Antibodies | Histone modification mapping by ChIP-seq | Tracks activating/repressive chromatin state transitions [22] |

| PRDM1α/PRDM1β Isoform-Specific Tools | Distinct roles in naïve reprogramming | Dissects isoform-specific temporal functions [23] |

| CD326 (EpCAM) Microbeads | Pluripotent intermediate isolation | Enriches reprogramming populations at specific stages [23] |

| Naïve (5iLAF) vs Primed Media | Captures distinct pluripotency states | Controls reprogramming trajectory for timing comparisons [23] |

The race against the cellular clock in epigenetic remodeling demands precise temporal control of reprogramming factor expression. Successful navigation of this process requires researchers to monitor early chromatin priming events, understand the distinct trajectories of naïve versus primed reprogramming, and account for genetic background influences on timing. The methodologies and troubleshooting guides presented here provide a framework for addressing the most common challenges in timing-focused reprogramming research. By applying these tools and understanding the quantitative dynamics of epigenetic remodeling, researchers can advance toward more efficient and controlled cellular reprogramming for both basic research and therapeutic applications.

The following table defines the core cellular reprogramming processes, their key features, and markers to distinguish them in experimental settings.

| Process | Definition & Trajectory | Key Features & Markers | Final Cell State/Potency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dedifferentiation [25] [26] | Reversion to a less specialized, earlier state within the same cell lineage. | • Downregulation of terminal differentiation markers (e.g., Myogenin in myotubes [25], myelin-associated genes in Schwann cells [26])• Re-entry into the cell cycle• Upregulation of progenitor/immature markers (e.g., MSX1, p75NTR) [25] [26] | Multipotent or unipotent progenitor within the original lineage [25]. |

| Transdifferentiation [25] [27] | Direct conversion from one differentiated cell type to another, bypassing a pluripotent intermediate. | • Loss of original somatic identity markers• Acquisition of new lineage-specific markers• Often involves a brief, partially reprogrammed state | Differentiated cell of a new lineage [27]. |

| Rejuvenation [28] [29] | Reversal of aged phenotype without a change in cell identity. Epigenetic "reset" of aging hallmarks. | • Reversal of epigenetic aging clocks• Retention of somatic cell identity and function• Absence of pluripotency marker expression | The original, specialized cell type, but with a younger molecular profile [28]. |

Experimental Protocols for Fate Conversion

Protocol 1: Inducing Dedifferentiation in Vitro

This protocol is adapted from studies on dedifferentiating degenerative human nucleus pulposus cells (dNPCs) into induced notochordal-like cells (iNCs) [30].

- 1. Cell Source Preparation: Obtain terminally differentiated somatic cells. For a pure population, use Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to isolate target cells (e.g., for dNPCs, sort for CD90−TIE2− cells to eliminate progenitor contamination) [30].

- 2. Reprogramming Factor Delivery:

- Identified Factor Combination: OCT4, FOXA2, TBXT (OFT) [30].

- Delivery System: Use lentiviral vectors for stable gene expression. Optimize the Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) for high efficiency without excessive cytotoxicity.

- 3. Culture Conditions: Maintain transfected cells in a specialized medium that supports the progenitor state. For iNCs, use notochordal precursor-conditioned medium to maintain the dedifferentiated phenotype [30].

- 4. Timeline & Monitoring: The process can take 1-3 weeks. Monitor daily for morphological changes (e.g., shift from fibroblastic to a more rounded, vacuolated morphology). Assess the downregulation of differentiation markers (e.g., COL1A1) and upregulation of progenitor markers (e.g., KRT8, NOTO) via qPCR or immunostaining at days 7, 14, and 21 [30].

Protocol 2: Achieving Rejuvenation via Partial Reprogramming

This protocol outlines the use of the Yamanaka factors for a transient, non-pluripotent rejuvenation effect [28] [29].

- 1. Factor Selection: Use the OSKM (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) factors. For enhanced safety, consider omitting c-MYC or using L-MYC as an alternative [31].

- 2. Transient Delivery System: Employ non-integrating delivery systems to avoid permanent genetic alteration and prevent full pluripotency induction. Options include:

- 3. Timing is Critical: The key parameter is the duration of factor expression. Short, cyclic induction (e.g., 1-3 days on, 4-5 days off) is sufficient to rejuvenate the epigenome without erasing cellular identity [29].

- 4. Validation of Rejuvenation:

- Primary Assay: Use DNA methylation clocks (e.g., Horvath's clock) on treated cells to quantify epigenetic age reduction [28].

- Secondary Assays: Confirm retention of original cell function and the absence of pluripotency markers (e.g., NANOG, SSEA-4) via RT-PCR, immunostaining, or functional assays [28].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My cells are not re-entering the cell cycle during a dedifferentiation attempt. What could be wrong? A: This is a common barrier, especially in aged or degenerative cells. Check the following:

- Reprogramming Factors: Ensure your factor combination includes a potent "epigenetic reset" factor like OCT4, which can remodel restrictive chromatin in degenerative cells [30].

- Cell Health: Degenerative cells have accumulated damage. Confirm your starting population is viable and consider using early-passage cells.

- Pathway Activation: Verify the activation of key signaling pathways like Wnt/β-catenin or BMP, which are necessary for cell cycle re-entry in many dedifferentiation contexts [25].

Q2: How can I be sure my cells are transdifferentiating and not just undergoing dedifferentiation followed by differentiation? A: To confirm direct lineage conversion, you must rigorously rule out a pluripotent intermediate.

- Lineage Tracing: Use a genetic lineage tracing system that marks the original cell population. The absence of unmarked, pluripotent colonies is a strong indicator of direct conversion [27].

- Temporal Analysis: Perform high-resolution time-course transcriptomic analysis (e.g., single-cell RNA-seq). This allows you to observe the direct molecular trajectory from cell type A to B, without detecting a distinct, off-target pluripotent cell cluster [27].

Q3: In partial reprogramming, how do I titrate factor expression to avoid teratoma formation? A: The risk of teratomas is linked to complete erasure of epigenetic identity.

- Use Non-Integrating Vectors: This is the most critical step, as it ensures factor expression is transient and self-limiting [31] [27].

- Short Induction Cycles: Do not induce factor expression continuously. Use pulse-like cycles (e.g., 2 days on/5 days off) and monitor pluripotency markers after each cycle. Stop immediately if they are detected [29].

- Novel Factors: Emerging research identifies single-gene interventions (e.g., "SB000") that can achieve rejuvenation without activating the core pluripotency network, thereby eliminating the teratoma risk [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents for designing and analyzing reprogramming experiments.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Core Transcription Factors | Master regulators that drive cell fate conversion. | • OSKM: Gold standard for pluripotency/rejuvenation [31] [29].• OFT (OCT4, FOXA2, TBXT): For dedifferentiation to notochordal lineage [30].• BAM (Ascl1, Brn2, Myt1l): For transdifferentiation into neurons [27]. |

| Non-Integrating Delivery Systems | Enables transient, safer factor expression. | • Sendai Virus: High efficiency, non-integrating RNA virus [31].• Synthetic mRNA: Requires repeated transfection but is highly controllable [27].• Episomal Plasmids: DNA-based, but can be diluted out over cell divisions [31]. |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | Improve efficiency, replace transcription factors, or modulate key pathways. | • VPA (Valproic Acid): Histone deacetylase inhibitor [31].• CHIR99021: GSK-3 inhibitor that activates Wnt/β-catenin pathway [27].• RepSox: TGF-β inhibitor that can replace SOX2 [31]. |

| Key Pathway Modulators | To activate or inhibit signaling pathways critical for reprogramming. | • BMP Signaling: Necessary for dedifferentiation in tadpole and mouse models [25].• Wnt/β-catenin: Activation induces dedifferentiation in epithelial cells [25].• Notch Signaling: Regulates dedifferentiation in Schwann cells and tadpole tails [25] [26]. |

| Analysis & Validation Tools | To characterize the identity and state of the resulting cells. | • DNA Methylation Clocks: The gold standard for quantifying epigenetic rejuvenation [28].• Single-Cell RNA-Seq: Unravels heterogeneity and maps the precise trajectory of conversion [30].• Lineage Tracing Systems: Genetically confirms the origin of converted cells and rules out intermediates [27]. |

Visualizing the Pathways and Workflows

Cellular Reprogramming Trajectories

Key Signaling Pathways in Dedifferentiation

Precision Timing in Practice: Methodologies for Controlled Factor Delivery and Expression

The precise timing of gene expression is a cornerstone of biological research, especially in studies of cellular reprogramming. Controlling when and how reprogramming factors are expressed can be the difference between successful lineage conversion and uncontrolled cell division or apoptosis. While retroviral vectors were among the first tools enabling gene delivery, their permanent integration and sustained expression present significant limitations for temporal control. This technical resource outlines advanced toolkits that enable researchers to move beyond constitutive expression systems toward precisely regulated temporal control of gene expression.

Modern approaches for temporal control primarily center on three strategic pillars: doxycycline-inducible systems for tunable transcription, mRNA transfection for immediate but transient protein expression, and small molecule-regulated protein stability. Each system offers distinct advantages and challenges in the context of reprogramming research, where the timing, duration, and level of factor expression critically influence experimental outcomes. The following sections provide detailed troubleshooting guidance, quantitative comparisons, and practical protocols to help researchers implement these systems effectively in their investigations of reprogramming dynamics.

Technical Support Center: Doxycycline-Inducible Systems

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What causes high background expression in my Tet-On system, and how can I minimize it? A: High background activity in the absence of doxycycline often stems from non-specific activation of the TRE promoter or suboptimal rtTA variants. To address this:

- Utilize advanced rtTA variants such as Tet-On 3G or V16, which contain specific mutations (F67S, R171K, F86Y, A209T) that dramatically reduce background activity while increasing doxycycline sensitivity [32].

- Ensure proper vector design by placing the TRE promoter in a lentiviral backbone with attenuated LTRs to minimize enhancer effects that can increase leakiness [33].

- Incorporate insulator elements around the TRE promoter to shield it from chromosomal position effects that may cause variable background expression.

Q: Why is my inducible system not responding to doxycycline treatment? A: Poor induction response can result from several factors:

- Verify doxycycline concentration and activity; effective concentrations typically range from 1-3 μg/mL, but optimization may be required for specific cell types [33].

- Check rtTA expression levels; weak promoters may insufficiently express the transactivator. Consider using stronger or different promoters, but be aware that the CMV promoter may be susceptible to silencing in some rodent cells [33].

- Validate system components sequentially: confirm rtTA expression first, then TRE-driven reporter expression before implementing your gene of interest.

Q: How can I achieve more uniform induction across my cell population? A: Heterogeneous response often stems from mixed populations with variable rtTA expression:

- Implement stringent antibiotic selection to eliminate non-expressing cells when using systems with linked resistance markers [33].

- For primary cells or difficult-to-transfect cells, consider simultaneous infection with both rtTA and response vector, which has demonstrated >95% inducibility in some systems [33].

- Utilize fluorescent reporters linked to your gene of interest via IRES or 2A peptides to identify and sort responsive populations.

Q: What strategies exist for tissue-specific inducible expression? A: Combining tissue-specific promoters with inducible systems enables spatial control:

- Replace constitutive promoters driving rtTA expression with tissue-specific promoters in lentiviral or RMCE systems [32].

- Implement recombination-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) systems for targeted integration into specific genomic loci like Collagen 1a1, ensuring consistent expression patterns [32].

- For animal models, consider cross-breeding tissue-specific Cre drivers with rtTA lines for sophisticated control schemes.

Troubleshooting Guide

Table: Common Problems and Solutions for Doxycycline-Inducible Systems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| High background expression | Non-specific TRE promoter activity | Use advanced Tet-On variants (3G/V16) [32] | Employ lentiviral vectors with attenuated LTRs [33] |

| Low induction fold-change | Weak rtTA expression or poor doxycycline permeability | Optimize doxycycline concentration (1-10 μg/mL range) | Use promoters resistant to silencing (e.g., PGK, EF1α) [33] |

| Inconsistent response across population | Heterogeneous rtTA expression | Implement dual antibiotic selection | Include fluorescent reporter for FACS sorting |

| Gradual loss of inducibility | Promoter silencing or genetic instability | Include chromatin insulators or use anti-silencing elements | Perform regular re-selection with antibiotics |

| Cellular toxicity | Doxycycline side effects or transgene overexpression | Titrate doxycycline to minimum effective concentration | Consider self-inactivating (SIN) vector designs |

Quantitative Performance Data

Table: Comparison of Tet-System Components and Their Performance Characteristics [33] [32]

| System Component | Options | Performance Characteristics | Recommended Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| rtTA Variants | Tet-On Advanced | 100-200 fold induction | Standard applications |

| Tet-On 3G | >200 fold induction, lower background | Sensitive primary cells | |

| V16 (F67S, R171K, F86Y, A209T) | Maximum sensitivity to doxycycline | Low doxycycline conditions | |

| Response Promoters | TREtight | Minimal background | Difficult-to-express genes |

| TRE3G | Optimized for Tet-On 3G | Most applications with Tet-On 3G | |

| Delivery Methods | Sequential transduction | >95% inducible cells | Primary cells with extended lifespan |

| Simultaneous transduction | >95% inducible cells | Rapid establishment | |

| RMCE | Consistent expression level | ES cells and precise genomic location |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Doxycycline-Inducible Systems [33] [32]

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transactivators | Tet-On Advanced, Tet-On 3G, V16 mutant | Binds TRE in presence of doxycycline | Select based on sensitivity requirements |

| Response Vectors | TREtight, TRE3G-luciferase, pLVTPT series | Regulates expression of gene of interest | TREtight offers lowest background |

| Selection Markers | Puromycin, Blasticidin, GFP/BFP | Enriches for successfully transduced cells | IRES-linked markers maintain expression |

| Delivery Vectors | Lentiviral, Retroviral, RMCE-compatible | Introduces system into target cells | Lentiviral for primary/non-dividing cells |

| Inducers | Doxycycline hydate, Doxycycline HCl | Activates rtTA binding to TRE | Hydate form for aqueous solutions |

Advanced Methodologies: Experimental Protocols

Establishing a Doxycycline-Inducible System in Primary Cells

This protocol outlines the simultaneous infection method for primary rat pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (PMVECs), achieving >95% inducibility [33].

Materials:

- Retroviral vector #2641 (LTR-rtTA-IRES-EGFP-Bsr) [33]

- Lentiviral reporter vector #2706 (TRE-Gluc-SV40-Puro) [33]

- Target primary cells (e.g., PMVECs)

- Phoenix ampho and HEK293FT packaging cells

- Polybrene (8 μg/mL working concentration)

- Blasticidin (30 μg/mL) and Puromycin (4 μg/mL) for selection

- Doxycycline (1-3 μg/mL for induction)

Procedure:

- Virus Production:

- Produce retroviral supernatants using CaPO4-mediated transfection of Phoenix ampho cells.

- Produce lentiviral supernatants using HEK293FT cells with psPAX2 and pMD2.G helper plasmids.

- Collect supernatants 48-72 hours post-transfection, filter through 0.45μm membrane.

Simultaneous Infection:

- Plate target cells at 20% confluence in 35-mm dishes.

- Mix retroviral and lentiviral supernatants in 1:1 ratio with 8 μg/mL polybrene.

- Incubate cells with virus mixture overnight (16-24 hours).

- Remove virus-containing medium and replace with fresh growth medium.

- Allow recovery for 24 hours before selection.

Dual Selection:

- Trypsinize cells and transfer to 140-mm dishes.

- Apply blasticidin (30 μg/mL) for 5 days followed by puromycin (4 μg/mL) for 3 days.

- Alternatively, apply both antibiotics simultaneously if cell viability remains high.

Induction Testing:

- Split selected cells into doxycycline-treated (3 μg/mL) and untreated controls.

- For Gaussia luciferase, sample media at 24, 48, and 72 hours for activity assays.

- For fluorescent reporters, analyze by FACS 48-72 hours post-induction.

- Calculate induction fold-change as ratio of induced/uninduced signal.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If induction is suboptimal, try doxycycline concentration gradients (0.1-10 μg/mL).

- For poor cell survival during dual selection, sequence the antibiotics or reduce concentrations.

- If background remains high, consider sequential infection with blasticidin selection before lentiviral transduction.

Implementing a Fluorescent Timer System for Monitoring Transcriptional Dynamics

The Timer-of-cell-kinetics-and-activity (Tocky) system enables analysis of transcriptional dynamics at single-cell resolution using a mutant mCherry fluorescent timer protein (Fast-FT) that irreversibly changes from blue to red fluorescence with a maturation half-life of 4.1 hours [34].

Materials:

- Fast-FT timer protein gene construct

- Lentiviral packaging system (psPAX2, pMD2.G)

- Flow cytometer with blue (excitation ~400nm) and red (excitation ~570nm) detection capabilities

- Appropriate tissue culture reagents for target cells

- Computational resources for machine learning analysis

Procedure:

- Vector Construction:

- Clone Fast-FT timer gene downstream of regulatory elements of interest

- Incorporate into lentiviral backbone with appropriate selection marker

- Validate timer function in control cells before proceeding

Cell Transduction and Selection:

- Produce lentiviral particles using standard protocols

- Transduce target cells at appropriate MOI to ensure single integration events

- Apply antibiotic selection if needed to establish stable lines

Time-Course Experiment:

- Apply experimental treatments or conditions to cells

- Harvest cells at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 6, 12, 24, 48 hours)

- Process for flow cytometry analysis using both blue and red channels

Data Acquisition:

- Collect minimum of 10,000 events per sample

- Export both blue and red fluorescence values for all cells

- Include appropriate controls (untransduced cells, single color compensations)

Machine Learning Analysis (TockyConvNet):

- Preprocess data: transform to Timer Angle and Timer Intensity [34]

- Convert fluorescence data to 2D "images" for convolutional neural network

- Train TockyConvNet model using Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping

- Identify group-specific feature cells representing distinct transcriptional dynamics

Interpretation Guidelines:

- Blue-dominant cells indicate recent transcriptional activation

- Red-dominant cells reflect historical expression with little recent activity

- Balanced blue-red signal suggests ongoing, sustained transcription

- Use TockyKmeansRF clustering to identify subpopulations with distinct dynamics

System Integration and Emerging Technologies

Advanced Delivery Systems for Genome Editing Applications

Beyond traditional reprogramming, temporal control is crucial for emerging genome editing technologies. The delivery of editing components represents a significant barrier to clinical translation. Current systems include:

Viral Delivery Systems:

- Lentiviral Vectors: Capable of loading large genetic material, engineered for increased safety with low risk of oncogene activation despite integrative nature [35].

- Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs): Well-standardized but limited DNA loading capacity, may cause off-target infections and require repetitive administration [35].

- Adenoviruses: Largest DNA loading capacity but high immunogenicity in human population [35].

Non-Viral Delivery Approaches:

- Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) for RNA delivery

- Polymer-based nanoparticles

- Physical methods (electroporation, microinjection)

Each delivery modality presents distinct advantages for temporal control, with non-viral methods typically offering more transient expression profiles suitable for precise temporal regulation of editing activity.

Machine Learning-Assisted Analysis of Transcriptional Dynamics

Recent advances integrate molecular biology with machine learning to decode complex temporal transcriptional patterns. The Tocky system combined with specialized computational approaches enables:

TockyKmeansRF Method:

- Integrates k-means clustering with Random Forest analysis

- Uses mean decrease Gini index to monitor model behavior

- Identifies subpopulations with distinct transcriptional dynamics

TockyConvNet Framework:

- Converts fluorescence data to 2D images for convolutional neural network analysis

- Employs Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) to identify key predictive regions

- Establishes continuous scoring system for quantitative phenotype analysis [34]

These approaches overcome limitations of manual gating, reducing arbitrariness and subjectivity while enhancing reproducibility in the analysis of dynamic gene expression patterns.

The toolkit for temporal control of gene expression has expanded dramatically beyond first-generation retroviral systems. Modern doxycycline-inducible systems offer remarkable induction ratios exceeding 200-fold with minimal background, while mRNA transfection enables precise, transient expression without genomic integration. Small molecule-controlled protein stability systems provide an additional layer of temporal precision. The integration of these technologies with advanced delivery systems and machine learning-assisted analysis creates unprecedented opportunities for investigating the timing of reprogramming factor expression.

Successful implementation requires careful system selection based on experimental goals, appropriate delivery methods for target cells, and robust validation across multiple parameters. The troubleshooting guides and protocols provided here address common challenges in establishing these systems, from minimizing background expression to achieving uniform induction across cell populations. As temporal control technologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly yield deeper insights into the dynamic processes governing cellular reprogramming and fate determination.

Harnessing Chromatin Accessibility Data with Tools like AME and diffTF for Factor Discovery and Ranking

In the context of researching the timing of reprogramming factor expression, profiling chromatin accessibility has emerged as a powerful strategy. Accessible chromatin regions represent the small fraction of the genome that is nucleosome-depleted and physically accessible for transcription factor (TF) binding, reflecting its regulatory capacity [36]. Technologies like ATAC-seq have simplified the process of mapping these accessible regions, providing a snapshot of the regulatory landscape of a cell [37] [36]. For scientists aiming to reprogram cells, a critical step is to identify the key transcription factors that can initiate this process. Methods that utilize chromatin accessibility data, such as AME (Analysis of Motif Enrichment) and diffTF, have been shown to systematically prioritize these reprogramming factor candidates, outperforming those that rely on gene expression data alone [38]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting and methodological guidance for employing these tools effectively in your reprogramming experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why should I use chromatin accessibility data instead of gene expression data to find reprogramming factors? Gene expression data can be confounded by post-transcriptional regulation and may not directly reflect a transcription factor's DNA-binding activity. In contrast, chromatin accessibility directly identifies regions of the genome that are open and primed for TF binding, providing a more direct readout of the regulatory state. Empirically, methods using chromatin accessibility have been proven superior for this task, identifying an average of 50–60% of known reprogramming factors within the top 10 candidates [38].

2. What is the difference between AME and diffTF? AME performs discriminative motif enrichment analysis, testing if known transcription factor binding motifs are statistically over-represented in your set of accessible regions compared to a background sequence set [38]. diffTF, on the other hand, calculates differential TF activity by integrating chromatin accessibility with a database of TF motifs to estimate the differential binding of TFs between two conditions [38]. While both use chromatin accessibility, AME is primarily a motif enrichment tool, whereas diffTF models differential TF activity.

3. How much ATAC-seq sequencing depth do I need for factor discovery? For robust identification of open chromatin regions, a minimum of 50 million mapped reads is recommended for mammalian systems. If your analysis plan includes more advanced applications like transcription factor footprinting, a deeper sequencing depth of 200 million mapped reads is advised [37].

4. My reprogramming experiment involves a rare cell type. Can I use these methods with low cell input? Yes. The ATAC-seq protocol itself can be performed on as few as 500 cells [37], and the subsequent computational analysis with tools like AME and diffTF is designed to work with the resulting data. The key is to ensure that your ATAC-seq data passes standard quality control metrics.

5. Among the various computational methods, which one is most recommended? A systematic evaluation of nine computational methods found that AME and diffTF provided the most robust performance for transcription factor recovery from chromatin accessibility data. The study identified these two as optimal methods for the systematic prioritization of transcription factor candidates [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Transcription Factor Candidate Recovery

Symptoms: Your analysis fails to identify known reprogramming factors or returns an implausible list of candidates.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor quality ATAC-seq data | Check FastQC reports and fragment size distribution plot. Look for a clear periodical pattern of nucleosome-free regions (<100 bp) and mono-nucleosomes (~200 bp) [37]. | Re-perform ATAC-seq ensuring high-quality, intact nuclei and optimal transposition reaction. |

| Suboptimal genomic region selection | Verify the number and characteristics of peaks called. | For motif enrichment with AME, use a stringent peak call set (e.g., the top 20,000–50,000 most accessible peaks) and a matched GC-content background [38]. |

| Incorrect tool parameterization | Review the tool's documentation for key parameters. | For diffTF, ensure you are correctly specifying the two conditions for comparison and using an appropriate statistical framework [38]. |

Problem 2: ATAC-Seq Data Quality Issues

Symptoms: Low unique mapping rate, high duplicate reads, or absence of the characteristic fragment size periodicity.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Over-digestion or under-digestion by transposase | Examine the fragment size distribution plot for the absence of a nucleosomal pattern [37]. | Titrate the amount of Tn5 transposase used and/or optimize the reaction time. |

| High mitochondrial reads | Check alignment statistics to see the percentage of reads mapped to the mitochondrial genome. | Increase the intensity of nuclei purification steps to reduce cytoplasmic contamination [37]. |

| PCR over-amplification | Use tools like Picard to check the fraction of duplicate reads. | Reduce the number of PCR cycles during library amplification. Incorporate dual-indexed primers to improve complexity [39]. |

Problem 3: Computational Processing Errors

Symptoms: Scripts fail with encoding errors, memory issues, or uninterpretable output.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| File encoding issues | Check for special characters in sequence headers or the file itself. | Ensure your FASTA/FASTQ files are saved in UTF-8 encoding. Use a script to clean headers of non-standard characters [40]. |

| Insufficient computational resources | Monitor memory (RAM) usage during job execution. | Peak calling and motif analysis are memory-intensive. Use a compute cluster or server with high RAM (e.g., 32GB+). |

| Incorrect file formats | Validate the format of your input files (e.g., BED, FASTA) with tool-specific validation commands. | Convert files to the correct format using tools like bedtools or Bioconductor packages. |

The following diagram illustrates the general analytical workflow for harnessing chromatin accessibility data to discover and rank reprogramming factors, integrating tools like AME and diffTF.

Performance Comparison of Computational Methods

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of various computational methods for reprogramming factor discovery, as identified in a systematic comparison. A key finding was that methods utilizing chromatin accessibility data consistently outperformed those based on gene expression [38].

| Method | Primary Data Type | Key Function | Performance Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| AME | Chromatin Accessibility | Motif Enrichment | Identified as an optimal method for robust transcription factor recovery [38]. |

| diffTF | Chromatin Accessibility | Differential TF Activity | Identified as an optimal method; higher correlation with ranked significance of factors [38]. |

| DeepAccess | Chromatin Accessibility | Sequence-based Prediction | Complex method with high performance [38]. |

| HOMER | Chromatin Accessibility | De novo & Known Motif Discovery | Widely adopted tool for finding enriched motifs [38]. |

| DREME | Chromatin Accessibility | De novo Motif Discovery | Discovers short, core motifs enriched in sequences [38]. |

| GarNet | Chromatin Accessibility & RNA-seq | Regulatory Network | Combines ATAC-seq and RNA-seq to link TFs to gene expression [38]. |

| CellNet | RNA-seq | Regulatory Network | Requires pre-existing network models; less applicable to new cell types [38]. |

| EBSeq | RNA-seq | Differential Expression | Ranks TFs based on differential expression between cell types [38]. |

Advanced Analysis: Reconstructing Regulatory Networks

After identifying candidate reprogramming factors, the next step is to understand how they might interact to regulate the cell's transcriptional program. This involves reconstructing transcriptional regulatory networks by integrating ATAC-seq data with other data types, such as RNA-seq.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and resources essential for conducting analysis of chromatin accessibility data for reprogramming factor discovery.

| Tool/Resource | Function | Role in Factor Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| ATAC-seq | Profiles genome-wide chromatin accessibility. | Generates the primary input data (peak files or sequences) for tools like AME and diffTF [37]. |

| MACS2 | Peak calling from sequencing data. | Identifies genomic regions that are significantly accessible, defining the sequences for motif analysis [37]. |

| AME (MEME Suite) | Discriminative motif enrichment analysis. | Tests if known transcription factor binding motifs are statistically over-represented in accessible regions [38]. |

| diffTF | Differential transcription factor activity analysis. | Computes a statistical measure of differential TF binding between two conditions using accessibility and motif data [38]. |

| HOMER | De novo motif discovery and enrichment. | Finds enriched motifs de novo or against a known motif database in sets of genomic regions [38]. |

| BWA-MEM / Bowtie2 | Sequence alignment to a reference genome. | Aligns sequenced reads to the genome, a critical pre-processing step before peak calling [37]. |

| FastQC | Quality control of sequencing data. | Provides an initial report on read quality, adapter contamination, and other potential issues [37]. |

Integrating chromatin accessibility data with robust computational methods like AME and diffTF provides a powerful, data-driven framework for identifying key transcription factors in cellular reprogramming experiments. By following the detailed protocols, troubleshooting guides, and best practices outlined in this technical support center, researchers can systematically overcome common challenges and confidently prioritize factor candidates. This approach directly informs the broader thesis of understanding the timing of reprogramming factor expression by revealing the initial regulatory landscape that these factors must engage with to direct cell fate changes.

This technical support guide is framed within the broader research thesis investigating the critical role of timing in reprogramming factor expression. The emergence of chemical reprogramming, which uses small-molecule cocktails to reverse cellular aging without genetic alteration, represents a paradigm shift in rejuvenation medicine [41]. Unlike genetic approaches that risk insertional mutagenesis and require precise control of transgene duration, chemical cocktails offer a non-integrative, titratable, and transient method to induce cellular reprogramming [42]. This guide provides detailed protocols, troubleshooting, and resources to help researchers master the temporal application of these cocktails, a key variable for achieving successful and safe cell rejuvenation without loss of cellular identity.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the core advantage of using chemical cocktails over viral vectors for reprogramming? Chemical cocktails provide a non-integrative and transient method for cellular reprogramming and rejuvenation. This eliminates the risk of insertional mutagenesis linked to viral vectors. The concentration and duration of the cocktail's action can be precisely tuned and withdrawn, allowing for superior temporal control over the reprogramming process, which is crucial for achieving partial, rather than full, reprogramming to a pluripotent state [41] [42].

Q2: My cells are not showing expected rejuvenation markers after 7c cocktail treatment. What could be wrong? This is often related to the health and age of your starting cell population. The efficacy of chemical reprogramming can be influenced by the donor's biological age. Furthermore, extended in vitro passaging of primary fibroblasts can rapidly increase their epigenetic age in culture, which may diminish the treatment's effect. Ensure you are using low-passage cells (e.g., ≤ 4 passages) to maintain a physiologically relevant aged phenotype for consistent results [42].

Q3: I am observing high cell toxicity with the 7c cocktail. How can I mitigate this? The full 7c cocktail is potent and can impact cell proliferation. Consider these steps:

- Titrate Dosage: Systemically lower the concentration of each component to find a tolerable yet effective dose.

- Simplify the Cocktail: Start with the 2c cocktail (containing only Repsox and tranylcypromine), which has been shown to be effective for some rejuvenation endpoints with less impact on proliferation [42].

- Shorten Exposure: Reduce the treatment duration and monitor for early markers of efficacy, such as changes in mitochondrial membrane potential.

Q4: How can I confirm that my chemical reprogramming experiment is successful without genetic tools? Employ functional and molecular assays to measure hallmarks of aging and rejuvenation.

- Functional Assays: Use assays like the Mito Stress Test on a Seahorse Analyzer to measure increases in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and spare respiratory capacity, key indicators of rejuvenation [42].

- Molecular Clocks: Utilize epigenetic or transcriptomic aging clocks to quantitatively measure the reduction in biological age of the treated cells compared to controls [41] [42].

- Metabolomic Analysis: Monitor for the reduction of aging-related metabolites [42].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Reprogramming Efficiency | Inadequate cocktail concentration or duration; poor cell health. | Titrate cocktail components; optimize treatment window; use low-passage, high-viability cells. |

| High Cell Death/Toxicity | Cocktail concentration too high; sensitive cell type. | Reduce component concentrations; try a simpler cocktail (e.g., 2c before 7c). |

| Inconsistent Results Between Batches | Variability in primary cell isolates; slight preparation differences in cocktail. | Standardize cell sourcing and passage number; prepare large, single-use aliquots of cocktail. |

| Failure to Reverse Aged Phenotype | Cells are too senescent; key pathways are unresponsive. | Pre-condition cells with a senolytic treatment; confirm cocktail activity via a positive control (e.g., increase in TMRM signal). |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Core Protocol: Partial Chemical Reprogramming of Mouse Fibroblasts

This protocol, adapted from multi-omics studies, details the treatment of mouse fibroblasts to induce a rejuvenated state [42].

1. Reagent Setup

- 7c Chemical Cocktail: Prepare stock solutions in appropriate solvents (e.g., DMSO or water) for Repsox (TGF-β inhibitor), tranylcypromine (LSD1 inhibitor), DZNep (EZH2 inhibitor), TTNPB (RA receptor agonist), CHIR99021 (GSK-3 inhibitor), forskolin (adenylyl cyclase activator), and valproic acid (HDAC inhibitor).

- 2c Chemical Cocktail: Prepare stocks for Repsox and tranylcypromine.

- Cell Culture Medium: Standard fibroblast growth medium.

2. Cell Preparation

- Isolate tail or ear fibroblasts from young (e.g., 4-month) and aged (e.g., 20-month) male C57BL/6 mice.

- Culture fibroblasts and use them at low passage number (≤ 4) to preserve age-related characteristics. Plate cells at an appropriate density for your assays 24 hours before treatment.

3. Chemical Treatment

- Add the 2c or 7c cocktail to the culture medium. A treatment duration of 4-6 days is typical for observing initial rejuvenation effects.

- Include a vehicle control (e.g., DMSO) of equal concentration to treated cells.

4. Outcome Assessment (After 4-6 days of treatment)

- Pluripotency Check: Assess alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity. Note that 2c treatment may increase AP activity, while 7c may not, indicating different mechanisms [42].

- Mitochondrial Function:

- Membrane Potential: Use TMRM fluorescence to measure basal mitochondrial membrane potential. An increase is an early indicator of successful rejuvenation.

- Oxidative Phosphorylation: Perform a Seahorse Mito Stress Test to measure Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR). A significant increase in spare respiratory capacity is a key expected outcome of 7c treatment.