UMI Barcoding in Stem Cell scRNA-seq: A Complete Guide to Quantitative Analysis and Heterogeneity Resolution

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) with Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) has become an indispensable tool for dissecting the complex heterogeneity of stem cell populations, tracing lineage commitment, and understanding the molecular...

UMI Barcoding in Stem Cell scRNA-seq: A Complete Guide to Quantitative Analysis and Heterogeneity Resolution

Abstract

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) with Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) has become an indispensable tool for dissecting the complex heterogeneity of stem cell populations, tracing lineage commitment, and understanding the molecular basis of self-renewal and differentiation. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of UMI barcoding, from its role in correcting amplification bias to its statistical advantages over read counts. It details practical methodological applications for studying stem cell dynamics, explores common troubleshooting and optimization strategies for data quality control, and offers a comparative validation of analysis workflows and emerging multiplexing technologies. By synthesizing established knowledge with the latest methodological advances, this guide aims to empower robust and quantitative single-cell transcriptomic studies in stem cell biology.

Demystifying UMI Barcoding: The Foundation for Quantitative scRNA-seq in Stem Cell Biology

In single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), the ultimate goal is to accurately quantify the absolute number of RNA transcript molecules within individual cells [1]. This quantification is fundamentally challenged by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification step, an essential process in library preparation that ensures sufficient material for sequencing [2] [1]. Amplification bias occurs because certain sequences are preferentially amplified over others during PCR, leading to overrepresentation of particular transcripts in the final sequencing library that does not reflect their original biological abundance [3] [1]. In stem cell studies, where understanding subtle differences in heterogeneous populations is crucial, this bias can distort the true transcriptome landscape, leading to inaccurate biological interpretations.

Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) are short, random oligonucleotide sequences that provide an elegant solution to this problem [4] [3]. Incorporated into each mRNA molecule during the initial library preparation steps—before any amplification occurs—UMIs uniquely tag each original transcript [1]. All PCR-amplified copies derived from the same original molecule will carry the identical UMI sequence. During bioinformatic analysis, reads sharing the same UMI and mapping to the same genomic locus are identified as PCR duplicates and collapsed into a single digital count [3] [5]. This process effectively removes the amplification bias, enabling researchers to count the number of original molecules directly, thus transforming analog, biased read counts into accurate, digital transcript counts [1].

Table 1: Core Components of the UMI Digital Counting Principle

| Component | Function | Impact on Quantification |

|---|---|---|

| UMI Tagging | Labels each original mRNA molecule with a unique random barcode before PCR amplification [1]. | Enables tracing of molecule ancestry through amplification process. |

| PCR Amplification | Generates sufficient copies of tagged molecules for sequencing [2]. | Introduces quantitative bias that UMI correction is designed to remove. |

| Computational Deduplication | Collapses reads sharing UMI and alignment coordinates into a single count [3] [5]. | Converts analog read counts into digital molecular counts, eliminating amplification noise. |

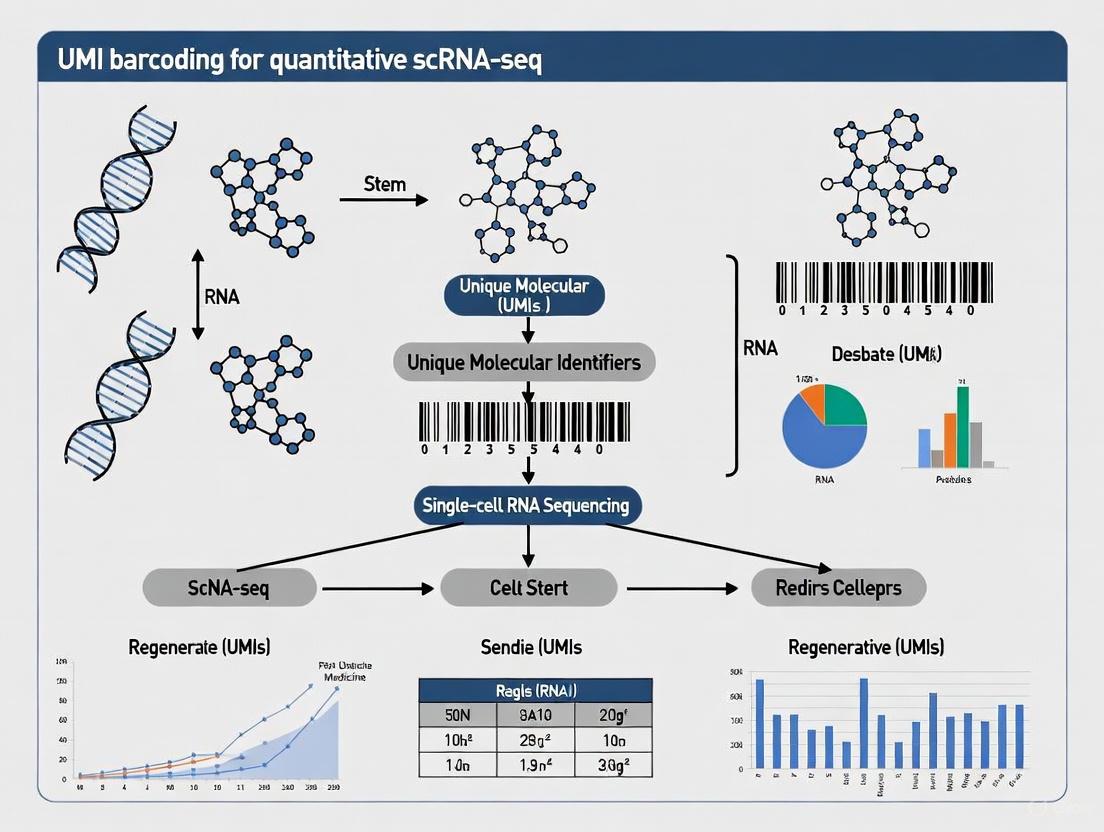

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of how UMIs enable digital counting by correcting for PCR amplification bias.

Key Technological Protocols and Reagent Solutions

Experimental Protocol for UMI-Based scRNA-seq

The successful implementation of UMI-based digital counting relies on a meticulously followed experimental protocol. The following steps outline a standard workflow, such as that used in 10x Genomics platforms, which have been recently advanced by GEM-X technology [6].

- Single-Cell Suspension Preparation: A high-viability single-cell or nucleus suspension is prepared from stem cell cultures or tissues. For tissues difficult to dissociate, single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) is a viable alternative that minimizes artificial stress responses [2].

- Gel Bead and Reagent Loading: The cell suspension is combined with lysis buffer and loaded onto a microfluidic chip, along with Gel Beads and partitioning oil. The GEM-X chips generate twice as many Gel Beads-in-emulsion (GEMs) as previous versions, reducing multiplet rates and improving efficiency [6].

- GEM Generation and Cell Partitioning: Within the Chromium instrument, the mixture is partitioned into nanoliter-scale GEMs. The redesigned GEM-X architecture utilizes oil flow to facilitate GEM formation, enabling faster (6-minute) partitioning and recovery of up to 80% of input cells [6].

- Cell Lysis and Barcoding: Inside each GEM, the single cell is lysed, releasing its RNA. The Gel Bead dissolves, exposing oligonucleotides containing several key functional regions [6]:

- A 10x Barcode unique to each Gel Bead, marking every transcript from the same cell.

- A Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI), a random 12-base sequence that uniquely tags each individual mRNA molecule.

- A Poly(dT) sequence for capturing the poly-adenylated tail of mRNA.

- Reverse Transcription: The primed RNA undergoes reverse transcription within the GEM, creating barcoded cDNA where all copies from a single original molecule share the same UMI [2] [6].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: The barcoded cDNA is purified, amplified via PCR, and prepared into a sequencing library. The library is then sequenced on a high-throughput platform [2].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The UMI scRNA-seq workflow depends on several critical reagents and solutions, each playing a vital role in the digital counting process.

Table 2: Key Reagents for UMI scRNA-seq Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Critical Function | Technical Note |

|---|---|---|

| Gel Beads | Microbeads coated with barcoded oligos (10x Barcode, UMI, Poly(dT)) for mRNA capture and tagging [6]. | GEM-X technology uses optimized beads for increased sensitivity, detecting up to 98% more genes [6]. |

| Partitioning Oil & Microfluidic Chips | Creates nanoliter-scale reaction vessels (GEMs) for single-cell isolation and barcoding [6]. | GEM-X chip architecture improves GEM generation, halves multiplet rates (to 0.4%), and increases throughput to 20,000 cells per channel [6]. |

| Reverse Transcription (RT) Reagents | Enzymes and buffers to convert captured mRNA into stable, barcoded cDNA [2]. | Must have high efficiency to maximize transcript capture, a key factor for detecting lowly expressed genes in stem cells. |

| UMI Adapters/Oligos | Short, random nucleotide sequences (e.g., 10nt = ~1 million unique combinations) that label individual molecules [1]. | Can be incorporated via RT primers or template-switching oligos. Must have sufficient complexity to avoid UMI saturation [1]. |

Computational Analysis and Error Correction for UMI Data

Bioinformatic Processing of UMI Counts

Following sequencing, raw data must be processed to generate an accurate cell-by-gene digital expression matrix. A standard pipeline involves the following key steps, with UMI error correction being particularly critical.

- Demultiplexing and Alignment: Sequencing reads are demultiplexed using the 10x Barcode to assign reads to their cell of origin and then aligned to a reference genome [5].

- UMI Deduplication (Collapsing): For each cell, reads that align to the same genomic coordinate and share the same UMI sequence are identified and collapsed into a single count, representing one original molecule [3] [5].

- UMI Error Correction: This step is crucial for accurate quantification. PCR amplification and sequencing can introduce errors (substitutions, insertions, deletions) into the UMI sequences themselves, creating artifactual UMIs that inflate transcript counts [4] [3]. Multiple computational strategies exist to correct these errors:

- Network-Based Methods (e.g., UMI-tools): These tools model sequencing errors in UMIs by grouping similar UMIs at the same genomic locus into networks. Methods like "directional" use read counts and edit distances to resolve which UMIs are likely errors derived from a more abundant parent UMI [3].

- Homotrimeric Nucleotide Blocks: A recent advanced method synthesizes UMIs using blocks of three identical nucleotides (homotrimers). Errors can be corrected via a 'majority vote' within each block, significantly improving counting accuracy over traditional monomeric UMIs, especially with increasing PCR cycles [4].

The diagram below illustrates the logical process of UMI deduplication and error correction.

Quantitative Impact of PCR Errors and Correction

The necessity of robust UMI error correction is underscored by empirical data showing how PCR amplification directly introduces inaccuracies in transcript counting.

Table 3: Impact of PCR Cycles and Error Correction on UMI Accuracy

| Experimental Condition | Finding | Implication for scRNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Increasing PCR Cycles | A controlled experiment showed a substantial increase in errors within common molecular identifiers (CMIs) as PCR cycles increased from 20 to 25 to 35 [4]. | Protocols should use the minimum number of PCR cycles necessary to maintain library complexity and avoid inflating UMI counts. |

| Homotrimer vs. Monomer UMI Correction | After 25 PCR cycles, homotrimer UMI correction achieved ~96-100% accuracy, outperforming monomer-based tools (UMI-tools, TRUmiCount) which left a significant error rate [4]. | Advanced UMI designs and correction algorithms are critical for absolute molecular counting, especially in sensitive applications. |

| Effect on Differential Expression | In a splicing perturbation experiment, 7.8% of differentially expressed genes were discordant between monomer UMI-tools and homotrimer correction, with homotrimer results yielding more biologically relevant gene ontology terms [4]. | Inaccurate UMI correction can lead to false positives/negatives in downstream analysis, potentially misleading biological conclusions. |

Application in Stem Cell Research

Within the context of stem cell studies, UMI-based scRNA-seq has become an indispensable tool for dissecting cellular heterogeneity, defining differentiation trajectories, and identifying rare subpopulations [7].

- Resolving MSC Heterogeneity and Defining Markers: Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells (MSCs) are known to be highly heterogeneous. SCS technology, empowered by accurate UMI counting, has been pivotal in moving beyond the classical surface marker definitions (e.g., CD105, CD73, CD90) to reveal distinct transcriptional subpopulations within MSC cultures from bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord [7]. This allows for a more precise functional characterization of MSC subtypes.

- Mapping Differentiation Trajectories: Understanding the multi-lineage differentiation potential of MSCs into adipocytes, osteocytes, and chondrocytes is a central research focus. UMI-based scRNA-seq enables researchers to study the transcriptome dynamics of individual cells during differentiation, revealing the sequence of transcriptional changes and identifying key regulatory pathways and transient cell states that are masked in bulk analyses [7].

- Characterizing Immunomodulatory Functions: The immunomodulatory capacity of MSCs is a key mechanism in their therapeutic application. By analyzing the interaction between MSCs and immune cells at a single-cell resolution, researchers can identify the specific MSC subclusters that express critical regulatory molecules and unravel the complex cellular crosstalk that underlies their immunomodulatory function [7].

The application of advanced UMI technologies like GEM-X, which offers increased sensitivity and cell recovery, is particularly beneficial in stem cell research. It improves the detection of rare transcripts and lowly expressed regulatory genes, and enhances the capture of rare stem cell subpopulations or cells from precious samples like small tissue biopsies, thereby empowering deeper insights into stem cell biology [6].

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has transformed our ability to dissect cellular heterogeneity, a crucial feature in stem cell studies where populations are often diverse and dynamic. The quantitative accuracy of scRNA-seq, however, hinges on advanced molecular barcoding strategies that enable researchers to trace each sequenced transcript back to its cell of origin while controlling for technical artifacts. These barcoding systems are particularly vital for stem cell research, where accurately quantifying expression differences between rare stem cell sub-populations can reveal critical insights into differentiation pathways and regulatory mechanisms.

Barcodes in scRNA-seq are short nucleotide sequences that serve as unique labels during library preparation [8]. The core barcode ecosystem comprises three principal components: Cell Barcodes that tag all transcripts from an individual cell, Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) that label individual mRNA molecules, and Sample Barcodes that enable multiplexing of multiple libraries. Together, this tripartite system transforms complex sequencing data into quantitatively accurate, cell-resolved transcriptomes by providing information about cellular origin, molecular identity, and experimental sample [8] [9]. Understanding the distinct functions, applications, and implementation of each barcode type is foundational to designing robust scRNA-seq experiments in stem cell research.

Core Barcode Components: Definitions and Distinctive Functions

Cell Barcodes

Cell Barcodes are short nucleotide sequences (~16 base pairs) used to "label" all sequences that originate from a single cell source [8]. During single-cell isolation—whether through droplet-based systems (e.g., 10x Genomics, inDrops) or well-based methods—each cell is co-encapsulated with a bead containing a unique cell barcode sequence. During reverse transcription, this barcode is incorporated into all cDNA molecules derived from that specific cell [8] [10]. Following sequencing and bioinformatic processing, sequences sharing the same cell barcode are grouped together as having originated from the same cell, enabling the reconstruction of individual cell transcriptomes from a pooled library.

The primary function of cell barcodes is to enable multiplexing at the cellular level, allowing thousands of cells to be sequenced simultaneously in a single run while maintaining the ability to deconvolute the data back to individual cells [11]. In droplet-based systems, the theoretical diversity of cell barcode libraries is immense—reaching up to 147,456 unique barcodes in some platforms—ensuring a very low probability of two cells receiving the same barcode [11]. However, a key technical consideration is the occurrence of multiplets or doublets, where two or more cells are coincidentally encapsulated together and receive the same cell barcode, potentially leading to misinterpretation of cellular identities [12]. The empirical "technical doublet" rate is often determined by mixing cells from two different species and monitoring barcode purity [11].

Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs)

Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) are short, random nucleotide sequences (typically 4-10 base pairs) that serve as molecular barcodes for quality control and quantitative accuracy [8] [9]. Unlike cell barcodes, which are identical for all transcripts from the same cell, each individual mRNA molecule is tagged with a unique UMI during the reverse transcription process [8]. This molecular-level labeling enables bioinformatic correction of amplification biases that inevitably occur during library preparation.

The core function of UMIs is to distinguish between biological duplicates (multiple transcripts from the same original mRNA molecule) and technical duplicates (multiple reads generated through PCR amplification of the same cDNA fragment) [8] [10]. During data processing, reads sharing the same cell barcode, gene assignment, and UMI are collapsed into a single count, representing one original mRNA molecule [8]. This UMI collapsing process mitigates the effects of PCR amplification bias, where some molecules are amplified more efficiently than others, and provides a more accurate quantitative representation of the true molecular count in the original sample [9]. This is especially crucial in stem cell studies where detecting subtle expression differences in key regulatory genes can have significant biological implications.

UMIs also enhance variant detection sensitivity by helping distinguish true biological variants from errors introduced during amplification or sequencing [8] [9]. Since each original molecule is uniquely tagged, sequencing errors can be identified and filtered out, enabling more reliable detection of rare variants and improving the overall quality of quantitative gene expression data [13].

Sample Barcodes (Indexes)

Sample Barcodes (also known as sample indexes) are sequences used to multiplex multiple libraries during sequencing runs [9]. Unlike cell barcodes and UMIs, which operate at the cellular and molecular levels respectively, sample barcodes are added during library preparation and are identical for all sequences derived from the same library. After sequencing, these barcodes enable bioinformatic demultiplexing, where pooled sequences are sorted computationally into their original sample groups.

The primary function of sample barcodes is cost efficiency and experimental design flexibility, allowing researchers to sequence multiple samples simultaneously on the same flow cell while maintaining sample identity [9]. With the advent of unique dual indexes (UDIs), where each sample receives a unique combination of two barcodes, the potential for index hopping (misassignment of reads to wrong samples) is significantly reduced, further enhancing data integrity [9].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Barcode Types in scRNA-seq

| Feature | Cell Barcodes | UMIs | Sample Barcodes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Demultiplex cells | Quantify molecules | Demultiplex samples |

| Sequence Length | ~16 bp [8] | 4-10 bp [8] | Varies (typically 6-10 bp) |

| Scope of Application | Individual cell | Individual mRNA molecule | Entire library/sample |

| Key Applications | Single-cell resolution, cell tracking [8] | PCR duplicate removal, quantitative analysis [8] [9] | Multiplexing, cost reduction [9] |

| Added During | Cell isolation/encapsulation | Reverse transcription | Library preparation |

| Bioinformatic Processing | Cell calling, doublet detection [12] | UMI collapsing, error correction [8] | Demultiplexing |

Barcoding Technologies and Experimental Workflows

Single-cell RNA sequencing technologies have evolved substantially, with current platforms predominantly utilizing droplet-based or well-based approaches for cell barcoding [14]. Droplet-based systems (e.g., 10x Genomics, inDrops) employ microfluidics to co-encapsulate individual cells with barcoded beads in nanoliter-scale droplets, achieving high throughput of thousands to millions of cells [11] [14]. Well-based methods (e.g., CEL-Seq2, SMART-Seq) distribute cells into multiwell plates containing unique barcodes, offering greater flexibility but lower throughput [10] [14].

The inDrop platform exemplifies a droplet-based approach, encapsulating cells into droplets with lysis buffer, reverse transcription reagents, and barcoded oligonucleotide primers [11]. Each barcoded hydrogel microsphere carries covalently coupled, photo-releasable primers encoding one of thousands of barcodes. Similarly, the CEL-Seq2 protocol employs a paired-end sequencing approach where Read1 contains the barcoding information (cell barcode and UMI) followed by a polyT tail, while Read2 contains the actual transcript sequence [10].

Detailed Protocol: CEL-Seq2 Barcoding Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for barcode incorporation in scRNA-seq protocols like CEL-Seq2:

The wet-lab workflow begins with single-cell isolation, where a cell suspension is partitioned into individual compartments [14]. For droplet-based methods, this occurs through microfluidic encapsulation; for well-based methods, through fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or limiting dilution. Next, cell lysis releases mRNA, which is captured by barcoded primers containing three functional elements: the cell barcode, a UMI, and a poly-dT sequence that binds to the mRNA poly-A tail [8] [10]. During reverse transcription, these primers generate barcoded cDNA. The cDNA is then amplified, sample barcodes are added during library preparation, and the pooled libraries are sequenced [10]. The subsequent bioinformatic processing involves demultiplexing samples by sample barcodes, grouping reads by cell barcodes, and collapsing duplicate reads by UMIs to generate accurate quantitative expression matrices [8] [10].

Bioinformatic Processing and Data Analysis

Barcode Extraction and Processing Pipeline

Following sequencing, bioinformatic processing of barcodes involves multiple critical steps to transform raw sequencing data into a quantitative gene expression matrix. The first step is demultiplexing, where sequences are assigned to their original samples based on sample barcodes [9]. Next, barcode extraction occurs, where cell barcodes and UMIs are identified from the sequencing reads—typically from Read1 in paired-end protocols like CEL-Seq2 [10].

A crucial quality control step is barcode validation, where cell barcodes are filtered against a whitelist of known valid barcodes to exclude those with sequencing errors [10]. For UMI processing, error correction is performed to account for sequencing errors, typically by clustering similar UMIs (within a certain Hamming distance) and collapsing them [12]. The final and most critical step is UMI deduplication, where reads sharing the same cell barcode, gene assignment, and UMI are collapsed into a single count, representing one original mRNA molecule [8] [10]. This process effectively removes PCR duplicates, providing a digital count of transcript molecules per gene per cell.

Statistical Considerations for UMI Count Data

Unique statistical properties distinguish UMI-count data from read-count data in scRNA-seq analysis. UMI counts follow a negative binomial distribution rather than requiring more complex zero-inflated models [13]. Research has demonstrated that while read-count measurements often necessitate zero-inflated negative binomial models to account for excess zeros, UMI counts are adequately modeled by a standard negative binomial distribution, with a significant proportion of genes even following a Poisson distribution [13]. This statistical simplicity reflects the reduced technical noise in UMI-based protocols and has important implications for differential expression analysis in stem cell studies.

For differential expression analysis of UMI count data, methods based on the negative binomial model with independent dispersions (NBID) have shown superior performance in controlling false discovery rates while maintaining good power [13]. This is particularly relevant in stem cell research where accurately detecting subtle expression changes in key regulatory genes can have significant biological implications.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Read-Count vs. UMI-Count Data Characteristics

| Characteristic | Read-Count Data | UMI-Count Data |

|---|---|---|

| Amplification Bias | High sensitivity to amplification biases [13] | Reduced impact of amplification biases [13] |

| Statistical Distribution | Often requires zero-inflated models [13] | Better fit to negative binomial distribution [13] |

| Percentage of Genes Following Poisson | 2.6% (range: 1.0-4.1%) [13] | 80.2% (range: 65.7-95.1%) [13] |

| Goodness of Fit to Negative Binomial | 14.2% reject NB model (range: 1.1-35.3%) [13] | 0.1% reject NB model (range: 0-0.4%) [13] |

| Recommended DE Analysis Method | Zero-inflated negative binomial models [13] | Negative binomial with independent dispersions (NBID) [13] |

Advanced Applications in Stem Cell Research

Resolving Stem Cell Heterogeneity

The integration of barcoding technologies has dramatically advanced stem cell research by enabling the resolution of cellular heterogeneity within seemingly homogeneous populations. In a landmark study profiling mouse embryonic stem cells, droplet-based barcoding of thousands of cells revealed population structure and the heterogeneous onset of differentiation after leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) withdrawal [11]. The high-throughput nature of barcoded scRNA-seq allowed researchers to identify rare sub-populations expressing markers of distinct lineages that would be difficult to detect when profiling only a few hundred cells [11].

Barcoding technologies have further enabled the investigation of correlation structures in gene expression across entire stem cell populations, revealing how key pluripotency factors fluctuate in a coordinated manner [11]. During differentiation, dramatic changes in these correlation structures occur, resulting from asynchronous inactivation of pluripotency factors and the emergence of novel cell states [11]. Such insights would be impossible without the quantitative accuracy provided by UMI-based counting and the cellular resolution enabled by cell barcoding.

Lineage Tracing and Synthetic Barcoding

Beyond transcriptome quantification, synthetic DNA barcodes have emerged as powerful tools for lineage tracing in stem cell biology. Recent approaches use heritable synthetic DNA barcodes to reconstruct cell lineage relationships alongside transcriptomic profiling [12]. These methods enable researchers to answer fundamental questions about stem cell fate decisions, clonal dynamics, and developmental trajectories.

An innovative application of synthetic barcodes is the identification of "ground-truth singlets" in scRNA-seq datasets [12]. The "singletCode" framework leverages the fact that each synthetically barcoded cell possesses a unique DNA sequence before scRNA-seq processing, enabling definitive identification of true single cells and accurate simulation of doublets for benchmarking computational methods [12]. This approach is particularly valuable in stem cell research where cell aggregation or similar transcriptional states can challenge conventional doublet detection methods.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Barcoding

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Barcoded Beads | Delivery of cell barcodes and UMIs to individual cells | 10x Genomics GemCode, inDrop Barcoded Hydrogel Microspheres [11] |

| Barcoded Primers | Reverse transcription primers containing barcodes | CEL-Seq2 barcoded primers [10] |

| Sample Indexing Kits | Multiplexing samples in sequencing runs | Illumina Indexing Kits [9] |

| Barcode Whitelists | Quality control of cell barcodes | 10x Genomics barcode whitelists [10] |

| UMI-Tools | Bioinformatic processing of UMI data | UMI extraction, error correction, deduplication [10] |

| Synthetic Barcode Libraries | Lineage tracing and singlet identification | FateMap, ClonMapper, SPLINTR, LARRY [12] |

The tripartite barcoding system—comprising cell barcodes, UMIs, and sample barcodes—forms the technological foundation of quantitative single-cell RNA sequencing. Each component addresses distinct challenges in single-cell analysis: cell barcodes enable multiplexing at cellular resolution, UMIs provide molecular-level quantification by correcting for amplification biases, and sample barcodes allow efficient library multiplexing. For stem cell researchers, understanding these core components and their integrated function is crucial for designing robust experiments, interpreting data accurately, and advancing our understanding of stem cell biology at single-cell resolution. As barcoding technologies continue to evolve, particularly with the integration of synthetic barcodes for lineage tracing, they will undoubtedly unlock new dimensions in the study of stem cell heterogeneity, fate decisions, and regulatory mechanisms.

In single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) studies of stem cells, Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) have transitioned from a technical refinement to an essential component for quantitative accuracy. UMIs are short, random oligonucleotide barcodes that tag individual mRNA molecules before PCR amplification, enabling precise molecule counting and distinguishing biological signal from technical artifacts [3] [9]. In stem cell research—where resolving subtle heterogeneity, identifying rare transitional states, and accurately tracing lineages are paramount—UMIs provide the mathematical foundation for distinguishing true biological variation from PCR amplification bias and sequencing errors [15]. Without UMI incorporation, attempts to quantify gene expression across heterogeneous stem cell populations remain semi-quantitative at best, as PCR duplicates artificially inflate counts for highly expressed genes and obscure true transcript diversity [16]. This technical note details the essential methodologies and applications that make UMIs non-negotiable for advanced stem cell research, providing structured protocols and analytical frameworks for leveraging their full potential.

Resolving Cellular Heterogeneity in Complex Stem Cell Populations

The Problem of PCR Amplification Bias

Stem cell populations, even those derived from clonal origins, demonstrate remarkable transcriptional heterogeneity that can reflect differential potency, metabolic states, or early lineage priming. Conventional scRNA-seq without UMIs struggles to accurately resolve this heterogeneity because PCR amplification during library preparation generates duplicate reads from original mRNA molecules [3]. These duplicates do not represent distinct biological molecules but rather technical artifacts that skew expression estimates. In studies of glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs), for instance, this amplification bias can obscure critical differences between stem-like states and more differentiated populations, potentially masking therapeutically relevant subpopulations [17].

UMI-Based Error Correction and Deduplication

UMIs solve this fundamental problem by providing a unique tag for each original molecule prior to amplification. Through UMI deduplication bioinformatics processes, reads sharing both genomic coordinates and identical UMIs are identified as technical replicates deriving from a single molecule, enabling accurate quantification of original transcript numbers [3] [18]. Advanced tools like UMI-tools and UMI-nea implement network-based clustering methods that account for sequencing errors in UMI sequences themselves—a common issue that can otherwise create artifactual UMIs and inflate diversity estimates [3] [18]. These tools model sequencing errors and strategically group similar UMIs that likely originated from the same source molecule, significantly improving quantification accuracy [3].

Diagram 1: UMI-integrated scRNA-seq workflow for stem cell studies. The process begins with a heterogeneous stem cell population, incorporates UMIs during reverse transcription, and culminates in accurate transcript quantification after computational deduplication.

Application in Identifying Stem Cell States

The power of UMI-based resolution is particularly evident in studies of cellular plasticity. Research on glioblastoma stem cells has demonstrated that cells expressing stem cell-associated surface markers (CD133, CD15, CD44, A2B5) do not represent fixed hierarchical entities but rather plastic states that most cancer cells can adopt in response to microenvironmental cues [17]. Without UMIs to provide accurate single-cell quantification, the dynamic nature of these states and their rapid interconversion would be difficult to capture with confidence. UMI-enabled scRNA-seq revealed that all GBM subpopulations—regardless of surface marker expression—retained stem cell properties and tumorigenic potential, fundamentally challenging hierarchical stem cell models [17].

Detecting Rare Stem Cell Populations with Confidence

Technical Limitations in Rare Cell Detection

The reliable identification of rare stem cell populations—such as quiescent stem cells, transitional intermediates, or therapy-resistant precursors—represents a significant challenge in stem cell biology. These populations often constitute less than 1% of total cells yet possess critical functions in tissue regeneration, cancer recurrence, and developmental processes. Conventional sequencing approaches struggle to distinguish true biological rare populations from technical artifacts caused by sequencing errors and PCR amplification bias, especially when analyzing low-input samples [19].

Enhanced Sensitivity with Molecular Barcoding

Dual-molecular barcode sequencing technologies significantly enhance sensitivity for detecting rare variants and low-abundance transcripts. In a study of tumor and cell-free DNA, molecular barcode sequencing enabled detection of variants with allele fractions as low as 0.17%—a sensitivity level unattainable with conventional non-UMI approaches [19]. This precision is equally valuable in stem cell research for identifying rare subpopulations defined by unique transcriptional signatures. The UMI-based approach allows researchers to set statistically rigorous thresholds for rare population identification, distinguishing true biological signals from technical noise with high confidence [19] [18].

Experimental Design Considerations

For optimal detection of rare stem cell populations, specific experimental design considerations are essential:

- UMI Length and Complexity: Longer UMIs (12-18bp for short-read sequencing) reduce the probability of "UMI collisions" where distinct molecules receive identical barcodes [18]

- Sequencing Depth: Increased sequencing depth compensates for low cellular abundance while UMI deduplication prevents artificial inflation from PCR duplicates

- Cell Number: Capturing sufficient cell numbers ensures adequate sampling of rare populations while maintaining single-cell resolution

- Bioinformatic Processing: Tools like UMI-nea that use Levenshtein distance (accounting for insertions/deletions) rather than just Hamming distance (substitutions only) provide more accurate error correction, especially valuable in long-read sequencing applications [18]

Lineage Tracing and Trajectory Reconstruction

Uncovering Developmental Hierarchies

Stem cell differentiation follows complex trajectories with branching points that define lineage commitment. UMI-enhanced scRNA-seq enables powerful computational reconstruction of these developmental pathways through pseudotime analysis [20]. By accurately quantifying transcriptomes without PCR distortion, UMIs provide the clean data necessary for algorithms to order cells along differentiation trajectories, identify branch points, and uncover genes driving fate decisions [20]. This approach has been successfully applied to diverse systems, from hematopoietic stem cell differentiation to the branching lineages in colonic epithelium, where absorptive and secretory cells diverge from common progenitors [21].

RNA Velocity and Beyond

Recent methodological advances like RNA velocity leverage UMI-based quantification to predict future cell states from single-cell snapshots [20]. By comparing the ratio of unspliced to spliced mRNAs—a measurement requiring accurate quantification of both forms—RNA velocity infers the direction and pace of cellular state transitions. For stem cell biologists, this enables not just observation of current states but prediction of developmental futures, identifying which stem cells are poised to differentiate and along which lineages [20]. When combined with UMI-based lineage barcoding that permanently marks cells and their progeny, these approaches provide a comprehensive view of stem cell lineage relationships in developing systems [20].

Diagram 2: UMI-enabled lineage trajectory reconstruction in stem cell differentiation. Accurate transcriptome quantification allows mapping of differentiation pathways and prediction of lineage commitment through RNA velocity analysis.

Essential Protocols for UMI Implementation in Stem Cell Studies

Wet-Lab Protocol: UMI Integration in scRNA-seq Library Preparation

Materials Required:

- Commercially available UMI-containing scRNA-seq kits (e.g., 10x Genomics, Parse Biosciences)

- Stem cell population of interest in single-cell suspension

- Laboratory equipment: microcentrifuge, thermal cycler, magnetic separator

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Cell Viability Assessment: Confirm >90% viability using trypan blue exclusion or similar method.

Single-Cell Partitioning and Lysis:

- Load cells following manufacturer's recommendations (targeting 5,000-10,000 cells)

- Ensure proper lysis to release RNA while maintaining cell integrity

Reverse Transcription with UMI Barcoding:

- Perform reverse transcription immediately after lysis

- UMI incorporation occurs automatically in commercial systems via barcoded beads

cDNA Amplification and Library Construction:

- Amplify with limited PCR cycles (typically 12-16) to minimize bias

- Incorporate platform-specific sequencing adapters

Quality Control and Sequencing:

- Assess library quality (Bioanalyzer/Fragment Analyzer)

- Sequence with sufficient depth (≥50,000 reads/cell recommended for heterogeneous stem cell populations)

Critical Considerations:

- For stem cell populations with extreme size variation (e.g., hematopoietic vs. mesenchymal stem cells), optimize cell loading concentration

- Include extraction controls to monitor background RNA contamination

- For rare populations (<1%), consider targeted enrichment approaches

Computational Protocol: UMI Deduplication and Analysis

Software Requirements:

- UMI processing tools (UMI-tools, UMI-nea, Calib)

- Single-cell analysis suite (Seurat, Scanpy, Monocle)

- Computing resources (minimum 16GB RAM for datasets <10,000 cells)

Processing Pipeline:

FASTQ Preprocessing:

- Extract UMIs from read sequences

- Trim adapter sequences and low-quality bases

Read Alignment:

- Align to reference genome using Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) or similar

- Generate gene count matrix incorporating UMIs

UMI Deduplication:

- For each cell, group reads by genomic coordinates

- Cluster UMIs using edit distance threshold (typically 1-2 bases)

- Apply directional network-based methods to resolve complex UMI groups [3]

Downstream Analysis:

- Normalize UMI counts across cells

- Perform dimensionality reduction and clustering

- Conduct differential expression and trajectory analysis

Troubleshooting Notes:

- High UMI error rates may indicate poor library quality or insufficient UMI complexity

- Adjust clustering parameters for different UMI lengths and sequencing depths

- Validate rare population findings with orthogonal methods when possible

Research Reagent Solutions for UMI-Enhanced Stem Cell Studies

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for UMI-Based Stem Cell Research

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Key Features for Stem Cell Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Twist UMI Adapter System | Ligation-based UMI incorporation | Compatible with low-input samples; enables detection of rare variants in heterogeneous populations [22] |

| 10x Genomics Single Cell Gene Expression | Droplet-based scRNA-seq with UMIs | High cell throughput ideal for capturing rare stem cell subpopulations; integrated workflow |

| Illumina UMI Adaptors | Sample preparation for UMI sequencing | Reduces false-positive variant calls; increases sensitivity for low-frequency transcripts [9] |

| QIAGEN UMI-nea Bioinformatics Tool | Computational UMI deduplication | Levenshtein distance accounting for indels; robust performance across sequencing platforms [18] |

| UMI-tools | Network-based UMI grouping | Directional method resolves complex UMI networks; improves quantification accuracy [3] |

The integration of UMIs into stem cell scRNA-seq workflows represents a fundamental advancement that transforms qualitative observations into quantitative measurements. By eliminating PCR amplification bias and enabling precise molecular counting, UMIs provide the technical foundation necessary to resolve stem cell heterogeneity, identify rare populations with statistical confidence, and accurately reconstruct lineage trajectories. As stem cell research increasingly focuses on dynamic processes, rare transitional states, and therapeutic applications, the implementation of UMI-based methodologies becomes not merely advantageous but essential. The protocols and frameworks outlined herein provide a pathway for researchers to leverage these powerful tools, ensuring that technical limitations do not constrain biological discovery in the complex landscape of stem cell biology.

Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) barcoding has revolutionized quantitative single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) in stem cell studies by enabling accurate transcript counting. This technology mitigates amplification bias by tagging individual mRNA molecules, allowing bioinformatic removal of PCR duplicates. A critical challenge in analyzing the resulting UMI count data involves selecting appropriate statistical models that account for its characteristic high proportion of zeros without introducing unnecessary complexity. The fundamental question addressed in this Application Note is whether negative binomial (NB) models provide superior fit for UMI count data compared to zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) models, particularly within the context of stem cell research where accurately identifying subtle expression differences is paramount.

The distinction between UMI counts and read counts is essential for proper model selection. While read counts from full-length scRNA-seq protocols often show characteristics requiring zero-inflated modeling, evidence increasingly suggests that UMI counts follow a different statistical distribution. Understanding this distinction helps researchers avoid model misspecification, which can lead to reduced statistical power, false positives in differential expression analysis, and inaccurate biological interpretations in stem cell differentiation studies.

Theoretical Foundation: Distribution Properties of UMI-Count Data

The Multinomial Sampling Foundation of UMI Counts

UMI-count data originates from a fundamentally different generative process than read-count data. When a cell containing ti total mRNA transcripts is processed through UMI-based scRNA-seq protocols, the resulting UMI count ni is substantially lower (ni ≪ ti) due to technical losses during capture, reverse transcription, and library preparation. The critical insight is that which molecules successfully become UMIs is essentially a random sampling process [23]. This sampling process can be effectively modeled using the multinomial distribution, which naturally accounts for the zeros observed in scRNA-seq data without requiring special zero-inflation parameters.

The multinomial model for UMI counts posits that the observed count for gene j in cell i, denoted xij, arises from sampling a fixed number of molecules (ni) across all genes according to probability parameters pij that reflect true relative expression levels. Under this model, the abundance of zeros is adequately explained by low capture efficiency and biological variation in true expression levels—no separate zero-generating mechanism is required. Empirical evidence from negative control datasets supports this theoretical foundation, demonstrating that UMI counts follow a discrete distribution with no zero inflation [23].

Comparative Analysis of Statistical Models

Table 1: Comparison of Statistical Models for scRNA-seq Data

| Model | Key Parameters | Assumed Zero Mechanism | Suitability for UMI Data | Computational Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poisson | Mean (λ) | Sampling variation | Poor (underestimates variance) | Low |

| Negative Binomial | Mean (μ), Dispersion (θ) | Sampling variation + biological noise | Excellent | Moderate |

| Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) | Mean (μ), Dispersion (θ), Zero-inflation (π) | Sampling variation + technical dropouts | Overparameterized for UMI data | High |

| Hurdle Models | Separate parameters for zero vs. non-zero | Distinct processes for zero and positive counts | Unnecessary for UMI data | High |

The negative binomial model effectively captures the mean-variance relationship observed in UMI count data through its dispersion parameter, which accounts for overdispersion beyond Poisson sampling variance. This overdispersion arises from both biological heterogeneity (e.g., stochastic expression bursts) and technical noise. Extensive model comparisons using likelihood ratio tests on real UMI datasets reveal that the ZINB model does not provide significantly better fit than the NB model for the vast majority of genes, indicating that the additional zero-inflation parameter is unnecessary [24]. In one comprehensive evaluation, exactly 0% of genes tested across multiple UMI-based protocols showed preference for ZINB over NB at a false discovery rate of 0.05 [24].

Experimental Evidence: Empirical Support for Negative Binomial Models

Systematic Model Comparisons

Several rigorous studies have directly compared the performance of negative binomial and zero-inflated models for UMI count data. In a landmark analysis, researchers examined four UMI-based scRNA-seq protocols (CEL-Seq2/C1, Drop-Seq, MARS-Seq, and SCRB-Seq) using a backward selection strategy on three nested models: Poisson, NB, and ZINB [24]. The results were striking—while read-count data from the same protocols showed 9.4–34.5% of genes preferring ZINB over NB, exactly 0% of genes measured with UMI counts preferred ZINB over NB. Furthermore, a substantial proportion of genes (39.4–84.0%) were adequately modeled by the simple Poisson distribution for UMI counts, suggesting relatively modest overdispersion [24].

These findings challenge the prevailing assumption that scRNA-seq data universally requires complex zero-inflated models. The evidence strongly indicates that UMI counting substantially simplifies the statistical properties of scRNA-seq data, making NB models sufficient for most genes. This has important implications for stem cell researchers, as NB models offer greater numerical stability and computational efficiency compared to ZINB models, which frequently encounter convergence issues during optimization [25].

Table 2: Sources of Zero Counts in scRNA-seq Experiments

| Source Type | Specific Mechanisms | Relevance to UMI Data |

|---|---|---|

| Biological | Stochastic transcription bursts, Phased gene expression, Transcript degradation | Affects all technologies |

| Technical | Inefficient reverse transcription, Low mRNA capture efficiency, Cell dissociation effects | Affects all technologies |

| Protocol-specific | PCR amplification bias (read counts), Molecular sampling (UMI counts) | Technology-dependent |

| Cell quality | Cell death, Cytoplasmic RNA leakage, Poor cell viability | Affects all technologies |

Understanding the sources of zeros in scRNA-seq data helps explain why NB models suffice for UMI counts. The "dropout" phenomenon, often cited to justify zero-inflated models, may be less relevant to UMI data than previously assumed. While UMI-based scRNA-seq can have high dropout rates, the pattern differs from read-count data. For UMI counts, zeros primarily result from a combination of low actual expression and the fundamental sampling nature of the measurement process, rather than a distinct technical failure mechanism that randomly sets counts to zero irrespective of true expression levels [26] [27].

Experimental evidence shows that even strongly expressed genes can occasionally show zeros in some cells with UMI protocols, but these zeros are consistent with NB sampling variation rather than requiring a separate zero-generating process. This distinction is crucial for stem cell researchers investigating heterogeneous populations, where accurate modeling of zero counts affects the identification of rare subpopulations and transitional states.

Practical Implementation Protocols

Differential Expression Analysis Workflow for UMI Data

Detailed Protocol for Negative Binomial-Based Differential Expression Analysis

Protocol: NBID (Negative Binomial with Independent Dispersions) Algorithm

Purpose: To accurately identify differentially expressed genes in UMI-count scRNA-seq data from stem cell populations using a negative binomial framework.

Reagents and Software Requirements:

- R statistical environment (version 4.0 or higher)

- NBID package (available from St. Jude Children's Research Hospital)

- UMI-count matrix from scRNA-seq experiment

- Cell metadata including experimental conditions

Procedure:

Input Data Preparation (Duration: 10-15 minutes)

- Format raw UMI count matrix with genes as rows and cells as columns

- Prepare sample metadata table with cell-type annotations and experimental conditions

- For stem cell studies, include relevant covariates (differentiation stage, cell cycle status)

Model Initialization (Duration: 2-5 minutes)

Parameter Estimation (Duration: 15-60 minutes, depending on dataset size)

- Estimate gene-specific dispersions using conditional maximum likelihood

- Fit negative binomial generalized linear models for each gene

- Incorporate batch effects as random effects when applicable [28]

Hypothesis Testing (Duration: 5-15 minutes)

- Perform likelihood ratio tests between experimental conditions

- Apply false discovery rate correction for multiple testing

- Filter results based on fold-change and adjusted p-value thresholds

Result Interpretation (Duration: 30+ minutes)

- Identify significantly differentially expressed genes

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis on results

- Validate key findings using independent methods

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For convergence issues, reduce the number of covariates in the model

- For unstable dispersion estimates, use trended dispersion approaches

- When analyzing rare stem cell populations, consider mixed models to account for subject-level effects [28]

Advanced Analytical Frameworks

Mixed Model Extensions for Complex Experimental Designs

Stem cell research often involves multi-subject designs where cells are collected from multiple donors or experimental replicates. In such cases, advanced negative binomial mixed models (NBMMs) account for hierarchical data structures. The NEBULA algorithm efficiently decomposes total overdispersion into subject-level and cell-level components, addressing both technical and biological sources of variation [28].

For stem cell researchers investigating disease mechanisms or treatment responses across multiple patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cell lines, NBMMs provide crucial advantages. They properly control false positive rates when testing subject-level variables (e.g., genotype, treatment condition) by accounting for the non-independence of cells from the same subject. Simulation studies demonstrate that NBMMs maintain appropriate type I error rates while achieving better power compared to models that ignore the hierarchical structure [28].

Feature Selection and Dimension Reduction for UMI Data

Based on the multinomial foundation of UMI counts, feature selection using deviance statistics outperforms traditional highly variable gene selection methods. The deviance effectively measures each gene's contribution to total heterogeneity while accounting for the mean-variance relationship of count data. Similarly, generalized principal component analysis (GLM-PCA) applied directly to raw UMI counts provides superior dimension reduction compared to PCA on log-normalized data, which can be distorted by the high proportion of zeros [23].

Table 3: Recommended Computational Tools for UMI-Count Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Model Foundation | Applicable to Stem Cell Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| NBID | Differential expression | Negative binomial | Yes - heterogeneous populations |

| NEBULA | Multi-subject analysis | Negative binomial mixed model | Yes - patient-derived lines |

| SwarnSeq | Differential expression | Zero-inflated negative binomial | Limited advantage for UMI data |

| scMMST | Batch effect correction | Mixed models | Yes - multi-batch experiments |

| TensorZINB | Large-scale analysis | ZINB with deep learning | Overparameterized for UMI data |

Application to Stem Cell Research

Case Study: Identifying Stem Cell Subpopulations

In a practical application to stem cell biology, researchers applied NB-based differential expression analysis to identify marker genes defining subpopulations in rhabdomyosarcoma cells [29]. The NBID algorithm successfully identified genes separating subpopulations with distinct expression patterns, suggesting novel mechanisms of solid tumor progression. This demonstrates the utility of NB models for uncovering biologically meaningful heterogeneity in stem cell systems.

For stem cell researchers investigating differentiation processes, NB models provide sensitive detection of expression changes in transitional states, where cell-to-cell heterogeneity is high but zero-inflation is minimal in UMI data. The numerical stability of NB estimation ensures reliable results even for genes with moderate to low expression, which often include key regulators of stem cell fate decisions.

Recommendations for Experimental Design

Based on the statistical properties of UMI-count data, we recommend:

- Protocol Selection: Prioritize UMI-based scRNA-seq protocols over read-count methods for quantitative expression analysis

- Sample Size Considerations: Include sufficient biological replicates (subjects/stem cell lines) rather than maximizing cell numbers per subject

- Sequencing Depth: Aim for 20,000-50,000 UMIs per cell to adequately capture mid-to-low abundance transcripts

- Quality Control: Monitor technical metrics but recognize that zeros are expected biological features rather than necessarily indicating failed measurements

The statistical foundations and empirical evidence consistently demonstrate that negative binomial models provide superior fit for UMI-count scRNA-seq data compared to zero-inflated alternatives in most stem cell research contexts. The multinomial sampling process underlying UMI counting naturally produces zeros consistent with NB distributions without requiring additional zero-inflation parameters. By adopting appropriately parameterized NB models, stem cell researchers can achieve more numerically stable, computationally efficient, and biologically accurate analysis of single-cell transcriptomes, ultimately advancing our understanding of stem cell biology and its therapeutic applications.

From Theory to Bench: Implementing UMI scRNA-seq to Decipher Stem Cell Fate and Function

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the dissection of cellular heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution. For stem cell studies, where cellular plasticity and diverse differentiation trajectories are fundamental, scRNA-seq provides unparalleled insights into molecular networks and cellular states [14]. The incorporation of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) has been particularly transformative for quantitative scRNA-seq, as they mitigate amplification bias and enable precise molecular counting of transcripts [13] [30]. This technical advance is crucial for accurately capturing the subtle expression differences that define stem cell heterogeneity, identify rare subpopulations, and trace developmental lineages.

The journey from a complex biological sample to a sequencing library ready for interpretation is a multistep process where each stage critically influences the final data quality. This application note provides a comprehensive experimental workflow breakdown, detailing best practices from single-cell isolation through cDNA synthesis and library preparation, with particular emphasis on their application within stem cell research utilizing UMI barcoding for quantitative analysis.

Single-Cell Isolation: The Foundation of scRNA-seq

Isolation Strategies and Their Applications

The initial step of single-cell isolation is arguably the most critical, as it determines the representativeness and viability of the input material. The choice of method involves trade-offs between throughput, viability, and compatibility with downstream applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Single-Cell Isolation Methods for scRNA-seq

| Method | Throughput | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Ideal for Stem Cell Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet-Based (e.g., 10x Genomics) | High (Thousands to millions of cells) | Microfluidics to encapsulate single cells in oil droplets [31] | High throughput, commercial scalability, early barcoding | Limited capture efficiency (2-50%), specialized equipment required, higher multiplet rates [14] | Profiling large, heterogeneous populations (e.g., organoids) |

| Plate-Based (e.g., SMART-Seq) | Low to Medium (96-384 wells) | FACS or manual deposition of single cells into multi-well plates [32] | High sensitivity, full-length transcript coverage, flexible input | Lower throughput, higher reagent costs, requires pre-amplification [14] | Deep characterization of predefined stem cell subsets |

| Combinatorial Barcoding (e.g., Parse Biosciences) | Very High (Thousands to millions of cells) | Cells act as reaction chambers; barcodes are added over multiple rounds of splitting and pooling [31] | Scalability, does not require specialized equipment, low multiplet rates [31] | Protocol complexity, longer hands-on time, compatible with fixed cells | Large-scale perturbation screens or time-course experiments |

| Laser Capture Microdissection | Low | Direct microscopic visualization and isolation of cells from tissue context [14] | Preserves spatial context, precise selection | Very low throughput, technically challenging, potential RNA degradation | Studying stem cells in their anatomical niche (e.g., intestinal crypts) |

Practical Considerations for Stem Cell Samples

Successful isolation of stem cells requires careful handling to preserve viability and minimize transcriptional stress. For solid tissues, enzymatic digestion must be optimized to dissociate the extracellular matrix without damaging cell surface markers critical for stem cell identity.

- Enzyme Selection: A blend of collagenase (targets collagen), dispase (targets fibronectin and collagen IV), and hyaluronidase (targets hyaluronan) is often effective for breaking down the extracellular matrix [33]. For sensitive epitopes, trypsin alternatives like Accutase or TrypLE are recommended as they are less aggressive on cell surface proteins [33].

- Viability Preservation: The dissociation process can activate stress responses, including the induction of immediate early genes, which can confound transcriptomic analysis [14]. This is particularly relevant for neural stem cells. Rapid processing and maintaining samples on ice can mitigate this. Using nuclei instead of intact cells (single-nucleus RNA-seq) is a valuable alternative for particularly sensitive cell types or frozen samples [14] [34].

- Quality Control: The resulting cell suspension must be assessed for viability (typically >80% via trypan blue or propidium iodide exclusion), concentration, and single-cell efficiency. Cell clumps (doublets or multiplets) must be minimized as they can be misidentified as novel cell types during analysis [31]. Adding DNase I during preparation can reduce stickiness caused by genomic DNA release [31].

Cell Lysis and RNA Capture: Preserving Molecular Integrity

Once single cells are isolated, they are lysed to release RNA. Lysis must be immediate and thorough to inhibit RNases and maximize RNA recovery. Common lysis buffers contain guanidine thiocyanate (a potent denaturant) and RNase inhibitors [32]. Following lysis, mRNA is captured using oligo(dT) primers that hybridize to the poly-A tail of mature mRNAs. This step enriches for messenger RNA and depletes ribosomal RNA. In UMI-based protocols, the capture oligonucleotides are conjugated with cell barcodes (to label all transcripts from a single cell) and UMIs (to label individual mRNA molecules) [13] [35]. These barcodes are essential for the quantitative nature of the protocol, as they allow bioinformatic demultiplexing of cells and correction for amplification bias.

cDNA Synthesis: Converting RNA to a Stable Amplifiable Library

Reverse Transcription and Template Switching

The minute quantity of RNA from a single cell (∼10–50 pg) must be converted to a more stable and amplifiable complementary DNA (cDNA) library. This is achieved through reverse transcription (RT), primed by the barcoded oligo(dT) primers. The reverse transcriptase enzyme copies the RNA template into first-strand cDNA. Many advanced protocols (e.g., SMART-Seq) employ reverse transcriptases with terminal transferase activity. Upon reaching the 5' end of the mRNA, this enzyme adds a few non-templated nucleotides (typically deoxycytosines), creating an overhang [32]. A specially designed "template-switch" oligonucleotide (TSO) with riboguanosines at its 3' end then base-pairs with this overhang, allowing the reverse transcriptase to continue replication, effectively adding a universal primer sequence to the 5' end of the cDNA [32]. This mechanism ensures that full-length transcripts are captured with common adapter sequences on both ends, which is crucial for efficient downstream amplification and library construction.

Optimizing Reverse Transcription

The choice of reverse transcriptase significantly impacts cDNA yield, length, and representation, especially for challenging RNA with secondary structures.

Table 2: Reverse Transcriptase Attributes for cDNA Synthesis

| Attribute | AMV Reverse Transcriptase | MMLV Reverse Transcriptase | Engineered MMLV (e.g., SuperScript IV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNase H Activity | High | Medium | Low/None [36] |

| Reaction Temperature | Up to 42°C | Up to 37°C | Up to 55°C [36] |

| Typical Reaction Time | 60 minutes | 60 minutes | 10 minutes [36] |

| Optimal Target Length | ≤5 kb | ≤7 kb | Up to 14 kb [36] |

| Relative Yield with Suboptimal RNA | Medium | Low | High [36] |

For stem cell applications, where transcripts of key regulatory genes can be long and complex, using an engineered MMLV reverse transcriptase (RNase H–, thermostable) is advantageous. The higher reaction temperature (50–55°C) helps denature GC-rich regions and secondary structures, leading to increased yield, better representation of complex transcripts, and higher sensitivity [36].

cDNA Amplification and Library Preparation for Sequencing

The synthesized cDNA is amplified by PCR using primers targeting the universal sequences added during reverse transcription and template switching [32]. Following amplification, the cDNA is converted into a sequencing-ready library. The Nextera XT system (Illumina), which uses a Tn5 transposase for simultaneous fragmentation and adapter tagging ("tagmentation"), is a common and efficient method [32]. This step appends sequencing adapters, including sample-specific indices (i.e., i7 and i5 indexes), enabling multiplexing of multiple libraries in a single sequencing run. Final library quality is assessed using fragment analyzers or bioanalyzers to confirm a distribution of fragment sizes, typically between 300–400 bp to 9–10 kb for pre-amplified cDNA, and a sharper peak around 400–500 bp for the final sequencing library [31] [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Workflows

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Collagenase/Dispase Blend | Enzymatic digestion of extracellular matrix components (collagen, fibronectin) [33] | Critical for liberating stem cells from solid tissues; concentration and time must be optimized to maintain viability. |

| DNase I | Degrades free DNA released by dying cells [33] | Reduces cell clumping and stickiness in suspension, lowering multiplet rates [31]. |

| Agencourt RNAClean XP SPRI Beads | Solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) for RNA and cDNA cleanup and size selection [32] | Used for purifying RNA after lysis and cDNA after amplification; removes enzymes, salts, and short fragments. |

| SMARTer Ultra Low Input RNA Kit | All-in-one system for reverse transcription and cDNA amplification via template-switching [32] | Ideal for plate-based protocols; ensures high sensitivity for low-input RNA. |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | Prepares sequencing libraries via tagmentation [32] | Enables fast, efficient, and multiplexed library construction from amplified cDNA. |

| 10x Genomics Chromium Single Cell Gene Expression Kits | Integrated reagent kit for droplet-based scRNA-seq [14] | Provides a complete, commercialized workflow from cells to libraries, including all barcodes and enzymes. |

| InvITrogen ezDNase Enzyme | Thermolabile, double-strand-specific DNase for gDNA removal [36] | Efficiently removes contaminating genomic DNA from RNA samples without requiring a separate inactivation step that can damage RNA. |

The following diagram summarizes the complete experimental workflow for UMI-based scRNA-seq, from sample preparation to sequencing.

A rigorous and optimized wet-lab workflow is the foundation for any successful scRNA-seq study. For stem cell research, where questions often revolve around subtle transitions and rare cell states, the quantitative accuracy afforded by UMI barcoding is indispensable. By carefully executing each step—from gentle cell isolation to efficient cDNA synthesis and library preparation—researchers can generate high-quality data that truly reflects the underlying biology. This detailed protocol provides a roadmap for leveraging scRNA-seq to unlock the dynamic transcriptional landscapes of stem cells, fueling discoveries in development, disease, and regenerative medicine.

For stem cell researchers, selecting the appropriate single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) platform is crucial for accurately capturing cellular heterogeneity and dynamic transitions. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of three major technology approaches to guide your experimental design.

| Feature | 10x Genomics (3' v3.1) | Parse Biosciences (Evercode) | Traditional Plate-Based (e.g., CEL-Seq2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Technology | Droplet-based microfluidics [37] [38] | Split-pool combinatorial barcoding (SPLiT-seq) [37] [31] [39] | Multi-well plate-based isolation |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited per run; requires cell hashing [39] | High (up to 96-384 samples in a single run) [37] [39] | Inherently low; limited by plate well number |

| Cell Throughput | High (80K-960K cells per kit) [38] | Very High (up to 1 million cells per experiment) [37] [39] | Low (typically hundreds to thousands of cells) |

| Cell Recovery/Capture Efficiency | ~53-56.5% [37] [39] | ~27-54.4% [37] [39] | Highly variable; can be high with careful handling |

| Genes Detected per Cell | ~1,900-2,000 (median) [37] | ~2,300-2,800 (median); nearly twice in some studies [37] [39] | Variable; often lower sensitivity |

| Key Strength | Standardized protocol, low technical variability [39] | High multiplexing, superior gene detection, no custom equipment [37] [39] | Low equipment cost, well-established protocols |

| Key Limitation | Lower gene detection sensitivity, higher multiplet rates [37] [31] | Lower cell capture efficiency, higher inter-sample variability [37] [39] | Low throughput, high hands-on time, limited scalability |

| Ideal for Stem Cell Applications | Profiling large, complex populations (e.g., organoids); immune profiling in differentiation [38] | Large-scale longitudinal studies, rare cell type identification, piloting sequencing depth [37] [31] | Small-scale, targeted studies with limited cell numbers |

Performance Analysis for Stem Cell Research

Sensitivity and Accuracy in Gene Detection

Quantitative data from benchmark studies is essential for evaluating a platform's ability to resolve subtle transcriptional differences, a key requirement in stem cell biology.

Table 2: Performance Metrics from Benchmarking Studies

| Metric | 10x Genomics | Parse Biosciences | Notes & Implications for Stem Cell Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Genes per Cell | 1,884 - 1,984 [37] | 2,283 - 2,319 [37] | Parse's higher sensitivity is critical for identifying rare cell states, lowly expressed transcription factors, and subtle heterogeneity within stem cell populations. |

| Cell Capture Efficiency | 53% - 56.5% [37] [39] | 27% - 54.4% [37] [39] | 10x offers more predictable cell recovery, advantageous for precious or low-input stem cell samples. Parse's efficiency is sample-dependent [39]. |

| Multiplet Rate | Low double-digit percentage [31] | Low single-digit percentage [31] | Parse's lower multiplet rate reduces data artifacts, providing a more accurate picture of cell identities, which is vital for lineage tracing. |

| Technical Variability | Lower; high reproducibility between replicates [39] | Higher inter-sample variability observed [39] | 10x provides more precise data, beneficial for quantifying expression changes during differentiation or in response to perturbations. |

| Transcriptome Coverage | 3'-biased [37] | Whole-transcriptome (via oligo-dT + random hexamers) [37] | Parse's method reduces 3' bias, offering a more uniform view of the transcriptome, which can be valuable for isoform-level analyses. |

Technical and Practical Considerations

Library Efficiency and Sequencing: 10x Genomics demonstrates a higher fraction of valid reads (~98% vs. ~85% for Parse), meaning less sequencing capacity is wasted on background noise [37]. Parse's unique sub-library structure allows researchers to pilot sequencing depth with one sub-library to determine the optimal saturation point for cost-effective sequencing of the entire experiment [31].

Compatibility with Complex Samples: Stem cell-derived samples can be challenging. Droplet-based methods like 10x are sensitive to ambient RNA released from dying cells, which can lead to misattribution of transcripts [31] [39]. Parse's wash steps during the split-pool process reduce this issue, making it potentially more robust for samples with varying viability [31]. For fixed samples, 10x Genomics' Flex assay is specifically designed to preserve biology and is compatible with FFPE tissues and fixed whole blood [38].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

10x Genomics Chromium (3' Gene Expression)

The 10x workflow is designed for high-throughput cell partitioning and barcoding via proprietary microfluidics chips [38].

Key Protocol Steps:

- Sample Preparation: Create a high-viability (>90%) single-cell suspension in PBS with 0.04% BSA, targeting 1,000-1,600 cells/μL [40].

- GEM Generation: On a Chromium chip, single cells, barcoded Gel Beads, and RT reagents are co-partitioned into nanoliter-scale Gel Beads-in-emulsion (GEMs). Cell lysis and reverse transcription occur within each GEM, labeling all cDNA from a single cell with the same cellular barcode and each mRNA molecule with a unique UMI [38].

- Library Prep: GEMs are broken, and cDNA is purified and amplified. Following fragmentation, end-repair, and adapter ligation, libraries are enriched for final sequencing-ready products [40] [38].

Parse Biosciences Evercode (SPLiT-seq)

This protocol uses the cell itself as a reaction vessel through fixation and permeabilization, eliminating the need for specialized partitioning equipment [31].

Key Protocol Steps:

- Cell Fixation: Cells are fixed and permeabilized, stabilizing the transcriptome and allowing for workflow flexibility [31] [39].

- Combinatorial Barcoding: Fixed cells are distributed to a 96-well plate for the first round of in-situ reverse transcription, where well-specific barcodes are added. Cells are then pooled, split into a new plate, and a second barcode is added. This split-pool process is repeated, typically four times, to assign each cell a unique combination of barcodes [37] [31].

- Library Preparation: Cells are pooled and lysed. cDNA is fragmented, and a final barcode is added via adapter ligation to create sublibraries, which are then amplified and ready for sequencing [31].

Plate-Based Methods (CEL-Seq2)

As a representative plate-based method, CEL-Seq2 provides a reference for lower-throughput, more accessible approaches.

Key Protocol Steps:

- Cell Sorting: Single cells are manually or robotically sorted into individual wells of a 96- or 384-well plate containing lysis buffer.

- In-Well Reverse Transcription: mRNA from each cell is reverse-transcribed, and the second strand is synthesized with a template-switching oligonucleotide (TSO) to incorporate universal priming sites.

- Pooling and Amplification: cDNA from all wells is pooled and then amplified by in vitro transcription (IVT), a hallmark of CEL-Seq2. The resulting amplified RNA is fragmented and converted into a sequencing library.

The following diagram illustrates the core technological and workflow differences between these three major platforms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines key materials and reagents required for implementing these scRNA-seq protocols in a stem cell research setting.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Description | Platform Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Viability Stain (e.g., DAPI, Propidium Iodide) | Distinguishes live/dead cells for assessing suspension quality and FACS sorting. | Universal - Critical for all platforms to ensure high-quality input [40]. |

| Dissociation Enzymes (e.g., Collagenase, Trypsin) | Breaks down extracellular matrix to create single-cell suspensions from tissues or organoids. | Universal - Required for sample preparation [41]. |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA integrity during dissociation and library preparation. | Universal - Essential for preserving transcriptome fidelity [40]. |

| Barcoded Gel Beads | Microparticles containing cell barcode and UMI oligonucleotides for transcript capture. | 10x Genomics - Core consumable for droplet-based partitioning [38]. |

| Fixation/Permeabilization Kit | Reagents to cross-link and permeabilize cells for in-situ barcoding. | Parse Biosciences - Enables the SPLiT-seq workflow [39]. |

| Evercode Barcoded Plates | Pre-plated oligonucleotides for combinatorial barcoding rounds. | Parse Biosciences - Core consumable for the split-pool process. |

| Template Switching Oligo (TSO) | Enables template switching during RT for full-length cDNA synthesis. | Plate-Based (CEL-Seq2) & 10x (5' kit) - Key component of the reaction [38]. |

| SPRIselect Beads | Magnetic beads for size selection and cleanup of cDNA and final libraries. | Universal - Used in purification steps across all protocols [31]. |

| Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) | Sample-specific barcodes for multiplexing libraries during sequencing. | Universal - Allows pooling of multiple libraries on one sequencing run [40]. |

The choice between 10x Genomics, Parse Biosciences, and plate-based methods hinges on the specific goals and constraints of the stem cell research project.

Choose 10x Genomics when your study requires high cell throughput from a limited number of samples, demands high technical reproducibility with low variability, and leverages standardized, widely supported protocols. It is ideal for large-scale atlases of organoids or differentiating cultures [39] [38].

Choose Parse Biosciences for large-scale studies involving many samples or conditions, such as detailed time-course experiments of stem cell differentiation or drug screens. Its superior gene detection sensitivity is paramount for identifying rare stem cell subtypes or transient progenitor states, and its scalability offers a lower cost per cell in highly multiplexed designs [37] [39].

Consider Plate-Based Methods like CEL-Seq2 primarily for pilot studies with very limited cell numbers, or in laboratories where equipment budgets are constrained and the research questions can be answered with lower-throughput, targeted profiling.

Ultimately, the integration of UMI barcoding across these platforms provides the quantitative accuracy needed to resolve the dynamic transcriptional landscape of stem cells, from pluripotency through lineage commitment.