Unraveling the Mechanisms of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Immunomodulation: From Basic Science to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-mediated immunomodulation, a rapidly advancing field with significant therapeutic potential.

Unraveling the Mechanisms of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Immunomodulation: From Basic Science to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-mediated immunomodulation, a rapidly advancing field with significant therapeutic potential. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational biology of MSC interactions with innate and adaptive immune systems, examine current methodological approaches and clinical applications in diseases like GvHD and allergic rhinitis, address key challenges in standardization and safety, and evaluate validation strategies through preclinical and clinical trials. The synthesis of these four core intents offers a roadmap for advancing MSC-based therapies from bench to bedside, highlighting emerging technologies such as engineered MSCs and exosome-based treatments that promise to enhance efficacy and safety in regenerative medicine and immunotherapy.

The Immunomodulatory Arsenal of MSCs: Decoding Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) have emerged as one of the most promising tools in cell and gene therapy, attracting considerable attention for their applications in regenerative medicine and immunomodulation [1]. However, the field has been challenged by significant heterogeneity in how these cells are defined, characterized, and reported across studies. Recognizing this critical issue, the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) established minimal criteria to standardize the definition of MSCs, aiming to enhance rigor, reproducibility, and transparency in both preclinical and clinical research [2]. These criteria serve as an essential foundation for research into MSC immunomodulation, ensuring that scientists worldwide are investigating comparable cell populations. Despite these efforts, a 2022 scoping review revealed that only 18% of published articles explicitly referred to the ISCT minimal criteria, and only 20% reported at least one functional assay [2]. This highlights the ongoing need to reinforce these standards, particularly as researchers delve deeper into the sophisticated immunomodulatory mechanisms that make MSCs biologically and therapeutically compelling.

The ISCT Minimal Defining Criteria for MSCs

The ISCT criteria, established in 2006, provide a three-part framework for defining MSCs, which distinguishes them from other cell types in the stromal compartment [3] [4].

Plastic Adherence

The primary and most fundamental criterion is that MSCs must be plastic-adherent when maintained under standard culture conditions [3] [5]. This is a functional characteristic observed during in vitro culture, where MSCs selectively attach to the surface of plastic tissue culture vessels, while hematopoietic and other non-MSC populations remain in suspension and can be removed during medium changes.

Surface Antigen Expression

MSCs must demonstrate a specific immunophenotype, characterized by the positive expression of a set of surface markers and the absence of hematopoietic markers. The expression must be ≥95% positive for positive markers and ≤2% positive for negative markers [5].

Table 1: Required Surface Marker Profile for MSCs as per ISCT Criteria

| Marker Category | Marker Examples | Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Expression | CD73, CD90, CD105 | ≥95% Positive |

| Negative Expression | CD11b, CD14, CD19, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR | ≤2% Positive |

It is important to note that beyond this core set, the panel of MSC-associated markers has expanded. Researchers often simultaneously verify additional markers such as CD29, CD44, CD146, CD166, and STRO-1 to increase confidence in cell identification, though their expression can vary depending on the tissue of origin [3]. For instance, STRO-1 is positively expressed in bone marrow and dental tissue MSCs but is negative in adipose-derived MSCs [5].

Tri-Lineage Differentiation Potential

A central defining feature of MSCs is their multipotency—the ability to differentiate into multiple cell types of the mesodermal lineage. The ISCT requires that MSCs must be able to differentiate in vitro into osteoblasts (bone), adipocytes (fat), and chondroblasts (cartilage) [3] [4]. Confirmation of this tri-lineage differentiation provides the most functional evidence for verifying MSC identity beyond surface markers.

MSCs can be isolated from a wide variety of adult and perinatal tissues. While all sources yield cells that fulfill the core ISCT criteria, significant biological differences exist in their proliferation capacity, gene expression profiles, secretory signatures, and immunomodulatory potency [4] [6]. These differences are critical to consider when selecting a cell source for specific immunomodulation research or therapy development.

Table 2: Characteristics of MSCs from Different Tissue Sources

| Tissue Source | Key Advantages | Reported Functional Differences & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow (BM-MSCs) | Considered the "gold standard"; most advanced in clinical trials [4]. | Produce more VEGF and SDF-1, potentially making them more suitable for supporting angiogenesis and homing to bone marrow [4]. |

| Adipose Tissue (AT-MSCs) | Less invasive and painful collection; cells can longer retain stem cell phenotype [1]. | Some studies report more potent immunomodulatory effects than BM-MSCs [7] [6]. |

| Wharton's Jelly (WJ-MSCs) | Fetal source with high proliferation capacity; minimal risk of initiating an allogeneic immune response [7] [6]. | Higher proliferation capacity and longer telomeres than adult sources [4] [6]. WJ-MSC-CM shows a strong regenerative profile, promoting wound healing and VEGF expression in SSc fibroblasts [1]. |

| Umbilical Cord Blood (CB-MSCs) | Fetal source; ease of collection [7]. | Lower recovery rate in culture; slower to start expanding; may express less CD90 and CD105 compared to BM-/AT-MSCs [4]. |

| Placenta (PL-MSCs) | Fetal source; high proliferation capacity [4]. | Express genes for hematopoietic growth factors (LIF, SCF, TPO) and can support ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic stem cells [4]. |

The selection of a tissue source is not merely a logistical decision but a critical experimental variable. For example, a 2025 study directly comparing the secretome and functional effects of MSCs from four different sources found that WJ-MSC-conditioned medium and BM-MSC-conditioned medium showed a greater regenerative profile than those from cord blood or adipose tissue in models of skin therapy for Systemic Sclerosis. Notably, WJ-MSC-CM significantly promoted fibroblast-mediated wound healing processes and VEGF expression in SSc fibroblasts, even compared to BM-MSC-CM [1]. This underscores how the tissue source can directly influence the therapeutic mechanism of action, which is a vital consideration for immunomodulation research.

Experimental Protocols for Verifying MSC Identity

Rigorous quality control and characterization are paramount. The following methodologies are essential for confirming that a cell population meets the ISCT criteria and is suitable for research into immunomodulation.

Flow Cytometry for Surface Marker Expression

Purpose: To quantitatively assess the presence of positive and negative surface markers as defined by the ISCT. Detailed Protocol:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest MSCs at the appropriate passage (typically P2-P4) using a standard dissociation reagent like trypsin-EDTA. Wash cells with a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution containing 1-5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) to block non-specific binding.

- Antibody Staining: Resuspend approximately 1x10^5 to 5x10^5 cells per tube in staining buffer. Incubate with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, CD14/CD11b, CD19/CD79α, and HLA-DR for 30-60 minutes on ice or at 4°C in the dark. Include appropriate isotype controls for each antibody to set fluorescence baselines.

- Analysis: Wash cells to remove unbound antibody and resuspend in staining buffer. Analyze the cells using a flow cytometer. A population is considered positive for a marker if ≥95% of cells express CD73, CD90, and CD105, and ≤2% express the hematopoietic markers [3] [5]. Multicolour flow cytometry is recommended to examine several markers simultaneously on the same cell population.

Colony-Forming Unit (CFU) Assay

Purpose: To evaluate the clonogenic and self-renewal capacity of MSCs. Detailed Protocol:

- Cell Seeding: Create a single-cell suspension of MSCs and perform serial dilution. Seed the cells at a clonogenic density of 10-100 cells per cm² in a tissue culture dish or plate. Using a low density is critical to ensure that colonies form from single cells.

- Culture: Culture the cells in standard growth medium (e.g., α-MEM or DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS) for 8-14 days, replacing the medium every 3-4 days.

- Staining and Quantification: After colonies become visible to the eye, carefully aspirate the medium, wash with PBS, and fix the cells with 4% formaldehyde or methanol. Stain with Giemsa or crystal violet for 20-30 minutes. Rinse gently with water, air dry, and count the number of colonies. A colony is typically defined as a cluster of >50 cells [3].

Tri-Lineage Differentiation Assays

Purpose: To functionally confirm the multipotent differentiation potential of MSCs into osteocytes, adipocytes, and chondrocytes. Detailed Protocol:

- Osteogenic Differentiation:

- Induction: Seed MSCs at a high density (~3x10^4 cells/cm²). Once they reach 70% confluence, replace the standard growth medium with osteogenic induction medium. This medium is typically composed of base medium supplemented with 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50-100 µM ascorbate-2-phosphate, and 10-100 nM dexamethasone.

- Culture and Analysis: Culture the cells for 2-4 weeks, changing the induction medium twice weekly. To confirm differentiation, fix the cells and stain with Alizarin Red S to detect calcium deposits in the mineralized extracellular matrix [3]. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity can also be measured as an early marker of osteogenesis.

Adipogenic Differentiation:

- Induction: Seed MSCs at a high density (~2x10^4 cells/cm²). At 100% confluence, initiate differentiation by replacing the growth medium with adipogenic induction medium. A common cocktail includes base medium with 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), 1 µM dexamethasone, 10 µM insulin, and 200 µM indomethacin.

- Culture and Analysis: Culture the cells for 1-3 weeks. The induction medium can be alternated with a maintenance medium (containing only insulin) every 2-3 days. To confirm adipogenesis, fix the cells and stain with Oil Red O to visualize the accumulated intracellular lipid droplets [3].

Chondrogenic Differentiation:

- Pellet Culture: Centrifuge 2.5x10^5 MSCs in a conical polypropylene tube to form a micromass pellet. Culture the pellet in chondrogenic induction medium, which often contains high-glucose DMEM, 1% ITS (Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium), 100 nM dexamethasone, 50 µM ascorbate-2-phosphate, and 10 ng/mL TGF-β3 (a key chondrogenic factor).

- Culture and Analysis: Culture the pellets for 3-4 weeks, changing the medium every 2-3 days. To confirm chondrogenesis, fix the pellets, embed in paraffin, section, and stain with Alcian Blue to detect the presence of sulfated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in the cartilage-specific extracellular matrix [3].

MSC Immunomodulation: Mechanisms and Research Workflows

The immunomodulatory capacity of MSCs is not constitutive but is primed by inflammatory factors in the microenvironment, particularly IFN-γ, often in combination with TNF-α, IL-1α, or IL-1β [8]. This licensing process triggers MSCs to employ a dual-mechanism strategy involving cell-to-cell contact and paracrine activity to suppress immune responses.

Key Immunomodulatory Mechanisms

- Cell-to-Cell Contact: MSCs directly interact with immune cells via surface molecules. The upregulation of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 is critical for T-cell activation and recruitment [7] [6]. MSCs also express PD-L1 and PD-L2, which can inhibit T-cell proliferation by arresting the cell cycle [7]. Furthermore, galectin-1 expression on MSCs is essential for their immunomodulatory function, and its knockdown leads to a restoration of T-cell proliferation [6].

- Paracrine Activity (Soluble Factors): The licensed MSC secretome contains a plethora of immunomodulatory factors. Key among them are:

- Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO): Catalyzes the conversion of tryptophan to kynurenine, depleting local tryptophan and inhibiting T-cell proliferation [8] [5].

- Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2): Suppresses the proliferation and function of various immune cells, including T cells and macrophages, and can switch macrophages from a pro-inflammatory M1 to an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype [7] [8].

- Transforming Growth Factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF): Contribute to the suppression of T-cell proliferation and the induction of regulatory T cells (Tregs) [8].

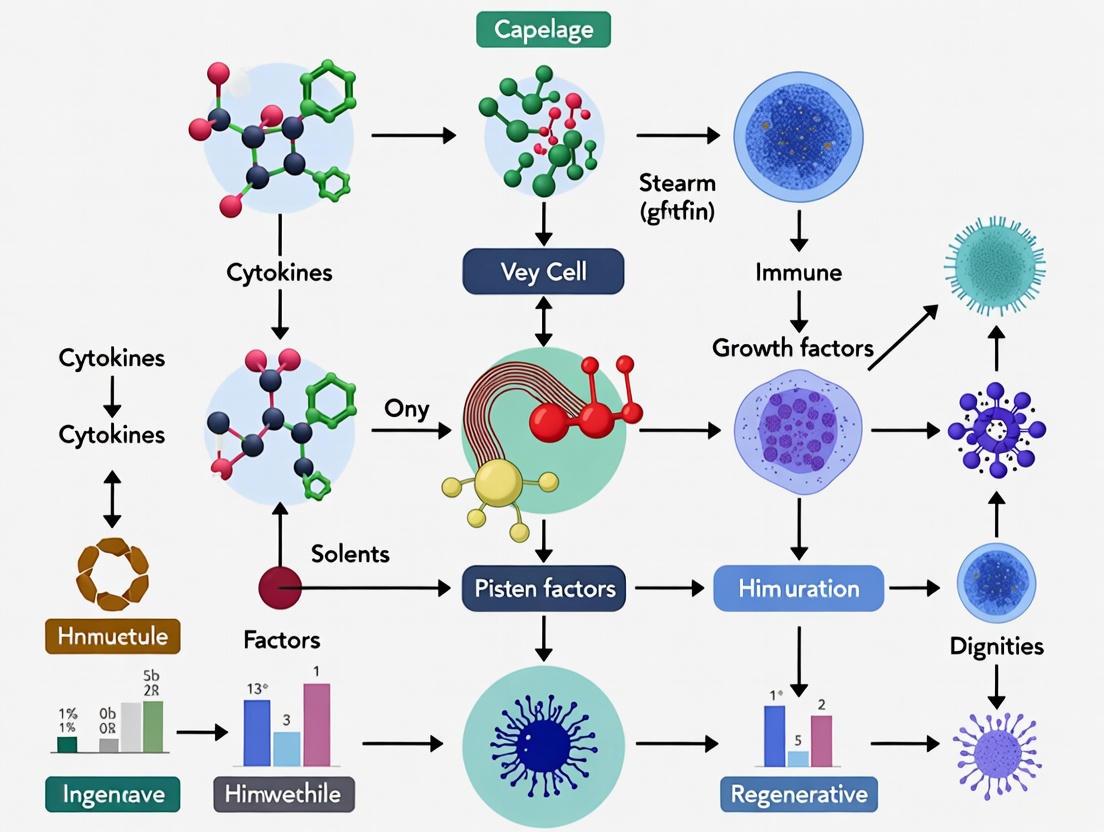

The following diagram illustrates the core immunomodulatory mechanisms and the experimental workflow for investigating them.

Diagram: MSC Immunomodulation Mechanisms & Research Workflow. The diagram illustrates how inflammatory cytokines prime MSCs, which then exert immunomodulation via cell-contact and paracrine mechanisms, leading to functional changes in immune cells. Key experimental assays for investigating these pathways are also shown.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for MSC Immunomodulation Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MSC Immunomodulation Studies

| Reagent / Assay | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Essential for verifying MSC identity (CD73, CD90, CD105) and assessing purity by excluding hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45). Also used to analyze immune cell populations (e.g., T-cells, B-cells) in co-cultures [3]. |

| Tri-lineage Differentiation Kits | Commercial kits provide optimized media and reagents to reliably demonstrate MSC multipotency (osteogenic, adipogenic, chondrogenic) as per ISCT criteria [3]. |

| Inflammatory Cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α) | Used to "license" or prime MSCs in vitro to activate their immunomodulatory functions before use in functional assays or therapeutic applications [8]. |

| Lymphocyte Proliferation Assay | Measures the ability of MSCs to suppress the proliferation of activated T-cells (e.g., using mitogens like PHA or anti-CD3/CD28 beads). A cornerstone potency assay for immunomodulation [3] [8]. |

| ELISA / Multiplex Cytokine Arrays | Quantifies the secretion of immunomodulatory factors (e.g., IDO, PGE2, TGF-β) by MSCs and measures changes in the inflammatory cytokine milieu in co-culture supernatants [1] [3]. |

| Transwell Migration Assay | Assesses the migratory and homing potential of MSCs in response to chemokines or stimuli from injured or inflamed tissues [3]. |

A rigorous adherence to the ISCT criteria is the bedrock of credible MSC research, enabling the validation of cell identity and facilitating meaningful comparisons across studies. As the field progresses, it is evident that the tissue source is a major determinant of functional potency, influencing the secretory profile and immunomodulatory mechanisms of MSCs. Future research must not only consistently apply these standards but also move towards developing more sophisticated potency assays that directly reflect the intended clinical mechanism of action. By integrating strict characterization with a nuanced understanding of source-specific biology, researchers can fully harness the potential of MSCs to develop novel and effective immunomodulatory therapies.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have emerged as one of the most promising tools in allogeneic cell therapy due to their profound immunomodulatory capabilities [9]. These multipotent cells exert their therapeutic effects through a dual-mechanism paradigm: direct cell-cell contact and secretion of soluble factors [7]. This sophisticated dual approach enables MSCs to interact with a wide spectrum of immune cells, including T cells, B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, monocytes, and dendritic cells, thereby modulating both innate and adaptive immunity [7]. The immunomodulatory functions of MSCs are not static but are dynamically influenced by the local tissue microenvironment, which dictates the balance and predominance of each mechanism [10]. Understanding this complex interplay is crucial for harnessing the full therapeutic potential of MSCs in treating inflammatory diseases, autoimmune disorders, and preventing transplant rejection [9] [11].

Cell-Cell Contact Mediated Immunomodulation

Direct cellular contact represents a fundamental mechanism through which MSCs communicate with and regulate immune cells. This contact-dependent signaling occurs through specialized surface molecules that facilitate precise cellular interactions.

Key Contact Molecules and Pathways

- Adhesion Molecules (ICAM-1 and VCAM-1): The upregulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) on MSCs is critical for initial tethering to immune cells and subsequent suppression of T-cell activation [7]. These molecules enable the formation of the immunological synapse between MSCs and T lymphocytes, facilitating downstream signaling events.

- Immunoregulatory Ligands (PD-L1/PD-L2 and Galectin-1): Human placenta-derived MSCs (PMSCs) express high levels of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and PD-L2, which inhibit T-cell proliferation by inducing cell cycle arrest [7]. Similarly, Galectin-1, abundantly expressed on MSCs, plays a pivotal role in modulating T-cell responses, as its knockdown results in restored CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation [7].

- Notch Signaling Pathway: The interaction between Notch receptors on T cells and their ligands on MSCs activates the Notch1/forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) pathway, increasing the percentage of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) [7]. This pathway represents a direct contact-mediated mechanism for expanding immunoregulatory cell populations.

The following diagram illustrates the major contact-dependent pathways MSCs use to modulate immune cell activity:

Functional Outcomes of Cellular Contact

The functional consequences of direct MSC-immune cell contact are profound. In vivo studies using syngeneic mouse models have demonstrated that contact-mediated interactions are essential for the anti-tumor effects of compact bone-derived MSCs (CB-MSCs), which involve activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells while simultaneously inhibiting Tregs in the tumor microenvironment [7]. Furthermore, research has confirmed that MSCs primed by activated T cells derived from IFN-γ −/− mice exhibit a dramatically reduced ability to suppress T-cell proliferation, underscoring the non-redundant role of cell-contact mechanisms [7]. Beyond T-cells, MSCs also regulate B-cell function through contact-dependent mechanisms. Adipose-derived MSCs (A-MSCs) have been shown to increase the survival of quiescent B-cells and facilitate their differentiation independently of T-cell help [7]. These interactions are mediated through specific signaling pathways, including p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), which leads to cell cycle arrest of B-lymphocytes in the G0/G1 phase [7].

Soluble Factor Mediated Immunomodulation

The paracrine activity of MSCs represents the second pillar of their immunomodulatory arsenal, mediated through a diverse repertoire of secreted molecules.

Major Soluble Mediators and Their Mechanisms

- Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase (IDO): This enzyme catalyzes the degradation of the essential amino acid tryptophan into kynurenine, creating a tryptophan-deficient microenvironment that suppresses T-cell proliferation and induces Treg differentiation, thereby promoting kidney allograft tolerance [7].

- Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2): MSC-secreted PGE2 plays a multifaceted role by inhibiting the differentiation of T helper 17 (Th17) cells while simultaneously promoting the switch of activated M1-like inflammatory macrophages to an M2-like anti-inflammatory phenotype [7] [11].

- Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β): This potent immunoregulatory cytokine works in concert with interleukin-10 (IL-10) to inhibit T-cell activation and cytokine production through the activation of downstream Smad and STAT3 signaling pathways [11].

- Extracellular Vesicles (EVs): MSC-derived exosomes and microvesicles serve as critical vehicles for intercellular communication, transferring bioactive molecules like miRNAs to recipient cells. For instance, BM-MSC-EVs containing miR-1246 can suppress Th17-mediated pathogenesis in periodontitis by downregulating angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 expression and modulating YAP1/Hippo signaling [11].

Integrated View of Soluble Factor Signaling

The diagram below illustrates how soluble factors secreted by MSCs coordinate to regulate different immune cell populations:

Experimental Approaches for Mechanism Separation

Disentangling the contributions of cell-cell contact versus soluble factors requires specialized experimental methodologies that allow for controlled cellular interactions.

Insert Co-Culture System

The insert co-culture system represents a gold standard technique for studying paracrine signaling in the absence of direct cellular contact [12]. This system utilizes permeable membrane-based inserts that fit into multiwell tissue culture plates, allowing one cell type (e.g., MSCs) to be cultured in the insert while another cell type (e.g., immune cells) is cultured in the well below. The microporous membrane permits the free diffusion of secreted soluble factors while preventing physical contact between the two cell populations [12]. Various membrane materials are available, including polyester (PET), polycarbonate (PC), or collagen-coated polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), with pore sizes typically ranging from 0.4 µm to 12.0 µm, selected based on the specific experimental requirements [12].

Protocol for Insert Co-Culture Setup [12]:

- Insert Preparation: Unwrap sterile inserts from packaging and place them in an empty multiwell tissue culture plate under sterile conditions.

- Cell Seeding: Seed the first cell type (e.g., MSCs) into the inserts at the appropriate density. Simultaneously, seed the second cell type (e.g., immune cells) in the wells of the tissue culture plate.

- Assembly: Carefully place the inserts containing the first cell type into the wells containing the second cell type, ensuring no air bubbles are trapped beneath the membrane.

- Culture Conditions: Incubate the co-culture system under standard conditions (e.g., 37°C, 5% CO₂) for the desired duration, typically 24-72 hours for most immunomodulation studies.

- Analysis: Following co-culture, cells in both compartments can be harvested for functional assays (e.g., proliferation, activation status), and conditioned media can be collected for analysis of secreted factors.

Advanced Single-Cell Secretion Profiling

Recent technological advances have enabled more sophisticated analysis of cell-cell interactions through integrative single-cell secretion profiling [13]. This platform utilizes an antibody-barcode microchip that simultaneously detects various secreted factors (multiple proteins and extracellular vesicle phenotypes), spatial distances, and migration information from high-throughput paired single cells [13]. The microchip consists of a high-density microchamber array (approximately 10,000 chambers) and a glass slide patterned with spatially resolved antibodies, allowing for multiplexed detection of proteins (e.g., IL-8, IL-6, MCP-1, IL-1β) and EV markers (CD9, CD81, CD63) with high sensitivity (detection limit of 40 pg mL⁻¹ for proteins and ∼3 × 10⁴ particles µL⁻¹ for EVs) [13].

Quantitative Comparison of Immunomodulatory Mechanisms

The relative contribution of contact-dependent versus soluble factor-mediated mechanisms varies depending on the specific immune cell target and environmental context. The table below summarizes key quantitative data from studies that have dissected these dual mechanisms.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Contact-Dependent vs. Soluble Factor-Mediated Immunomodulation by MSCs

| Immune Cell Target | Contact-Dependent Effects | Soluble Factor-Mediated Effects | Experimental System | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T Cells | Upregulation of ICAM-1/VCAM-1 critical for suppression; Induction of T-cell anergy; Notch1/FOXP3 pathway activation increases CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Tregs. | IDO-mediated tryptophan depletion inhibits proliferation; TGF-β and IL-10 suppress activation via Smad/STAT3; PGE2 inhibits Th17 differentiation. | Insert co-culture; Transwell systems; Single-cell secretion profiling | [7] [11] [13] |

| B Cells | Contact-dependent enhancement of quiescent B-cell survival; p38 MAPK-mediated cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 phase. | Conflicting reports on soluble factor effects: some studies show inhibition, others show promotion of proliferation and differentiation. | Direct co-culture vs. conditioned media experiments | [7] [11] |

| Macrophages | Phagocytosis of MSCs by monocytes induces phenotypic and functional changes. | PGE2 secretion drives switch from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype. | Insert co-culture; In vivo tracking studies | [7] [11] |

| Tumor Microenvironment | ECM and surface proteins of normal fibroblasts mediate contact-dependent inhibition of tumor cell proliferation. | Soluble factors (GDF15, DKK1, EMAPII) in confronted conditioned media (CCM) inhibit both tumor cell proliferation and motility. | Fibroblast-tumor cell co-culture systems | [14] |

Table 2: Key Soluble Factors in MSC-Mediated Immunomodulation and Their Detection Methods

| Soluble Factor | Primary Function in Immunomodulation | Detection Method | Approximate Detection Limit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) | Tryptophan catabolism, T-cell suppression, Treg induction | HPLC, ELISA | Varies by method |

| Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) | M1 to M2 macrophage switch, Th17 inhibition | ELISA, Mass Spectrometry | ~15 pg/mL (ELISA) |

| Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) | T-cell suppression via Smad pathway | ELISA, Single-cell barcode chip | ~40 pg/mL (chip) |

| Extracellular Vesicles (CD9+/CD81+/CD63+) | miRNA transfer, intercellular communication | Nanoparticle tracking, Microchip immunoassay | ~3×10⁴ particles/μL (chip) |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) & IL-8 | Pro-inflammatory regulation in tumor microenvironment | ELISA, Single-cell barcode chip | ~40 pg/mL (chip) |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful investigation of MSC immunomodulatory mechanisms requires specific research tools and reagents. The following table details essential components for designing appropriate experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying MSC Immunomodulatory Mechanisms

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Specific Examples & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Transwell/Insert Systems | Physically separates cell populations while allowing soluble factor exchange. | Polyester (PET), polycarbonate (PC), or collagen-coated PTFE membranes with pore sizes from 0.4-12.0 μm; used for paracrine signaling studies [12]. |

| Cell Tracking Dyes | Enables visualization and distinction of different cell populations in co-culture. | CellTracker DIO and DID membrane dyes; used for monitoring cellular interactions and migration in single-cell pairing experiments [13]. |

| Cytokine Detection Arrays | Multiplexed detection of secreted soluble factors. | Antibody-barcode microchips for proteins (IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, IL-1β) and EV markers (CD9, CD81, CD63) [13]. |

| TLR Agonists/Antagonists | Modulates MSC polarization state for mechanistic studies. | LPS (TLR4 agonist) for pro-inflammatory MSC1 polarization; Poly(I:C) (TLR3 agonist) for immunosuppressive MSC2 polarization [10]. |

| Neutralizing Antibodies | Blocks specific ligand-receptor interactions to test molecular mechanisms. | Antibodies against ICAM-1, VCAM-1, PD-L1, Galectin-1 to inhibit contact-dependent pathways [7]. |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | Blocks specific soluble factor production or signaling. | IDO inhibitors (1-MT), COX-2 inhibitors (to block PGE2 production) for dissecting soluble mediator pathways [7] [11]. |

The dual mechanism paradigm of cell-cell contact and soluble factor secretion underpins the remarkable immunomodulatory capacity of mesenchymal stem cells. Both mechanisms work in concert, often synergistically, to achieve precise spatial and temporal regulation of immune responses. The contact-mediated pathway provides targeted, specific regulation through direct molecular interactions, while the soluble factor pathway offers broader, more diffuse modulation of the tissue microenvironment. The relative contribution of each mechanism is highly dynamic and context-dependent, influenced by factors such as the tissue type, inflammatory milieu, and specific immune cell populations involved [10] [15]. Understanding this sophisticated duality is not merely an academic exercise but is crucial for optimizing MSC-based therapies, engineering enhanced MSC products, and developing novel pharmacological approaches that mimic these natural immunoregulatory mechanisms for treating a wide spectrum of immune-mediated diseases. Future research should focus on quantitatively mapping the interplay between these pathways in specific disease contexts to enable more precise therapeutic interventions.

Within the framework of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) immunomodulation research, a critical area of investigation involves understanding how MSCs orchestrate the functions of innate immune cells. Innate immunity serves as the body's first line of defense, comprising cells that initiate rapid responses to pathogens and abnormal cells [16]. Key cellular mediators include macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and natural killer (NK) cells, which participate in phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and direct cytotoxicity, respectively [17]. The immunomodulatory capabilities of MSCs significantly influence these cells, polarizing their phenotypes and altering their functional outputs to resolve inflammation and promote tissue repair [18] [19]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the mechanisms by which MSCs and their derived products modulate these innate immune cells, detailing specific pathways, experimental methodologies, and key research reagents essential for advancing therapeutic development.

Mechanisms of Innate Immune Cell Modulation by MSCs

Macrophage Regulation

Macrophages demonstrate remarkable plasticity, capable of adopting pro-inflammatory (M1) or anti-inflammatory, pro-repair (M2) phenotypes. MSCs potently influence this polarization, primarily through paracrine signaling, to suppress damaging inflammation and promote tissue healing [18] [19].

Key Mechanisms:

- Soluble Factor Secretion: MSCs release anti-inflammatory molecules like TNF-α-stimulated gene/protein 6 (TSG-6) and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA). TSG-6 modifies the CD44 receptor on macrophages, suppressing nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) signaling and reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α [19]. This pathway is critical in mitigating sepsis and other hyperinflammatory conditions.

- Metabolic Reprogramming and Trained Immunity: The concept of "trained immunity" describes the long-term functional reprogramming of innate immune cells like macrophages following an initial stimulus, leading to an enhanced response to secondary challenges [20]. This process is orchestrated by distinct metabolic and epigenetic rewiring. MSCs can influence this program through the Dectin-1/Akt/mTOR/HIF1α pathway and the NOD2/NF-κB pathway. Key metabolic shifts include upregulation of glycolysis, glutaminolysis, and cholesterol synthesis, leading to accumulation of metabolites like fumarate and succinate. These metabolites act as cofactors for epigenetic enzymes such as histone demethylases, resulting in activating histone marks (e.g., H3K4me3) on promoters of pro-inflammatory genes, thereby potentiating macrophage function [20].

- Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Communication: Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSCex) carry a cargo of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids that modulate macrophage activity. These exosomes can deliver miRNAs and cytokines directly to macrophages, promoting their polarization towards the M2 phenotype and enhancing their phagocytic capacity [21].

Table 1: Mechanisms of MSC-Mediated Macrophage Modulation

| Mechanism | Key MSC-Derived Effectors | Signaling Pathways in Macrophage | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soluble Factor Secretion | TSG-6, IL-1RA, PGE2 | NF-κB suppression, STAT3 activation | Reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6); Increased IL-10; M2 polarization [18] [19] |

| Metabolic Reprogramming | Influences via paracrine signals | Dectin-1/Akt/mTOR/HIF1α, NOD2/NF-κB, Glycolysis upregulation | Epigenetic rewiring (H3K4me3), enhanced cytokine production, "trained immunity" [20] |

| Extracellular Vesicles | Exosomes containing miRNAs, proteins | Transfer of bioactive cargo | M2 polarization, enhanced phagocytosis, anti-inflammatory response [21] |

Dendritic Cell Regulation

Dendritic cells are professional antigen-presenting cells that bridge innate and adaptive immunity. MSCs inhibit the maturation and antigen-presenting capacity of DCs, thereby dampening T cell activation and promoting immune tolerance [18] [22].

Key Mechanisms:

- Inhibition of Maturation: MSCs prevent the upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules (CD80, CD86) and MHC class II on DC surfaces, which is essential for effective T cell priming. This results in the generation of tolerogenic DCs that induce T cell anergy or promote the expansion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) [18] [23].

- Cell-Cell Contact and Soluble Factors: The immunomodulatory effects are mediated through both cell-cell contact, involving molecules like programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), and soluble factors such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and galectin-1. Knocking down galectin-1 in MSCs diminishes their capacity to suppress allogeneic T cell responses [18].

Table 2: Effects of MSCs on Dendritic Cell Phenotype and Function

| Parameter | Effect of MSC Co-Culture | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Maturation Markers | ↓ CD80, CD86, CD83, MHC-II [18] | Impaired antigen presentation |

| Cytokine Secretion | ↓ IL-12, ↑ IL-10 [18] | Promotion of immune tolerance |

| T cell Priming | Inhibition of naive and memory T cell activation [18] | Suppression of adaptive immune response |

| Chemotaxis | Altered migration and adhesion | Reduced homing to lymph nodes |

Natural Killer (NK) Cell Regulation

NK cells are cytotoxic lymphocytes that eliminate virus-infected and tumor cells. MSC-mediated regulation of NK cells is bidirectional, involving both suppression of proliferation and cytotoxicity and facilitation of their activation under specific conditions [24] [18].

Key Mechanisms:

- Suppression of Proliferation and Cytotoxicity: MSCs inhibit IL-2 and IL-15-induced NK cell proliferation and cytokine production (e.g., IFN-γ). They also downregulate the expression of activating receptors (e.g., NKp30, NKG2D) on NK cells, thereby blunting their cytotoxic activity. This is achieved through the release of soluble mediators like PGE2, TGF-β, and IDO [18].

- Orchestration of NK Activity: A pivotal mechanism involves the Dectin-1 receptor on dendritic cells and macrophages. Dectin-1 recognition of tumor cells expressing high levels of N-glycan structures activates the IRF5 transcription factor. This pathway is critical for inducing the full tumoricidal activity of NK cells. Mice deficient in Dectin-1 or IRF5 show exacerbated tumor growth, underscoring the importance of this cross-talk between innate immune cells for effective NK-mediated anti-tumor responses [24].

- Conditioning-Dependent Effects: The state of MSC activation influences their impact on NK cells. MSCs conditioned with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) exhibit enhanced immunomodulatory activity, which can more effectively modulate NK cell function compared to resting MSCs [22].

(Diagram 1: Dectin-1-IRF5 Pathway in NK Cell Orchestration)

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol 1: Assessing Macrophage Polarization via MSC Co-Culture

Objective: To evaluate the effect of MSCs or MSC-derived exosomes on macrophage polarization from M1 to M2 phenotype.

Materials:

- Primary human monocytes isolated from PBMCs or a human monocyte cell line (e.g., THP-1).

- Human MSCs (e.g., adipose-derived or bone marrow-derived).

- Differentiation and polarization cytokines: GM-CSF, M-CSF, IFN-γ, LPS, IL-4, IL-13.

- FACS buffer and antibodies for M1/M2 markers: CD80, CD86, CD38, CD163, CD206, MHC-II.

Methodology:

- Monocyte-derived Macrophage Generation: Isolate CD14+ monocytes from PBMCs using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS). Differentiate monocytes into macrophages by culturing with 50 ng/mL M-CSF for 6 days.

- M1 Polarization: Polarize macrophages towards an M1 phenotype by stimulating with 100 ng/mL LPS and 20 ng/mL IFN-γ for 24-48 hours.

- Co-culture Setup: Establish a transwell co-culture system. Place M1-polarized macrophages in the lower chamber and MSCs (at a 1:5 macrophage:MSC ratio) in the upper chamber. Include control wells with M1 macrophages alone.

- Analysis:

- Flow Cytometry: After 48-72 hours of co-culture, harvest macrophages and stain for surface M1 (CD80, CD86) and M2 (CD163, CD206) markers. Analyze using flow cytometry.

- Cytokine Profiling: Collect culture supernatants and measure cytokine levels (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6 for M1; IL-10, TGF-β for M2) via ELISA or multiplex bead-based assays.

- Gene Expression: Extract RNA from macrophages and perform qRT-PCR to analyze the expression of M1 (iNOS, IL-1β) and M2 (Arg1, Ym1) marker genes [21] [18].

Protocol 2: Evaluating DC Maturation and Function

Objective: To determine the inhibitory effect of MSCs on the maturation and T cell-stimulatory capacity of dendritic cells.

Materials:

- Immature DCs (generated from monocytes with GM-CSF and IL-4).

- MSCs (resting or conditioned).

- LPS for maturation.

- CFSE-labeled allogeneic T cells.

- Antibodies: CD83, CD86, HLA-DR, CD3, CD4.

Methodology:

- DC Generation and MSC Conditioning: Differentiate CD14+ monocytes into immature DCs (imDCs) using 100 ng/mL GM-CSF and 50 ng/mL IL-4 for 5-7 days. Optionally, condition MSCs by co-culturing with PBMCs or pre-treating with IFN-γ (50 ng/mL for 24-48 hours) to enhance their immunomodulatory potency [22].

- Inhibition of Maturation: Co-culture imDCs with MSCs (e.g., 1:10 DC:MSC ratio) in a transwell system or direct contact system. Activate DC maturation by adding 100 ng/mL LPS for the final 24 hours of co-culture.

- Flow Cytometric Analysis: Harvest DCs and stain for maturation markers (CD83, CD86, HLA-DR). Analyze using flow cytometry to assess the percentage of mature DCs and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of markers.

- Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction (MLR): Collect DCs from the co-culture, irradiate them to prevent proliferation, and co-culture them with CFSE-labeled allogeneic CD4+ T cells. After 5 days, analyze T cell proliferation by measuring CFSE dilution via flow cytometry. Suppressed T cell proliferation indicates impaired DC function [18] [22] [23].

Protocol 3: Analyzing NK Cell Cytotoxicity and Proliferation

Objective: To investigate the modulation of NK cell function by MSCs, focusing on proliferation, receptor expression, and cytotoxic activity.

Materials:

- Isolated human NK cells (e.g., CD56+ from PBMCs).

- MSCs (resting and PBMC-conditioned).

- Target cells (e.g., K562 erythroleukemia cell line).

- IL-2 and IL-15.

- Antibodies: CD56, CD16, NKp30, NKp46, NKG2D, Annexin V, 7-AAD.

Methodology:

- NK Cell Isolation and MSC Co-culture: Isolate NK cells from PBMCs using a negative selection kit. Co-culture purified NK cells with MSCs (e.g., 1:5 MSC:NK ratio) in the presence of 100 U/mL IL-2 and 10 ng/mL IL-15 for 48-72 hours.

- Proliferation and Phenotype Analysis: Label NK cells with CFSE prior to co-culture to track proliferation. After co-culture, analyze CFSE dilution by flow cytometry. Simultaneously, stain NK cells for activating (NKp30, NKG2D) and inhibitory receptors.

- Cytotoxicity Assay: Use a standard calcein-AM release assay or real-time cell analysis. Label K562 target cells with calcein-AM. Co-culture effector NK cells (from co-culture) with target cells at various effector-to-target (E:T) ratios (e.g., 10:1, 5:1) for 4 hours. Measure fluorescence released from lysed target cells. Calculate specific lysis percentage [24] [18].

- Dectin-1 Pathway Investigation: To study the orchestration mechanism, use a Dectin-1 agonist (e.g., β-glucan) or antagonist in a triple-culture system of DCs, MSCs, and NK cells, and assess the subsequent NK cell cytotoxicity against tumor targets.

(Diagram 2: General Workflow for MSC-Immune Cell Co-culture Studies)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying MSC-Mediated Innate Immune Modulation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Surface Markers (Flow Cytometry) | CD14, CD68, CD80 (M1 Macrophage), CD163, CD206 (M2 Macrophage), CD83, CD86 (DC Maturation), CD56, CD16, NKp30, NKp46 (NK Cells) | Phenotypic identification and functional characterization of innate immune cell subsets. | [17] |

| Cytokines & Growth Factors | M-CSF, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-13, IL-2, IL-15, TNF-α | Differentiation, polarization, and functional activation of macrophages, DCs, and NK cells. | [18] [22] |

| Inhibitors & Agonists | Rapamycin (mTOR inhibitor), Metformin, β-Glucan (Dectin-1 agonist), LPS (TLR4 agonist) | Dissecting specific signaling pathways (e.g., Dectin-1/Akt/mTOR) in trained immunity and cell activation. | [20] |

| MSC Conditioning Agents | Recombinant IFN-γ, TNF-α, Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMC) | Priming MSCs to enhance their immunomodulatory potency prior to functional assays. | [22] |

| Critical Assay Kits | ELISA/Multiplex Cytokine Kits (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12), CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit, LDH/Caspase Cytotoxicity Assays | Quantifying soluble factors, immune cell proliferation, and cytotoxic activity. | [24] [18] |

The strategic orchestration of innate immunity by mesenchymal stem cells, particularly their nuanced effects on macrophages, dendritic cells, and NK cells, represents a cornerstone of their therapeutic mechanism. This interplay, mediated by a complex network of soluble factors, cell-cell contacts, extracellular vesicles, and the induction of metabolic-epigenetic programs like trained immunity, highlights the sophistication of MSC-mediated immunomodulation. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of these mechanisms and the associated experimental tools is paramount. The continued refinement of MSC conditioning protocols and the precise dissection of these innate immune pathways are critical for developing next-generation, cell-based therapies with enhanced efficacy for treating inflammatory, autoimmune, and oncological diseases.

The adaptive immune system, characterized by its high specificity and memory, is orchestrated primarily by T and B lymphocytes [25]. Within this system, CD4+ T helper (Th) cells play a pivotal role in directing immune responses. Their differentiation into distinct subsets—such as Th1, Th2, and Th17—is controlled by specific transcription factors and cytokine environments, while their activity is counterbalanced by immunosuppressive regulatory T cells (Tregs) [26] [27]. The precise regulation of the balance between these effector and regulatory cells is critical for maintaining immune homeostasis, preventing autoimmune reactions, and resolving inflammation. Research into mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) immunomodulation has provided profound insights into these processes. MSCs possess a remarkable capacity to suppress T-cell proliferation, shift the Th1/Th2 balance, and induce Treg formation, making them a powerful model system for studying and harnessing these mechanisms for therapeutic purposes [28] [29]. This whitepaper delves into the core mechanisms of adaptive immune regulation, framing the discussion within the context of MSC research and providing detailed experimental data and methodologies.

Core Mechanisms of T-cell Suppression

Metabolic Disruption via Tryptophan Starvation

A primary mechanism of T-cell suppression, particularly by human MSCs, involves the induction of metabolic stress through amino acid deprivation. The enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), produced by MSCs in response to inflammatory signals like interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), catalyzes the degradation of the essential amino acid tryptophan in the local microenvironment [30].

- Mechanism of Action: IDO consumption of tryptophan creates a local deficiency. Activated T cells, which have a high demand for tryptophan for protein synthesis and proliferation, are particularly sensitive to this deprivation. This starvation does not primarily inhibit mTOR or activate the ATF2 pathway but instead induces endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in the T cells, leading to a potent arrest of proliferation [30].

- Experimental Evidence: The critical role of tryptophan starvation, as opposed to the accumulation of tryptophan catabolites (kynurenines), was demonstrated by rescuing T-cell proliferation in IDO+ conditioned media through tryptophan supplementation, but not with kynurenine addition [30]. The response to tryptophan concentration is notably sharp, exhibiting a near-binary "all-or-nothing" switch over a very narrow dynamic range (a 10-fold change in concentration) [30].

Table 1: Quantitative Data on IDO-Mediated T-cell Suppression

| Experimental Condition | T-cell Proliferation (Cells/mL ± SD) | IL-2 Secretion (pg/mL ± SD) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum-Free Media (SFM - 21% O₂) | 5.3 × 10⁵ ± 1.8 × 10⁴ | 5305 ± 211 | [28] |

| Serum-Free Media (SFM - 2% O₂) | 5.1 × 10⁵ ± 3.0 × 10⁴ | 5347 ± 327 | [28] |

| MSC Conditioned Media (SFCM - 21% O₂) | 2.4 × 10⁵ ± 2.5 × 10⁴ | 2461 ± 178 | [28] |

| MSC Conditioned Media (SFCM - 2% O₂) | 2.2 × 10⁵ ± 5.8 × 10³ | 1625 ± 159 | [28] |

Soluble Factor-Mediated Suppression

Beyond IDO, MSCs and their secretome employ a cocktail of soluble factors to suppress T-cell activity.

- Anti-inflammatory Cytokines: The MSC secretome is rich in cytokines like IL-10, which plays a non-redundant role in immunosuppression. Neutralization of IL-10 in MSC-conditioned media restores T-cell proliferation, whereas neutralization of IL-4 or IL-13 does not, highlighting its specific and critical function [28]. Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β) is another key immunosuppressive cytokine involved in MSC-mediated T-cell inhibition [29].

- Other Mediators: In mice, which do not utilize IDO for this purpose, nitric oxide (NO) is a major mediator of T-cell suppression, ultimately also leading to the induction of cellular stress [30].

Regulation of Th1/Th2 Balance and T Helper Cell Polarization

The balance between pro-inflammatory Th1 cells and anti-inflammatory Th2 cells is a crucial determinant of immune outcome. MSCs have been demonstrated to skew the immune response away from Th1 and toward a Th2 phenotype [29].

- Th1 Differentiation: Driven by the cytokine IL-12 and the master transcription factor T-bet (Tbx21). Th1 cells typically produce IFN-γ and are critical for combating intracellular pathogens [27].

- Th2 Differentiation: Driven by the cytokine IL-4 and the master transcription factor GATA3. Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, which are important for antibody class switching and responses to parasites, but also central to allergic inflammation [26] [27].

- MSC-Mediated Shifting: MSCs, through their secretome and interactions with antigen-presenting cells, can suppress the production of Th1-polarizing cytokines like IL-12 while promoting a Th2-favoring environment. This results in a measured shift from a pro-inflammatory Th1 to an anti-inflammatory Th2 profile, which is beneficial in contexts like autoimmune disease and allograft rejection [29].

Induction and Function of Regulatory T Cells (Tregs)

The induction of Tregs is a cornerstone of MSC-mediated immunomodulation. Tregs, characterized by the expression of the transcription factor Foxp3, are essential for maintaining peripheral tolerance and limiting immune responses [26] [29].

Mechanisms of Treg Induction

MSCs promote the generation of Tregs through multiple, synergistic pathways:

- Soluble Factors: MSC-secreted factors like TGF-β1 and IL-10 directly promote the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into Foxp3+ Tregs [29]. The enzyme IDO also contributes to Treg induction [29].

- Monocyte-Mediated Induction: MSCs reprogram monocytes/macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory (type 2) phenotype. These MSC-primed monocytes, in turn, produce high levels of CCL-18 and TGF-β1, which are potent inducers of Treg formation from naive CD4+ T cells [29].

- Direct Cell Contact: In some contexts, direct contact between MSCs and T cells or other immune cells can contribute to Treg induction, although the exact mechanisms are less defined [29].

The Complex Interplay Between Th2 and Treg Pathways

While Th2 cells and Tregs are distinct lineages, their developmental pathways are more intertwined than previously thought. Key Th2 components also play critical roles in Treg biology:

- IL-4: Traditionally a Th2-driver, IL-4 signaling is also vital for maintaining the immunosuppressive function of Tregs. Tregs lacking IL-4 signaling have impaired expression of regulatory molecules like IL-10, granzyme A, and granzyme B, leading to reduced suppressive capacity [27].

- Transcription Factors: The Th2 master regulator GATA3 is also expressed in a subset of Tregs and is important for their stability and function. Furthermore, the transcription factor IRF4, critical for Th2 differentiation, is induced by Foxp3 in Tregs and is specifically required for Tregs to suppress Th2-mediated responses [26] [27].

Diagram 1: Integrated Network of MSC-Mediated Immunomodulation. This diagram illustrates the synergistic actions of MSC-derived soluble factors on various immune cells, leading to T-cell suppression and Treg induction.

Experimental Models & Methodologies

In Vitro T-cell Suppression and Proliferation Assay

This is a foundational protocol for assessing the immunomodulatory capacity of MSCs or their secretome.

- Objective: To quantify the suppression of T-cell proliferation by MSC-conditioned media.

- Materials:

- Jurkat T cells or primary human CD4+ T cells isolated from peripheral blood.

- MSCs (e.g., bone marrow-derived or dental pulp-derived).

- T-cell activation reagents: Anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies.

- Cell proliferation dye: CFSE (Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester).

- Serum-free media (SFM) and IFN-γ to "license" MSCs.

- IDO inhibitor: 1-Methyl-DL-tryptophan (1-MT).

- Procedure:

- Generate Conditioned Media: Culture MSCs in serum-free media with IFN-γ (e.g., 10-20 ng/mL) for 24-48 hours to generate "licensed" conditioned media (γCM). Control media is from unlicensed MSCs (CM) [30].

- Label T cells: Isolate and label CD4+ T cells with CFSE according to standard protocols.

- Activate and Culture: Activate CFSE-labeled T cells with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies. Culture the activated T-cells in:

- 100% SFM (positive control)

- 100% γCM (test condition)

- 100% γCM + IDO inhibitor (e.g., 1-MT) or supplemental tryptophan (rescue condition) [30].

- Incubate and Analyze: Culture cells for 72-96 hours. Analyze proliferation by flow cytometry via CFSE dilution. Quantify cytokine secretion (e.g., IL-2) in supernatants by ELISA [28].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for T-cell Immunomodulation Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-CD3/CD28 Antibodies | Polyclonal T-cell receptor activation. | Positive control for T-cell proliferation and IL-2 secretion [28]. |

| CFSE (Proliferation Dye) | Fluorescent cell tracing dye that dilutes with each cell division. | Quantifying the extent of T-cell proliferation inhibition by MSC secretome [30]. |

| Recombinant IFN-γ | Inflammatory cytokine to "license" or prime MSCs. | Inducing high expression of immunomodulatory genes like IDO in MSCs [30]. |

| IDO Inhibitor (1-MT) | Competitive inhibitor of the IDO enzyme. | Mechanistic studies to confirm the role of IDO in T-cell suppression [30]. |

| Neutralizing Antibodies (e.g., anti-IL-10) | Bind to and block the activity of a specific cytokine. | Identifying the specific soluble factors responsible for observed immunomodulatory effects [28]. |

Cytokine Neutralization Studies

- Objective: To identify the specific soluble factors responsible for MSC-mediated effects.

- Procedure: Co-culture activated T cells with MSC-conditioned media in the presence of neutralizing antibodies against specific cytokines (e.g., anti-IL-10, anti-IL-4, anti-IL-13, anti-TGF-β). Compare proliferation and cytokine profiles to isotype control conditions. Restoration of proliferation upon neutralization identifies a critical mediator, as demonstrated for IL-10 [28].

Diagram 2: IL-10 Mediated Suppression of T-cell Proliferation. This flowchart details the mechanism by which MSC-derived IL-10 suppresses IL-2 secretion, a critical growth factor, leading to the arrest of T-cell proliferation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

A curated list of essential materials for studying immunomodulation, derived from the experimental protocols cited.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit for Immunomodulation Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-CD3/CD28 Antibodies | Polyclonal T-cell receptor activation. | Positive control for T-cell proliferation and IL-2 secretion [28]. |

| CFSE (Proliferation Dye) | Fluorescent cell tracing dye that dilutes with each cell division. | Quantifying the extent of T-cell proliferation inhibition by MSC secretome [30]. |

| Recombinant IFN-γ | Inflammatory cytokine to "license" or prime MSCs. | Inducing high expression of immunomodulatory genes like IDO in MSCs [30]. |

| IDO Inhibitor (1-MT) | Competitive inhibitor of the IDO enzyme. | Mechanistic studies to confirm the role of IDO in T-cell suppression [30]. |

| Neutralizing Antibodies (e.g., anti-IL-10) | Bind to and block the activity of a specific cytokine. | Identifying the specific soluble factors responsible for observed immunomodulatory effects [28]. |

The regulation of adaptive immunity through T-cell suppression, Th1/Th2 balancing, and Treg induction represents a sophisticated network of checks and balances. Research into mesenchymal stem cells has been instrumental in elucidating these mechanisms, revealing a multi-faceted strategy involving metabolic disruption (IDO), soluble factor mediation (IL-10, TGF-β), and re-education of innate immune cells to promote tolerance. The experimental data and methodologies outlined herein provide a framework for continued investigation. A deeper understanding of these principles, particularly the nuanced interplay between effector and regulatory pathways, is paramount for advancing therapeutic strategies aimed at treating autoimmune diseases, preventing transplant rejection, and managing pathological inflammation.

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) exert their potent immunomodulatory effects primarily through paracrine signaling, with soluble mediators serving as critical mechanistic components. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of five key soluble factors—Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β), Tumor Necrosis Factor-Stimulated Gene 6 (TSG-6), and Human Leukocyte Antigen-G5 (HLA-G5). Within the context of MSC research, these mediators represent promising targets for therapeutic development in autoimmune diseases, transplant medicine, and cancer. We present structured quantitative data, experimental protocols, signaling pathway visualizations, and essential research reagents to facilitate advanced research and drug development efforts.

The immunomodulatory capacity of mesenchymal stromal cells constitutes a fundamental research focus in regenerative medicine and immunotherapy. MSCs interact with both innate and adaptive immune systems through two primary mechanisms: direct cell-to-cell contact and secretion of soluble factors [29] [6]. While cell contact-dependent mechanisms involving PD-L1/PD-1 interactions and adhesion molecules are well-documented, the soluble mediator component offers broader therapeutic potential for cell-free therapies [31]. Recent research has demonstrated that the MSC secretome contains both soluble factors and extracellular vesicles, with each fraction modulating different immune pathways [32]. The complex synergy between these mediators allows MSCs to dynamically respond to inflammatory cues and restore immune homeostasis, making them promising candidates for treating autoimmune conditions, managing graft-versus-host disease, and modulating cancer immunotherapy responses [33] [6].

Comprehensive Profile of Key Soluble Mediators

Table 1: Core Functional Properties of Key Immunomodulatory Mediators

| Mediator | Full Name | Primary Cellular Source | Key Immunomodulatory Functions | Major Target Immune Cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDO | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase | MSCs, Dendritic Cells, Macrophages | Tryptophan catabolism to kynurenine, T effector cell suppression, Treg differentiation | T cells, NK cells, DCs |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 | MSCs, Macrophages | Inhibition of DC maturation, macrophage polarization to M2 phenotype, T cell suppression | Macrophages, Dendritic Cells, T cells |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-beta | MSCs, Tregs, Macrophages | Treg differentiation, suppression of T cell proliferation, B cell inhibition | T cells, B cells, Macrophages |

| TSG-6 | TNF-Stimulated Gene 6 | MSCs, Macrophages | Anti-inflammatory protein, macrophage polarization, neutrophil migration inhibition | Macrophages, Neutrophils |

| HLA-G5 | Human Leukocyte Antigen-G5 | MSCs, Placental cells | Inhibition of NK and cytotoxic T cells, Treg induction, tolerance induction | NK cells, T cells, APCs |

Table 2: Quantitative Characteristics and Experimental Detection Methods

| Mediator | Molecular Weight (kDa) | Detection Methods | Common Assays | Key Regulatory Cues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDO | ~45 kDa | ELISA, Western Blot, HPLC | Kynurenine assay, IDO activity assay | IFN-γ, TNF-α, Bin1, STAT1/NF-κB pathways |

| PGE2 | 0.352 kDa | ELISA, Mass Spectrometry | Competitive EIA, PGE2 Express ELISA Kit | COX-2, TNF-α, IL-1β, cell-cell contact |

| TGF-β | 25 kDa (latent) | ELISA, Luminex, Bioassay | Bioassay with reporter cells, CAGA-luciferase | Integrins, proteases, pH changes |

| TSG-6 | ~35 kDa | ELISA, Western Blot | Hyaluronan binding assay, neutrophil migration assay | NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-1β |

| HLA-G5 | ~37 kDa (monomer) | Flow Cytometry, ELISA | Soluble HLA-G ELISA, Western Blot | Inflammation, cell stress, cytokines |

Table 3: Signaling Pathways and Downstream Effects

| Mediator | Receptor | Primary Signaling Pathways | Downstream Gene Regulation | Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDO | AhR (via kynurenine) | GCN2 kinase, mTOR inhibition, AhR activation | FOXP3, IL-10, IL-6 | T cell anergy, Treg differentiation, NK cell suppression |

| PGE2 | EP2/EP4 receptors | cAMP-PKA signaling, CREB activation | IL-10, TGF-β, IDO1 | DC maturation inhibition, M2 macrophage polarization |

| TGF-β | TGF-βRI/II | Smad2/3 phosphorylation, SMAD4 complex | FOXP3, CTLA-4, IL-2 inhibition | Treg differentiation, Th17 inhibition, B cell suppression |

| TSG-6 | CD44, HA receptors | NF-κB modulation, protease inhibition | TNF-α, IL-6, MMPs | Anti-inflammatory, ECM protection, macrophage reprogramming |

| HLA-G5 | ILT2/KIR2DL4 | JAK/STAT, NF-κB inhibition | Perforin, Granzyme B, IFN-γ | NK cell inhibition, cytotoxic T cell suppression, APC tolerance |

Detailed Experimental Methodologies

IDO Functional Analysis Protocol

Objective: Quantify IDO-mediated immunomodulation through kynurenine production and T cell suppression assays.

Materials:

- THP-1 dual reporter cell line (Invivogen)

- Human PBMCs from healthy donors

- IDO activity assay kit (Immusmol)

- Recombinant IFN-γ for IDO induction

- 1-Methyl-tryptophan (1-MT) as IDO inhibitor

- Ultracentrifugation equipment (150,000 × g capability)

- Flow cytometer with T cell proliferation dyes (CFSE, CellTrace Violet)

Procedure:

- MSC Priming and Supernatant Collection:

Kynurenine Quantification:

- Incubate MSC-conditioned media with 100 μM L-tryptophan for 2 hours at 37°C

- Add 30% trichloroacetic acid to terminate reaction, centrifuge at 15,000 × g

- Transfer supernatant to 96-well plate, mix with equal volume of Ehrlich's reagent

- Measure absorbance at 490 nm, calculate kynurenine concentration against standard curve

T Cell Suppression Assay:

- Isolate PBMCs from healthy donors using Ficoll density gradient

- Label CD3+ T cells with proliferation dye (CFSE, 5 μM)

- Activate T cells with anti-CD3/CD28 beads or PHA/IL-2

- Co-culture with MSC-conditioned media or IDO-knockdown MSCs as control

- After 96 hours, analyze T cell proliferation by flow cytometry

- Measure CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Treg population using intracellular staining

PGE2 and Soluble Factor Isolation

Objective: Iscrete and quantify PGE2-mediated immunomodulation from MSC secretome.

Materials:

- Tangential Flow Filtration system with 5-100 kDa membranes

- Prostaglandin E2 Express ELISA Kit (Cayman Chemical)

- Ultracentrifugation equipment (150,000 × g)

- Bath sonicator for EV lysis

- Transwell co-culture systems

Procedure:

- Secretome Fractionation:

- Harvest MSC-conditioned media after 72-hour production phase

- Clarify through 0.45 μm filtration to remove cells/debris [32]

- Process through TFF with sequential molecular weight cutoffs (100 kDa, 30 kDa, 5 kDa)

- Validate fraction purity by nanoparticle tracking analysis and protein quantification

PGE2 Quantification:

- Lyse EV-containing fractions using bath sonication (3 × 10 min cycles) [32]

- Process samples using Prostaglandin E2 Express ELISA per manufacturer protocol

- Measure absorbance at 405-420 nm, calculate concentration from standard curve

Functional Validation:

- Use transwell systems to separate MSCs from immune cells while allowing soluble factor exchange [31]

- Treat PBMCs with resiquimod to activate NF-κB and IRF pathways

- Assess NF-κB inhibition in THP-1 dual reporter cells

- Compare immunosuppressive capacity of different secretome fractions

Diagram 1: Integrated signaling network of MSC-derived soluble mediators showing convergent immunomodulation through multiple pathways. Key interactions include IDO-mediated tryptophan metabolism and PGE2-driven macrophage polarization.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Soluble Mediator Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Product Examples | Primary Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDO Inhibitors | 1-Methyl-tryptophan (1-MT), Epacadostat, INCB024360 | IDO pathway validation, control experiments | Use dose range 100-500 μM for 1-MT; monitor viability |

| PGE2 Modulators | NS-398 (COX-2 inhibitor), Misoprostol (PGE1 analog) | PGE2 pathway manipulation, signaling studies | COX-2 inhibition reduces PGE2; confirm with ELISA |

| TGF-β Neutralizers | Anti-TGF-β antibodies, SB-431542 (ALK5 inhibitor) | TGF-β pathway blockade, functional studies | Validate specificity with phospho-Smad2/3 Western |

| ELISA Kits | Prostaglandin E2 Express ELISA (Cayman), Kynurenine/Tryptophan ELISA (Immusmol) | Quantitative mediator measurement | Follow sonication protocol for EV-containing samples [32] |

| Cell Separation | MACS Pan T Cell Isolation Kit, CD4+CD25+ Treg Isolation Kit | Immune cell isolation for co-culture studies | Maintain >95% purity for reproducible results |

| EV Isolation | Tangential Flow Filtration, Ultracentrifugation | Secretome fractionation, EV isolation | TFF preserves EV integrity better than ultracentrifugation [32] |

| Reporter Cells | THP-1 Dual NF-κB/IRF reporter cells (Invivogen) | Innate immunity pathway monitoring | Measure SEAP and Lucia luciferase for NF-κB/IRF |

Diagram 2: Comprehensive experimental workflow for MSC secretome analysis, from cell culture and priming to fractionation and functional characterization of soluble mediators.

Concluding Remarks and Research Implications

The sophisticated network of soluble immunomodulatory mediators represents a promising frontier for therapeutic development. Current evidence strongly supports the cooperative nature of IDO, PGE2, TGF-β, TSG-6, and HLA-G5 in mediating MSC-driven immunomodulation, with context-dependent dominance of different factors [32] [31]. Recent findings demonstrating that soluble factors under 5 kDa target innate immune pathways while larger components regulate T cell proliferation highlight the importance of fractionation approaches in therapeutic development [32].

Future research directions should prioritize defining optimal mediator combinations for specific disease contexts, engineering MSC lines with enhanced mediator expression [34], and developing standardized potency assays for clinical translation. The continued elucidation of these soluble mediator networks will undoubtedly yield novel immunomodulatory strategies with significant impact across transplantation, autoimmunity, and cancer therapeutics.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) represent a cornerstone of regenerative medicine and immunomodulation therapy, not as fixed-entity cells but as dynamic entities whose functional phenotypes are profoundly shaped by their microenvironment. This technical review examines the mechanisms through which physicochemical, biochemical, and cellular components of the microenvironment dictate MSC immunomodulatory plasticity. We synthesize current understanding of how factors including oxygen tension, soluble mediators, extracellular matrix, and heterotypic cell interactions direct MSC fate decisions and functional polarization through specific signaling pathways. The whitepaper provides structured quantitative data, detailed experimental methodologies, and visualization of critical mechanisms to equip researchers with tools for manipulating MSC phenotype in therapeutic contexts. Within the broader thesis of MSC immunomodulation research, this analysis underscores that targeting the microenvironment may offer more precise control over MSC function than direct cellular manipulation, potentially overcoming current limitations in clinical translation.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), multipotent stromal cells originating from various tissues, possess capabilities for self-renewal, multilineage differentiation, and extensive immunomodulation [35]. Their therapeutic potential extends across regenerative medicine, autoimmune diseases, and transplantation, primarily mediated through paracrine signaling and direct cell-cell contact. However, a fundamental characteristic complicating their clinical application is their remarkable plasticity—the ability to alter their phenotype, secretome, and functional properties in response to environmental cues [35].

The microenvironment (or niche) encompasses the complete milieu surrounding MSCs, including the extracellular matrix (ECM), neighboring cells (both homotypic and heterotypic), soluble factors (cytokines, growth factors, hormones), and physical conditions (oxygen tension, mechanical stresses) [36] [37]. The stability of this microenvironment is pivotal for maintaining normal cell proliferation, differentiation, metabolism, and functional activities. Conversely, abnormal changes in microenvironmental components can significantly disrupt MSC function [36]. This review systematically examines how specific microenvironmental elements dictate MSC immunomodulatory phenotype, providing researchers with frameworks for experimental investigation and therapeutic development.

Fundamental Mechanisms of MSC Plasticity

Defining Plasticity in MSCs

Plasticity in MSCs transcends multilineage differentiation potential. It encompasses dynamic changes in cell morphology, surface marker expression, proliferation rates, migration capacity, and immunomodulatory activity based on tissue source, disease context, and culture conditions [35]. This functional adaptability stems from the MSC's inherent responsiveness to environmental signals, allowing them to fulfill diverse physiological roles from tissue repair to immune regulation.

The plasticity manifestations observed in MSCs include:

- Morphological and Phenotypic Variations: MSCs demonstrate significant alterations in cell volume, cytoskeletal organization, and surface receptor expression under different pathological conditions [35].

- Functional Adaptations: Changes in proliferative capacity, differentiation bias, migration behavior, and paracrine secretion profiles occur in response to microenvironmental cues [35].

- Immunomodulatory Switch: MSCs can toggle between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory phenotypes, particularly in response to cytokine milieus [37].

Theoretical Framework of Plasticity Regulation

The plasticity of MSCs can be understood through the concept of noise-driven differentiation dynamics [38]. Computational models represent MSC differentiation states along a continuous spectrum, with individual cells exhibiting state fluctuations influenced by environmental parameters:

Diagram: Theoretical framework of noise-driven MSC plasticity. The differentiation state (α) fluctuates randomly with environment-dependent amplitude (σ(α)), enabling reversible transitions between states. Proliferation is restricted to progenitor states (αs<α<αd).

This model predicts that at low oxygen tension, the heterogeneity of an MSC population regenerates from any selected subpopulation within approximately two days, while high oxygen tension substantially slows this regenerative plasticity [38]. The model further suggests that most functional stem cells within a pool originate from more differentiated cells through de-differentiation processes.

Microenvironmental Factors Governing MSC Immunomodulation

Soluble Biochemical Factors

The soluble component of the MSC microenvironment includes cytokines, growth factors, chemokines, and metabolic products that profoundly influence immunomodulatory phenotype through specific signaling pathways.

Table 1: Key Soluble Factors Regulating MSC Immunomodulatory Plasticity

| Soluble Factor | Source | Effect on MSC Phenotype | Resulting Immunomodulatory Function | Molecular Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | Activated T cells, NK cells | induces immunosuppressive phenotype | enhances T-cell inhibition | Upregulates IDO, PD-L1, HLA-G [37] |

| TNF-α | Macrophages, dendritic cells | primes MSC immunomodulation | enhances anti-inflammatory secretion | activates NF-κB, increases TSG-6 production [35] |

| IL-1β | Monocytes, macrophages | pro-inflammatory priming | increases PGE2 secretion | COX-2 upregulation, PGE2 synthesis [37] |

| TGF-β | Tregs, platelets, MSCs | promotes regulatory functions | induces Treg differentiation, M2 polarization | Smad signaling, FoxP3 induction [37] |

| IL-6 | Macrophages, MSCs, T cells | context-dependent duality | both pro/anti-inflammatory effects | JAK/STAT signaling, neutrophil regulation [35] [37] |

| PGE2 | MSCs, macrophages | autocrine reinforcement | enhances M2 macrophage polarization | EP receptor signaling, cAMP activation [37] |

The context dependency of cytokine effects is particularly evident in factors like IL-6, which can exhibit both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties based on concentration, timing, and cellular target [39]. Similarly, the presence of IFN-γ is a critical determinant for acquiring T-cell inhibitory properties through indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) upregulation [37].

Physicochemical Factors

Physical and chemical parameters of the microenvironment, including oxygen tension, ECM stiffness, and biomechanical forces, significantly modulate MSC immunomodulatory function.

Oxygen Tension

Oxygen concentration serves as a master regulator of MSC plasticity through hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) and redox-sensitive signaling pathways:

Diagram: Oxygen tension regulates MSC plasticity through state fluctuations and HIF-1α signaling. Low oxygen increases state fluctuations and plasticity rates, while high oxygen promotes differentiation.

Under low oxygen conditions (1-5% O₂), MSCs exhibit enhanced proliferation, increased plasticity, and modified paracrine secretion, including increased miR-126 in exosomes [35]. Computational models predict that low oxygen promotes faster regeneration of population heterogeneity through increased state fluctuations [38]. This has practical implications for in vitro expansion, where physiological oxygen tension (2-5% O₂) better maintains stemness compared to atmospheric oxygen (20% O₂).

Extracellular Matrix and Mechanical Cues

ECM composition, stiffness, and topography provide critical biophysical signals that influence MSC immunomodulation through mechanotransduction pathways. Higher matrix rigidity promotes osteogenic differentiation through increased integrin signaling and actin cytoskeleton tension [35], while softer matrices maintain multipotency. The tissue origin of ECM matters—MSCs proliferate better when cultured on ECM derived from their native tissue [35].

Cellular Microenvironment

The immunomodulatory functions of MSCs are significantly shaped through interactions with immune cells in their microenvironment, creating bidirectional regulatory loops.

Macrophage Interactions

MSCs promote the polarization of macrophages from the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype through secretion of PGE2, TGF-β, and CCL2 [37]. In liver injury models, MSCs increase activity of the Hippo pathway, which activates NLRP3 and regulates XBP1-mediated NLRP3, leading to M2 differentiation [37]. Additionally, MSC-derived extracellular vesicles can reduce colitis in mice by inducing colonic macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype [37].

T-cell and B-cell Regulation

MSCs maintain macrophages and dendritic cells in an immature or anti-inflammatory state, preventing activation of effector T-cells and promoting regulatory T-cell (Treg) formation [37]. Human umbilical cord-derived MSCs specifically inhibit T lymphocyte proliferation, downregulate RORγt expression, reduce Th17 cells, and increase Treg populations in the spleen [37].

For B-cells, adipose tissue-derived MSCs inhibit plasma cell formation and promote regulatory B-cell (Breg) production [37]. These Breg cells produce IL-10, which transforms effector CD4+ T cells into Foxp3+ Tregs [37]. MSC-mediated suppression of B-cell proliferation occurs through induction of G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and secretion of Blimp-1, with intercellular communication mediated through PD-1 [37].

Experimental Approaches for Studying MSC-Microenvironment Interactions

In Vitro Modeling Protocols

Protocol 1: Cytokine Priming of MSCs for Enhanced Immunosuppression

Purpose: To pre-condition MSCs with inflammatory cytokines to enhance their immunosuppressive properties prior to therapeutic application.

Materials:

- Complete MSC culture medium (e.g., α-MEM with 10% FBS)

- Recombinant human IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β

- 6-well tissue culture plates

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS)

- Trypsin/EDTA for cell detachment

Procedure:

- Culture MSCs to 70-80% confluence in complete medium.

- Prepare cytokine cocktail containing 10-50 ng/mL IFN-γ + 10-20 ng/mL TNF-α in complete medium.

- Remove existing medium from MSC cultures and add cytokine-containing medium.

- Incubate for 24-48 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

- Wash cells with PBS and harvest using standard trypsinization.

- Validate priming efficacy through IDO activity assay or PD-L1 surface expression by flow cytometry.

Technical Notes: Optimal cytokine concentrations should be determined empirically for each MSC donor source. Avoid prolonged exposure (>72 hours) to prevent senescence induction.

Protocol 2: Hypoxic Conditioning of MSCs

Purpose: To mimic physiological oxygen conditions and enhance MSC stemness and paracrine function.

Materials:

- Hypoxia chamber or tri-gas incubator

- Oxygen sensors or indicators

- Serum-free MSC collection medium

Procedure:

- Culture MSCs to 60-70% confluence under standard conditions.

- Transfer cells to hypoxia chamber pre-equilibrated to 1-5% O₂, 5% CO₂, balance N₂.