Unveiling the Mechanisms: How MSC Exosomes Enter and Reprogram Keratinocytes and Endothelial Cells for Regenerative Therapy

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the cellular uptake mechanisms of Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC)-derived exosomes by keratinocytes and endothelial cells, two critical cell types in cutaneous wound healing...

Unveiling the Mechanisms: How MSC Exosomes Enter and Reprogram Keratinocytes and Endothelial Cells for Regenerative Therapy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the cellular uptake mechanisms of Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC)-derived exosomes by keratinocytes and endothelial cells, two critical cell types in cutaneous wound healing and vascular repair. We explore the foundational biology of exosome internalization, methodological approaches for tracking and enhancing uptake, strategies to overcome experimental and therapeutic bottlenecks, and comparative validation of exosomes from different MSC sources. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current evidence and technological advances to guide the rational design of more effective exosome-based nanotherapeutics for regenerative medicine.

The Cellular Gateway: Foundational Principles of MSC Exosome Uptake

Exosomes are nanoscale extracellular vesicles that play a critical role in intercellular communication through their specialized cargo. This technical guide provides a comprehensive examination of exosome biogenesis pathways, cargo sorting mechanisms, and compositional analysis. Framed within research on mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) exosome uptake by keratinocytes and endothelial cells, this review synthesizes current understanding of these sophisticated biological entities and their potential therapeutic applications in regenerative medicine.

Exosome Biogenesis: Cellular Production Pathways

Exosome biogenesis involves a meticulously orchestrated intracellular process that begins with endocytosis and culminates in extracellular release. These vesicles are defined by their endosomal origin and characteristic size range of 30-200 nanometers in diameter [1] [2]. The biogenesis pathway can be categorized into four distinct phases, each regulated by specific molecular machinery.

Early Endosome Formation

The biogenesis pathway initiates with the inward budding of the plasma membrane, forming early sorting endosomes [3] [4]. This process is regulated by specific protein complexes including:

- Clathrin-mediated endocytosis: Facilitates concentration of cargo into clathrin-coated pits [3]

- Caveolin-1 dependent pathways: Particularly important in caveolae generation and membrane invagination [3]

- Rab GTPase proteins: Especially Rab5a, which when knocked down decreases exosome excretion [3]

The formation of early endosomes can be influenced by tubular carriers containing MICAL-like protein 1 (MICAL-L1) and syndapin 2, a Bin/amphiphysin/Rvs (BAR) domain protein that inserts into the endosomal bilayer structure and bends the membrane [3].

Multivesicular Body Formation and Maturation

Early endosomes undergo significant transformation into late endosomes and subsequently into multivesicular bodies (MVBs) through a second inward budding process that creates intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within larger endosomal compartments [1] [3]. Two primary mechanisms regulate this critical step:

ESCRT-Dependent Pathway: The endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) comprises approximately 30 proteins organized into four distinct complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, and -III) along with associated proteins including VPS4 and Alix [1]. This machinery operates sequentially: ESCRT-0 recognizes and sorts ubiquitinated intracellular cargos; ESCRT-I and -II deform the membrane into buds with sequestered vesicles; and ESCRT-III facilitates vesicle scission [1].

ESCRT-Independent Pathways: Several alternative mechanisms can generate ILVs without ESCRT involvement:

- Tetraspanin-mediated pathways: Tetraspanins (CD63, CD9, CD37, CD82, CD81) participate in extracellular vesicle biogenesis and are essential for secretion and uptake [1]

- Lipid-dependent mechanisms: Neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2) contributes to ILV formation through lipid metabolism [3]

- Additional effectors: Flotillins and cholesterol also participate in the budding process [3]

MVB Fate Determination and Exosome Release

MVBs face one of two potential fates: degradation through fusion with lysosomes or autophagosomes, or release of exosomes through fusion with the plasma membrane [1] [3] [5]. The molecules responsible for MVB docking and fusion with the plasma membrane include:

- Rab GTPase proteins: Particularly Rab27, which regulates vesicle trafficking and membrane fusion [5]

- SNARE proteins: Facilitate membrane fusion events [2]

- Calcium channels and cellular pH: Modulate the exocytosis process [2]

This final fusion event releases the ILVs as exosomes into the extracellular space, where they can interact with recipient cells [1].

Table 1: Key Molecular Regulators of Exosome Biogenesis

| Biogenesis Stage | Regulatory Molecules | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Early Endosome Formation | Clathrin, Caveolin-1, Rab5a | Membrane invagination and vesicle formation |

| MVB Formation | ESCRT complexes (0, I, II, III), VPS4, Alix | Cargo sorting and ILV formation |

| ESCRT-Independent Formation | Tetraspanins (CD63, CD9, CD81), nSMase2 | Alternative biogenesis pathways |

| MVB Fate Determination | Rab GTPases (Rab27), SNARE proteins | Vesicle trafficking and membrane fusion |

Figure 1: Exosome Biogenesis Pathway. This diagram illustrates the sequential stages of exosome formation, from early endosome generation to eventual exosome release or degradation, highlighting key regulatory molecules at each step.

Exosome Cargo Composition and Sorting Mechanisms

Exosomes carry a diverse molecular payload that reflects their cellular origin and physiological state. This cargo is strategically sorted through specific mechanisms that ensure appropriate composition and function.

Molecular Constituents of Exosomes

Exosomes contain complex biomolecular arrays that can be categorized into several classes:

Protein Content:

- Transmembrane proteins: Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), MHC classes I and II, adhesion molecules [1] [2] [4]

- Cytosolic proteins: Heat shock proteins (HSP70, HSP90), transcription factors, enzymes (ATPase, phosphoglycerate kinase) [1] [2]

- Biogenesis-related proteins: ALIX, TSG101, ESCRT machinery components [2] [5]

- Cytokines and chemokines: Various signaling molecules [4]

Nucleic Acid Composition:

- RNA species: microRNA (miRNA), messenger RNA (mRNA), non-coding RNAs including circular and long noncoding RNAs [1] [2] [4]

- DNA components: Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), genomic DNA fragments [6] [5]

Lipid Profile: Exosomal membranes are enriched in specific lipids including sphingomyelin (SM), desaturated phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine (PS), desaturated phosphatidylcholine (PC), cholesterol (CHOL), GM3, and ganglioside [1]. This unique lipid composition contributes to membrane rigidity and stability while facilitating cellular uptake.

Cargo Sorting Mechanisms

The selective packaging of molecules into exosomes occurs through sophisticated sorting mechanisms:

ESCRT-Mediated Sorting: The ESCRT machinery not only facilitates ILV formation but also participates in cargo selection, particularly for ubiquitinated proteins [1] [3].

Tetraspanin-Organized Microdomains: Tetraspanins create specialized membrane platforms that recruit specific client proteins for incorporation into exosomes [1].

Lipid-Dependent Sorting: Ceramide and other lipids contribute to the formation of lipid rafts that facilitate the sorting of specific proteins into exosomes [1].

RNA-Binding Protein Coordination: RNA motifs and RNA-binding proteins (such as hnRNPs) mediate the selective packaging of RNA species into exosomes [4].

Table 2: Major Exosome Cargo Components and Their Functions

| Cargo Category | Specific Examples | Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Transmembrane Proteins | CD9, CD63, CD81, MHC-I/II | Vesicle identification, antigen presentation |

| Intracellular Proteins | HSP70, HSP90, ALIX, TSG101 | Stress response, biogenesis regulation |

| Nucleic Acids | miRNA, mRNA, circRNA, mtDNA | Genetic regulation, horizontal gene transfer |

| Lipids | Cholesterol, sphingomyelin, phosphatidylserine | Membrane stability, signaling, cellular uptake |

| Signaling Molecules | Cytokines, chemokines, growth factors | Intercellular communication, immune modulation |

Experimental Methodologies for Exosome Research

Isolation and Purification Techniques

Multiple approaches have been developed for exosome isolation, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Ultracentrifugation: Considered the gold standard technique, differential ultracentrifugation involves sequential separation based on size and density [7] [2] [4]. While it provides relatively high purity and requires minimal reagents, it is time-consuming, requires expensive instrumentation, and may cause damage to exosomes or co-isolate lipoproteins [2] [4].

Size-Based Techniques:

- Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC): Separates exosomes based on size differences, preserving integrity and bioactivity but potentially co-isolating similar-size vesicles [7]

- Tangential flow filtration (TFF): Uses parallel flow dynamics to reduce clogging potential, suitable for large-scale applications [2]

Polymer Precipitation: Utilizes hydrophilic polymers to force exosomes out of solution, offering ease of use but potential contamination with non-vesicular components [7].

Immunoaffinity Capture: Employs antibodies against exosome surface markers (CD9, CD63, CD81) for high-purity isolation, though it depends on surface antigen expression and may miss subpopulations [7] [2] [4].

Microfluidics-Derived Techniques: Emerging approaches that offer rapid processing with small sample volumes, though not yet widely established [7].

Combining multiple complementary methods often performs better in reducing contamination, improving separation purity, and maintaining natural exosome characteristics [7].

Characterization and Validation Methods

Comprehensive exosome characterization requires multi-parametric analysis:

Physical Characterization:

- Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA): Determines particle size distribution and concentration

- Dynamic light scattering (DLS): Measures size distribution of particles in suspension

- Transmission electron microscopy (TEM): Visualizes exosome morphology and structure

Biochemical Characterization:

- Western blotting: Detects specific protein markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, ALIX)

- Flow cytometry: Analyzes surface markers, though size limitations require special instrumentation

- Proteomic/lipidomic/genomic analysis: Comprehensive profiling of molecular cargo

Researchers should adhere to MISEV (Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles) guidelines to ensure reproducibility and quality in exosomal research [7].

MSC Exosome Uptake by Keratinocytes and Endothelial Cells

The therapeutic potential of MSC-derived exosomes is particularly relevant for skin regeneration and vascular repair, processes dependent on efficient uptake by keratinocytes and endothelial cells.

Uptake Mechanisms

Exosomes utilize multiple pathways to enter recipient cells, with preference depending on exosome characteristics and the target cell type:

Fusion: Direct merging with the plasma membrane, resulting in release of contents intracellularly, mediated by SNARE and Rab proteins [2].

Endocytosis:

- Clathrin-mediated endocytosis: A stepwise process involving clathrin-coated vesicle formation [3] [2]

- Caveolin-mediated endocytosis: Dependent on caveolin proteins, particularly caveolin-1 in epithelial cells [2]

- Lipid raft-mediated endocytosis: Utilizes sphingolipid- and cholesterol-enriched membrane microdomains [2]

- Macropinocytosis: Actin-driven process creating membrane extensions that internalize extracellular materials [2]

Phagocytosis: Primarily observed in professional phagocytes like macrophages, involving membrane deformation and phagosome formation [2].

Receptor-Mediated Interactions: Specific ligand-receptor interactions facilitate targeted binding and subsequent internalization [4].

Functional Consequences of Uptake

Upon internalization by keratinocytes and endothelial cells, MSC exosomes exert pleiotropic effects:

Keratinocyte Responses:

- Enhanced proliferation and migration: Critical for re-epithelialization during wound healing [6] [8]

- Modulation of differentiation: Influences keratinocyte maturation and barrier function

- Cytoprotection: Increased resistance to oxidative stress and apoptosis

Endothelial Cell Responses:

- Angiogenic stimulation: Promotes tube formation and vascular network development [6] [9]

- Barrier function enhancement: Improves endothelial integrity

- Proliferation and migration: Facilitates vascular repair and regeneration

The molecular mechanisms underlying these effects involve the delivery of regulatory miRNAs, proteins, and lipids that modulate key signaling pathways including PI3K/AKT, Wnt/β-catenin, and TGF-β/Smad [6].

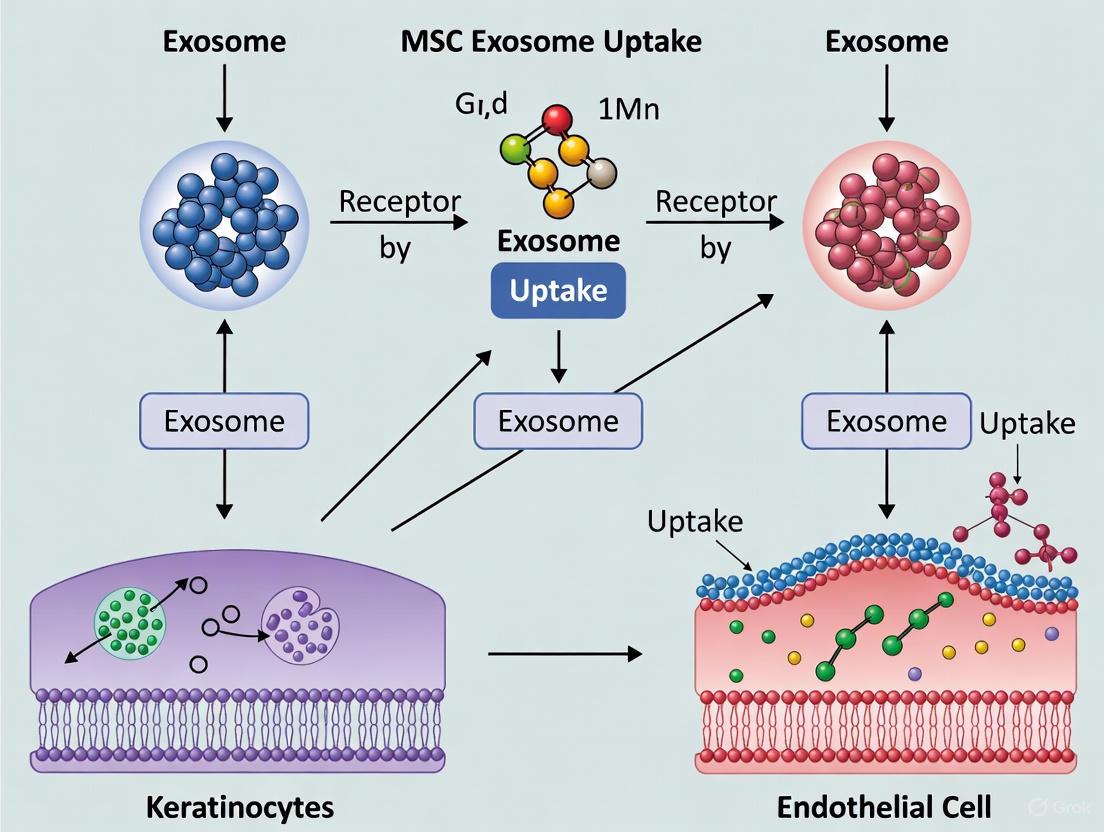

Figure 2: MSC Exosome Uptake Mechanisms and Functional Outcomes in Target Cells. This diagram illustrates the various pathways through which MSC-derived exosomes enter keratinocytes and endothelial cells, and the subsequent biological effects that promote tissue repair and regeneration.

Research Reagent Solutions for Exosome Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Exosome Isolation, Characterization, and Functional Analysis

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Polymer-based precipitation kits, Immunoaffinity columns (CD9/CD63/CD81) | Rapid exosome isolation from biological fluids | Potential co-precipitation of contaminants; antibody specificity critical |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, ALIX, HSP70 | Exosome validation by western blot, flow cytometry, immunofluorescence | Confirm specificity for species of interest; optimize concentration |

| Tracking Dyes | PKH67, PKH26, DiI, DiD, CFSE, GFP-labeled markers | Exosome labeling for uptake and trafficking studies | Potential dye aggregation; validate non-toxic concentrations |

| Cell Culture Supplements | Exosome-depleted FBS, defined growth factors | Production of exosomes in controlled conditions | Verify exosome depletion efficiency; maintain cell viability |

| Knockdown/CRISPR Tools | siRNA against Rab27a, nSMase2, ESCRT components; CRISPR for tetraspanins | Functional studies of biogenesis mechanisms | Confirm knockdown efficiency; monitor compensatory mechanisms |

| Analysis Kits | BCA protein assay, RNA extraction kits optimized for exosomes | Cargo quantification and analysis | Account for low RNA yields; use sensitive detection methods |

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol: MSC Exosome Uptake by Keratinocytes

Objective: Quantify and visualize internalization of MSC-derived exosomes by human keratinocytes.

Materials:

- MSC-derived exosomes isolated via ultracentrifugation or SEC

- Primary human keratinocytes

- Fluorescent membrane dyes (e.g., PKH67)

- Confocal microscopy equipment

- Flow cytometer with appropriate detectors

Procedure:

- Exosome Labeling:

- Resuspend exosome pellet (100 μg protein) in 1 mL Diluent C

- Add PKH67 ethanol dye solution (2 μM final concentration)

- Incubate 5 minutes at room temperature, protected from light

- Add equal volume of 1% BSA to stop staining reaction

- Isolate labeled exosomes by ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g, 70 minutes)

- Wash with PBS and repeat centrifugation to remove unincorporated dye

Uptake Assay:

- Plate keratinocytes in 24-well plates (5 × 10^4 cells/well) and culture until 70% confluent

- Add labeled exosomes (20 μg/mL) to cells and incubate for 0, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes

- For inhibition studies, pre-treat cells with endocytosis inhibitors:

- Chlorpromazine (10 μM, clathrin-mediated inhibition)

- Filipin (5 μg/mL, caveolae-mediated inhibition)

- Cytochalasin D (10 μM, macropinocytosis inhibition)

Analysis:

- Flow cytometry: Trypsinize cells, wash with PBS, and analyze fluorescence intensity (Ex/Em: 490/502 nm)

- Confocal microscopy: Fix cells with 4% PFA, stain actin with phalloidin-TRITC, mount with DAPI-containing medium, and image using appropriate filter sets

Protocol: Functional Angiogenesis Assay with Endothelial Cells

Objective: Assess pro-angiogenic effects of MSC exosomes on endothelial tube formation.

Materials:

- Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)

- Growth factor-reduced Matrigel

- MSC exosomes (0.35-1.75 μg/mL concentration range) [7]

- Tubule formation analysis software

Procedure:

- Matrigel Preparation:

- Thaw Matrigel overnight at 4°C

- Coat 96-well plates (50 μL/well) and polymerize at 37°C for 30 minutes

Tube Formation Assay:

- Serum-starve HUVECs for 4 hours

- Trypsinize, count, and resuspend cells in exosome-containing medium (2 × 10^4 cells/100 μL)

- Plate cells on Matrigel-coated plates

- Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for 4-8 hours

Quantification:

- Capture images using phase-contrast microscopy (4× objective)

- Analyze tube parameters: total tube length, number of branch points, number of meshes

- Compare experimental groups to positive (complete medium) and negative (serum-free) controls

Exosome biogenesis and cargo composition represent fundamental biological processes with significant implications for therapeutic development. The intricate molecular machinery governing exosome formation, cargo sorting, and cellular uptake provides multiple points for scientific investigation and potential intervention. MSC-derived exosomes offer particular promise as cell-free therapeutic agents, leveraging their natural trafficking capabilities to deliver complex molecular payloads to target cells like keratinocytes and endothelial cells. As research methodologies continue to advance, particularly in single-vesicle analysis and engineered exosome technologies, our understanding of these sophisticated nanoscale communicators will undoubtedly expand, opening new avenues for regenerative medicine and targeted therapeutic applications.

Exosomes, nanoscale extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm), are fundamental mediators of intercellular communication, transferring functional proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids between cells [10]. Their uptake by recipient cells is a critical step for eliciting biological effects and is of paramount importance for developing exosome-based therapeutic applications [11] [12]. In the context of regenerative medicine, understanding how mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes are internalized by specific target cells like keratinocytes and endothelial cells is a central research focus [13] [14]. These uptake processes are not random but are highly regulated by the exosome's cellular origin, surface composition, and the recipient cell's type and state [10] [12]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical overview of the universal mechanisms—membrane fusion, endocytosis, and receptor-mediated internalization—that govern exosome uptake, with a specific frame of reference for research involving MSC exosome interactions with keratinocytes and endothelial cells.

Major Exosome Uptake Pathways

Exosomes utilize a complex array of pathways to deliver their cargo into recipient cells. The primary mechanisms are membrane fusion, various forms of endocytosis, and phagocytosis, each leading to distinct intracellular fates for the vesicle and its cargo [10] [13] [12].

Table 1: Major Pathways of Exosome Uptake by Recipient Cells

| Uptake Mechanism | Key Molecular Regulators | Intracellular Fate | Implications for Cargo Delivery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane Fusion | SNARE proteins [11] | Direct release of cargo into cytoplasm | Avoids endolysosomal degradation; direct access to cytosolic targets |

| Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis | Clathrin, Dynamin, Chlorpromazine-sensitive pathways [15] [16] | Trafficking to early endosomes, then to lysosomes | Cargo can be degraded; requires escape from endosomes for bioactive delivery |

| Caveolae-Mediated Endocytosis | Caveolin-1, Dynamin, Nystatin-sensitive pathways [16] [13] | Trafficking to caveosomes | Bypasses classical endolysosomal pathway; alternative delivery route |

| Macropinocytosis | Actin, Na+/H+ exchangers, Amiloride-sensitive pathways [13] | Trafficking to macropinosomes, then to lysosomes | Non-specific uptake of extracellular fluid and vesicles; cargo subject to degradation |

| Phagocytosis | Actin cytoskeleton (primarily in phagocytes) [13] | Trafficking to phagolysosomes | Primarily in specialized cells; strong degradation environment |

| Clathrin-Independent Endocytosis | Galectin-3, Lysosome-associated membrane protein-2B (LAMP2B), Dynamin [16] | Recycling pathways [16] | Facilitated by paracrine adhesion signaling; may avoid degradation |

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression of these key uptake mechanisms and their intracellular trajectories.

Receptor-Mediated Internalization and Adhesion

The initial attachment of exosomes to the recipient cell plasma membrane is a critical, receptor-mediated step that often dictates the subsequent internalization pathway [11] [16]. This adhesion is far from a simple docking event; it can trigger active signaling within the recipient cell that facilitates the ultimate uptake of the vesicle.

Table 2: Key Molecules in Exosome Adhesion and Receptor-Mediated Internalization

| Adhesion Molecule Category | Specific Molecules on Exosome / Recipient Cell | Function in Uptake | Cell Type / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrins | αvβ3/β5, β1 (CD29), α3 (CD49c), αL (CD11a) [11] | Mediate firm adhesion; trigger intracellular signaling; determine organotropism [11] | Endothelial cells, Keratinocytes, Cancer cells |

| Tetraspanins | CD9, CD63, CD81, CD82 [11] | Form platforms that spatially organize receptors; influence signal induction [11] | Ubiquitous exosome markers; various cell types |

| Immunoglobulin Superfamily | ICAM-1 (on exosome) / LFA-1 (on cell) [11] | Critical for initial binding/docking, especially in immune contexts [11] | Dendritic cells, T cells |

| Lectin Families | Galectin-3 [16] | Binds glycoproteins; mediates clathrin-independent endocytosis [16] | Tumor cells, Endothelial cells |

| Other Adhesion Proteins | CD169 (sialoadhesin) on macrophages [11]; Heparin sulfate proteoglycans [11] | Capture and internalize exosomes [11] | Macrophages, Glioblastoma cells, Kidney cells |

| MHC & Antigen Presentation | MHC Class I & II with antigen [11] | Directs exosomes to antigen-specific T cells [11] | Antigen-presenting cells, T cells |

A pivotal finding is that the adhesion of paracrine exosomes (derived from different cells) to recipient cells can trigger intracellular Ca2+ mobilization via activation of Src family kinases and phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ). This Ca2+ signal subsequently activates the calcineurin–dynamin machinery, which directly promotes exosome internalization, often routing them into recycling pathways [16]. This indicates that the recipient cell is an active participant in the uptake process, not a passive vessel.

Experimental Protocols for Studying Uptake

Elucidating the specific pathway used in a given biological context requires carefully designed experiments involving chemical inhibition, genetic manipulation, and advanced imaging.

Pharmacological Inhibition of Specific Pathways

A standard methodology to dissect the contribution of different endocytic routes is the use of specific pharmacological inhibitors [15].

Protocol: Inhibitor-Based Pathway Analysis

- Cell Seeding: Plate recipient cells (e.g., keratinocytes or endothelial cells) in multi-well plates or on glass coverslips and allow them to adhere and grow to ~70% confluency.

- Inhibitor Pre-treatment: Incubate cells with optimized concentrations of pathway-specific inhibitors in serum-free media for 30 minutes to 1 hour prior to exosome addition. Common inhibitors include:

- Exosome Incubation: Add fluorescently labeled exosomes (e.g., DiO, DiD, PKH67) to the pre-treated cells. Incubate for a defined period (e.g., 1-4 hours) at 37°C.

- Wash and Analysis: Thoroughly wash cells with PBS to remove non-internalized exosomes. Analyze internalization using:

- Imaging Flow Cytometry: Provides quantitative, high-throughput data on the percentage of cells with internalized exosomes and the fluorescence intensity per cell [15].

- Confocal Microscopy: Allows visual confirmation of intracellular localization of exosomes, typically appearing as punctate dots within the cell cytoplasm, and can be used to perform Z-stack analysis to confirm internalization versus surface binding [15].

Single-Particle Tracking and Super-Resolution Imaging

To overcome the limitations of bulk population assays and directly observe the behavior of individual exosomes, state-of-the-art imaging techniques are employed.

Protocol: Single-SEV Particle Tracking [16]

- Exosome Labeling: Label exosomes with lipophilic dyes (e.g., DiO) or genetically engineer donor cells to express tetraspanins (CD63, CD9, CD81) fused with fluorescent proteins (e.g., mGFP, Halo7-tag).

- Image Acquisition: Use high-speed, high-sensitivity microscopy such as Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence Microscopy (TIRFM) or single-particle tracking setups to visualize individual exosome particles in living cells.

- Simultaneous Imaging: Combine single-particle tracking of exosomes with Photoactivated Localization Microscopy (PALM) to simultaneously observe membrane invaginations and other structural changes in the recipient cell's plasma membrane with super-resolution.

- Data Analysis: Analyze trajectories to determine the kinetics of binding, mode of entry (e.g., confined diffusion before internalization), and co-localization with markers of specific pathways (e.g., clathrin, caveolin).

Signaling Pathways in Exosome Uptake

The internalization of exosomes is not merely a mechanical process but can be regulated by, and in turn regulate, specific intracellular signaling cascades. Research in the context of MSC exosomes and their target cells has highlighted several key pathways.

Table 3: Key Signaling Pathways in Exosome Uptake and Function

| Signaling Pathway | Role in Uptake / Subsequent Function | Cell Type / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Src / PLCγ / Ca²⁺ Signaling | Paracrine exosome binding triggers Ca²⁺ mobilization, activating calcineurin and dynamin to drive internalization [16]. | Recipient cells (e.g., endothelial cells) |

| Wnt/β-catenin | MSC exosomes can deliver Wnt4, activating this pathway in recipient cells to promote proliferation and migration [17]. | Keratinocytes, Endothelial cells |

| MAPK Signaling | Uptake of MSC exosomes can modulate p38 MAPK and ERK pathways, influencing inflammatory responses and cell survival [17]. | Chondrocytes, Macrophages |

| Oxidative Stress (NRF2) | MSC exosomes reduce oxidative stress in recipient cells, a key mechanism in their regenerative effects [17]. | Keratinocytes, Neuronal cells |

The following diagram summarizes the key signaling pathway triggered by paracrine exosome adhesion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Successful investigation of exosome uptake mechanisms relies on a suite of essential reagents and tools.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Exosome Uptake Research

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Labels | DiO, DiD, PKH67, PKH26, CellTracker CM-Dil [15] | Label exosome membranes for visualization and tracking by flow cytometry and microscopy. |

| Pharmacological Inhibitors | Chlorpromazine, Nystatin, Bafilomycin A1, Amiloride, Dynasore [15] | Selectively block specific endocytic pathways to determine their contribution to uptake. |

| Genetic Tools | siRNAs/shRNAs (e.g., against clathrin, caveolin, dynamin); Plasmid vectors for fluorescent protein-tagged tetraspanins (CD63-GFP) [16] | Knock down or visualize components of the uptake machinery to study their role. |

| Antibodies for Staining | Anti-CD63, Anti-CD9, Anti-CD81, Anti-TSG101, Anti-Alix [14] | Characterize exosomes and confirm their identity via Western Blot, ELISA, or immunostaining. |

| Advanced Microscopy Systems | Imaging Flow Cytometry [15], Confocal Microscopy, TIRF Microscopy, dSTORM/PALM Super-Resolution Microscopy [16] | Visualize, quantify, and track exosome uptake at both population and single-particle levels. |

The universal mechanisms of exosome uptake—membrane fusion, endocytosis, and receptor-mediated internalization—are complex, dynamic, and context-dependent. For researchers focusing on MSC exosome interactions with keratinocytes and endothelial cells, the key takeaways are that uptake is an active process heavily influenced by surface adhesion molecules like integrins and tetraspanins, and that it can trigger specific signaling cascades within the recipient cell. The choice of experimental methodology, from pharmacological inhibition to sophisticated single-particle tracking, is critical for accurately delineating these pathways. A deep understanding of these mechanisms is the foundation for rationally designing engineered exosomes with enhanced targeting and delivery efficiency for therapeutic applications in wound healing, vascular regeneration, and beyond.

Keratinocyte-Specific Uptake Pathways and Post-Uptake Signaling Activation (e.g., PI3K/Akt, ERK)

Keratinocytes, the predominant cell type in the epidermis, rely on sophisticated intracellular signaling networks to regulate their core functions: proliferation, differentiation, migration, and programmed cell death. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) and mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK) pathways represent two crucial signaling axes that determine keratinocyte fate in both physiological and pathological contexts. These pathways integrate signals from the extracellular environment—including those from mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos)—to coordinate appropriate cellular responses during processes such as wound healing and epidermal homeostasis [18] [19] [20].

The PI3K/Akt pathway functions as a critical regulator balancing keratinocyte differentiation against apoptotic death, while the MAPK/ERK pathway primarily directs proliferative responses and capillary morphogenesis. Understanding the precise mechanisms through which these pathways are activated following the uptake of external cues, such as extracellular vesicles, provides fundamental insights for developing novel therapeutic strategies in regenerative medicine and dermatological disorders [21] [19] [20]. This technical guide examines the molecular machinery governing keratinocyte-specific uptake pathways and the subsequent signaling activation, with particular emphasis on their relevance to MSC exosome research.

PI3K/Akt Signaling in Keratinocytes

Pathway Mechanism and Regulation

The PI3K/Akt pathway serves as a central signaling node that determines the fate choice between keratinocyte differentiation and death. This pathway is activated during early stages of keratinocyte differentiation both in vitro and in intact epidermis in vivo [19]. Pathway activation initiates when extracellular signals stimulate receptor tyrosine kinases such as the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and Src families, leading to PI3K recruitment and conversion of phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) at the plasma membrane [18] [19].

Akt (protein kinase B) is then recruited to the membrane through its pleckstrin homology domain, where it undergoes phosphorylation and activation. Importantly, research demonstrates that PI3K/Akt activation in keratinocyte differentiation depends on E-cadherin-mediated adhesion, with PI3K increasingly associating with cadherin-catenin protein complexes bearing tyrosine-phosphorylated YXXM motifs during this process [19]. This membrane-proximal signaling complex integrates adhesion signals with growth factor signaling to fine-tune keratinocyte responses.

Functional Consequences of Pathway Activation

PI3K/Akt signaling promotes keratinocyte growth arrest and differentiation while protecting against premature apoptosis during this transition. Experimental evidence confirms that expression of active Akt in keratinocytes directly promotes growth arrest and differentiation, whereas pharmacological blockade of PI3K inhibits expression of late differentiation markers and leads to death of cells that would otherwise differentiate [19]. This pathway therefore represents a critical survival signal during keratinocyte differentiation, ensuring that cells complete their differentiation program rather than undergoing apoptotic death.

The functional outcomes of PI3K/Akt activation extend to wound healing contexts, where keratinocyte migration and re-epithelialization are essential. Keratinocyte-derived extracellular vesicles contain proteins that influence these processes, including integrins, growth factors, and matrix metalloproteinases that interact with PI3K/Akt signaling outputs [20].

Experimental Modulation and Assessment

Investigating PI3K/Akt signaling in keratinocytes requires specific methodological approaches, as outlined in Table 1. These include pharmacological inhibitors, genetic manipulation techniques, and assessment methodologies for evaluating pathway activity and functional outcomes.

Table 1: Experimental Approaches for Studying PI3K/Akt Signaling in Keratinocytes

| Method Category | Specific Approach | Key Reagents/Tools | Output Measurements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological Inhibition | PI3K pathway blockade | LY294002, Wortmannin | Differentiation marker expression, apoptosis assays |

| Genetic Manipulation | Constitutive activation | Active Akt constructs | Growth arrest, differentiation markers |

| Pathway Assessment | Phosphorylation status | Phospho-specific Akt antibodies (Ser473, Thr308) | Western blot, immunofluorescence |

| Functional Assays | Differentiation capacity | Calcium-induced differentiation model | Late differentiation markers (involucrin, loricrin) |

| Adhesion Studies | E-cadherin engagement | Calcium switch assays | Co-immunoprecipitation of cadherin-catenin complexes |

MAPK/ERK Signaling in Keratinocytes

Pathway Mechanism and Regulation

The MAPK/ERK pathway represents another crucial signaling cascade in keratinocytes, particularly in contexts of angiogenesis and wound healing. This pathway is activated in response to various stimuli, including growth factors, cytokines, and physical cues such as electric fields (EF) [21]. The canonical RAF-MEK-ERK phosphorylation cascade begins with RAS activation, progressing through sequential phosphorylation of RAF, MEK, and ultimately ERK, which then translocates to the nucleus to regulate gene expression.

In microvascular endothelial cells, which share signaling similarities with keratinocytes during wound responses, EF exposure has been shown to enhance capillary morphogenesis and promote MEK-cRaf complex formation along with subsequent MEK and ERK phosphorylation [21]. This activation occurs in a frequency-dependent manner, with high-frequency EF (7.5 GHz) proving more effective than low-frequency (60 Hz) stimulation. Importantly, EF-induced MEK phosphorylation can be reversed by MEK and Ca²⁺ inhibitors, reduced by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) inhibition, and operates independently of PI3K pathway activation [21].

Functional Consequences of Pathway Activation

MAPK/ERK signaling drives keratinocyte functions essential for wound healing, including proliferation, migration, and the secretion of factors that support angiogenesis. Activation of this pathway enhances vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) release, a key angiogenic factor that promotes neovascularization in healing tissues [21]. The ERK pathway also influences keratinocyte interactions with other cell types, including fibroblasts and immune cells, through regulation of cytokine and chemokine production.

Notably, the endothelial response to EF that activates MAPK/ERK does not require VEGF binding to its receptor VEGFR2, indicating that this pathway can be initiated through alternative mechanisms relevant to tissue regeneration strategies [21]. This finding has significant implications for understanding how physical stimulation approaches might enhance healing in compromised wound environments.

Experimental Modulation and Assessment

Research into MAPK/ERK signaling employs distinct methodological approaches, particularly when investigating responses to physical stimuli like electric fields. Table 2 outlines key experimental parameters and assessment methods for studying this pathway.

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for MAPK/ERK Signaling Investigation

| Parameter | High-Frequency EF | Low-Frequency EF | Assessment Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 7.5 GHz | 60 Hz | Phospho-ERK/MEK immunoblotting |

| Field Intensity | 156 mV/mm | 209 mV/mm | Capillary morphogenesis assays |

| Setup | Cavity resonator | Parallel-plate capacitor | VEGF measurement (ELISA) |

| Key Inhibitors | MEK inhibitors (U0126), Ca²⁺ inhibitors | MEK inhibitors, eNOS inhibitors | Raf-MEK co-immunoprecipitation |

| Biological Effects | Enhanced capillary formation, VEGF release | Reduced response | Cell proliferation/migration assays |

Extracellular Vesicle Uptake and Signaling Activation

Keratinocyte-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

Keratinocytes actively secrete extracellular vesicles (EVs), including exosomes and microvesicles, that carry diverse molecular cargo capable of influencing recipient cell behavior. Keratinocyte-derived EVs contain characteristic membrane proteins (ITGA6, CD9, CD63) and cytoplasmic proteins (HSPA5, eEF1A1, SDCBP) that facilitate skin development and repair [20]. These EVs also carry specialized proteins including transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), epidermal growth factor (EGF), involucrin, kallikrein 7 (KLK7), jagged 1 (JAG1), plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1), and multiple matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1, -3, -8, -9) that collectively influence wound re-epithelialization, extracellular matrix remodeling, and cellular adhesion/migration [20].

The biological state of keratinocytes determines EV composition, with differentiated versus undifferentiated keratinocytes releasing distinct exosomal populations containing different isoforms of 14-3-3 proteins [20]. Similarly, activated migrating keratinocytes secrete EVs containing cathepsin B, which participates in intracellular proteolysis during wound healing. This state-dependent variation in EV content represents a mechanism for fine-tuning cellular responses during tissue repair.

MSC Exosomes as Signaling Modulators

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) have emerged as powerful acellular therapeutic tools that can modify regenerative programs in recipient cells, including keratinocytes, by delivering functional RNAs, proteins, and other signaling elements [22] [6]. These nanoscale vesicles precisely regulate inflammatory responses, angiogenesis, and tissue repair processes by targeting central signaling pathways in keratinocytes, including PI3K/Akt, JAK/STAT, TGF-β/Smad, and Wnt/β-catenin cascades [6].

MSC-Exos offer significant advantages over whole-cell therapies, including low immunogenicity, efficient biological barrier penetration, stable storage characteristics, and reduced risks of tumorigenicity [22]. Their capacity to regulate macrophage activation, stimulate angiogenesis, and promote keratinocyte and dermal fibroblast proliferation and migration makes them particularly valuable for dermatological applications and wound healing [6]. Worldwide, 64 registered clinical trials have preliminarily validated the safety and applicability of MSC-EVs across various diseases, showing significant progress in treating complex wound healing, among other conditions [22].

Integration of Signaling Pathways in Keratinocyte Functions

Cross-Talk Between PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK Pathways

While often studied separately, the PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK pathways exhibit significant cross-talk in keratinocytes, creating a signaling network that integrates multiple inputs to determine cellular responses. Both pathways can be simultaneously activated by common upstream signals, including receptor tyrosine kinase engagement and integrin-mediated adhesion events. The balanced activation of these pathways likely determines whether keratinocytes primarily undergo differentiation (favored by PI3K/Akt) versus proliferation (favored by MAPK/ERK).

This cross-talk becomes particularly relevant in the context of MSC exosome therapy, as these vesicles deliver complex cargo that may simultaneously modulate multiple signaling pathways. Understanding the integrated response of these pathways to exosomal components is essential for predicting and optimizing therapeutic outcomes in regenerative applications.

Therapeutic Implications for Skin Disorders and Wound Healing

The strategic manipulation of keratinocyte signaling pathways holds significant promise for treating various dermatological conditions and enhancing wound healing. Dysregulated PI3K/Akt signaling contributes to pathological conditions such as psoriasis, while proper activation of this pathway supports keratinocyte differentiation and barrier formation [23]. Similarly, controlled MAPK/ERK activation promotes the re-epithelialization crucial for healing chronic wounds, including those in diabetic patients [21] [24].

MSC exosomes represent a promising vehicle for delivering targeted modulation of these pathways, as they can be engineered to enrich specific miRNA or protein cargo that preferentially activates desired signaling outcomes. Current research focuses on enhancing exosome targeting, optimizing production processes, and understanding long-term biodistribution to facilitate clinical translation of these approaches [22].

Visualization of Signaling Pathways

Keratinocyte Signaling Pathway Diagram

Diagram Title: Keratinocyte Signaling Pathways Integration

This diagram illustrates the integrated signaling network in keratinocytes, highlighting how external stimuli including MSC exosomes, electric fields, growth factors, and cell adhesion events converge on the PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK pathways. The visualization emphasizes key activation steps and demonstrates potential cross-talk between these crucial signaling axes that determine keratinocyte fate decisions.

Experimental Workflow for Signaling Studies

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Signaling Studies

This workflow outlines a systematic approach for investigating keratinocyte signaling pathways, from initial cell culture through treatment application, molecular analysis, functional assessment, and final data integration. The methodology supports comprehensive evaluation of how MSC exosomes and other stimuli modulate PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK signaling networks.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Keratinocyte Signaling Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PI3K/Akt Inhibitors | LY294002, Wortmannin | Selective PI3K inhibition | Confirm specificity via downstream phosphorylation |

| Akt Activators | SC79 | Allosteric Akt activation | Validate with phosphorylation-specific antibodies |

| MAPK Pathway Inhibitors | U0126 (MEK inhibitor) | Blocks ERK phosphorylation | Use appropriate concentrations to avoid off-target effects |

| Calcium Modulators | BAPTA-AM, Thapsigargin | Modulate intracellular Ca²⁺ | Essential for EF studies and adhesion signaling |

| eNOS Inhibitors | L-NAME | Reduces nitric oxide production | Important for mechanotransduction studies |

| Keratinocyte Culture Models | Primary keratinocytes, HaCaT cells | Physiological relevance vs. immortalized line | Primary cells better reflect in vivo differentiation |

| EV Isolation Tools | Ultracentrifugation, Size-exclusion chromatography, Immunoprecipitation | Isolation of keratinocyte or MSC-derived EVs | Method affects yield, purity, and biological activity |

| Differentiation Inducers | High-calcium medium | Induces keratinocyte differentiation | Essential for studying differentiation-linked signaling |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Anti-pAkt (Ser473, Thr308), Anti-pERK, Anti-pMEK | Detection of pathway activation | Validate with appropriate controls and inhibition |

| Adhesion Molecules | Recombinant E-cadherin, Anti-E-cadherin antibodies | Study adhesion-mediated signaling | Critical for investigating mechanotransduction pathways |

Keratinocyte PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK signaling pathways represent sophisticated regulatory networks that integrate diverse external cues to determine cellular fate decisions. The PI3K/Akt pathway critically balances differentiation versus apoptotic death, while MAPK/ERK signaling directs proliferative and migratory responses essential for tissue repair. These pathways can be activated through multiple mechanisms, including MSC exosome uptake, electric field exposure, growth factor receptor engagement, and adhesion-mediated signaling.

Understanding the precise molecular mechanisms governing these pathways provides a foundation for developing targeted therapeutic strategies in regenerative medicine and dermatology. MSC exosomes represent particularly promising delivery vehicles for modulating these pathways, offering natural targeting capabilities, low immunogenicity, and complex cargo that can simultaneously engage multiple signaling nodes. Future research focusing on exosome engineering, pathway cross-talk, and in vivo validation will further enhance our ability to harness these signaling networks for therapeutic benefit.

Endothelial Cell Uptake Dynamics and Induction of Pro-angiogenic Responses

The uptake of mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-derived exosomes by endothelial cells represents a crucial mechanistic pathway in therapeutic angiogenesis. As natural nanoscale vesicles, exosomes facilitate intercellular communication by transferring bioactive cargo—including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—from donor MSCs to recipient endothelial cells, initiating a cascade of pro-angiogenic responses [25] [4]. This process is particularly relevant in the context of wound healing and tissue regeneration, where the formation of new blood vessels is essential for restoring oxygen and nutrient supply to damaged tissues [25] [8]. Understanding the precise dynamics of exosome uptake and the subsequent intracellular signaling events in endothelial cells provides a foundation for developing novel therapeutic strategies for conditions characterized by impaired angiogenesis, such as diabetic wounds, ischemic diseases, and other vascular insufficiencies [26] [27].

Mechanisms of Exosome Uptake by Endothelial Cells

The process of exosome internalization by endothelial cells is a coordinated sequence of events that leads to the delivery of exosomal cargo and the initiation of downstream signaling pathways. The journey begins with the initial contact and docking, where exosomes present surface molecules that interact with recipient endothelial cells [4]. Key surface proteins involved in this recognition include tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), integrins, and other adhesion molecules that facilitate binding to the endothelial cell membrane [20] [4].

Following initial contact, exosomes enter endothelial cells through multiple endocytic pathways. The predominant mechanism involves endocytosis, where the exosomes are engulfed through membrane invagination to form early sorting endosomes [4]. These early endosomes then mature into late sorting endosomes and subsequently form multivesicular bodies (MVBs) after a second indentation [4]. The final critical step involves the release of exosomal contents into the endothelial cell cytoplasm through the fusion of MVBs with the cell membrane or through direct membrane fusion, allowing the bioactive cargo to access intracellular compartments and modulate cellular functions [4].

The entire lifecycle from exosome biogenesis to uptake and intracellular signaling can be tracked using fluorescent, luminescent, and radioactive techniques, providing researchers with tools to visualize and quantify these dynamic processes [4].

Diagram 1: Endothelial cell exosome uptake and signaling pathway. This diagram illustrates the sequential process from MSC exosome release through cellular uptake mechanisms to final pro-angiogenic activation in endothelial cells.

Pro-angiogenic Responses in Endothelial Cells

Upon successful internalization and cargo release, MSC-derived exosomes initiate comprehensive pro-angiogenic programming in endothelial cells. This multifaceted response encompasses several critical processes that collectively contribute to new blood vessel formation.

Enhancement of Endothelial Cell Migration and Proliferation

The fundamental processes of endothelial cell migration and proliferation are significantly enhanced by exosomal exposure. Research has demonstrated that exosomes stimulate endothelial cell migration, inducing coverage of scratched surface areas up to 110 ± 31% compared to 47 ± 13% in negative controls based on scratch test assays [25]. This enhanced migratory capacity is essential for the initial stages of angiogenesis, allowing endothelial cells to navigate toward angiogenic stimuli. Simultaneously, exosomes promote endothelial cell proliferation through the delivery of growth factors and regulatory miRNAs that stimulate cell cycle progression and mitogenic signaling pathways [25] [27].

Induction of Tube Formation and Vascular Network Assembly

The most functionally significant outcome of exosome-mediated pro-angiogenic activation is the induction of capillary-like tube formation. In vitro tube formation assays using "ECM Gel Matrix" have quantified this effect, demonstrating that exosomes generate tube-like structures with complexity similar to VEGF-positive controls [25]. The pro-angiogenic effect is quantified through multiple parameters, including the number of junctions and meshes, as well as total tube length, all of which show significant enhancement following exosome treatment [25]. This structured assembly into tubular networks represents the culmination of the angiogenic process, resulting in the creation of new vascular structures capable of supporting blood flow.

Molecular Signaling Pathways Activated by Exosomal Cargo

The pro-angiogenic effects of MSC-derived exosomes are mediated through the activation of key molecular signaling pathways within endothelial cells. The VEGF-VEGFR signaling axis serves as a central regulator of this process [28]. When vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs) are activated, they recruit PI3K, initiating the PI3K/Akt pathway which directs cell growth, survival, and migration [28]. Simultaneously, VEGFR stimulation activates the MAPK cascade, including ERK, which is essential for endothelial cell proliferation and movement [28]. VEGFR signaling also upregulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), both of which support vascular growth, cell motility, and new vessel formation [28].

Table 1: Quantitative Pro-angiogenic Effects of MSC-Derived Exosomes on Endothelial Cells

| Angiogenic Parameter | Experimental Results | Experimental Method | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Migration | 110 ± 31% surface coverage | Scratch wound assay | Enhanced capacity for endothelial cell movement toward angiogenic stimuli |

| Tube Formation | Increased junctions, meshes, and total tube length | ECM Gel Matrix tube formation assay | Promotion of capillary-like structure assembly |

| Comparative Angiogenic Potential | Similar to VEGF-positive control | Comparative assay with VEGF control | Demonstration of potent pro-angiogenic activity |

Experimental Protocols for Studying Uptake and Angiogenic Responses

Exosome Isolation and Characterization

The investigation of endothelial cell uptake dynamics and pro-angiogenic responses requires standardized methodologies for exosome isolation and characterization. The current gold standard for exosome extraction is ultracentrifugation, which involves sequential centrifugation steps to separate exosomes from other extracellular vesicles and contaminants [4]. For enhanced purity, immunoaffinity chromatography utilizing antibodies against exosomal surface markers (CD9, CD63, CD81) provides high specificity, though it requires known surface antigen expression [4]. Additional techniques include size-exclusion chromatography and precipitation-based methods, each with distinct advantages and limitations in terms of yield, purity, and scalability [4].

Comprehensive characterization of isolated exosomes should include:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis: To determine size distribution and concentration, typically showing exosomes in the 30-150 nm range [25] [4]

- Transmission Electron Microscopy: To confirm cup-shaped morphology characteristic of exosomes [25]

- Western Blot Analysis: To detect exosomal markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, Alix) and exclude contaminants such as calnexin from endoplasmic reticulum membranes [25] [29]

- Flow Cytometry: To verify surface markers and quantify specific antigen presence [25]

Tracking Exosome Uptake Dynamics

Visualizing and quantifying exosome internalization by endothelial cells is essential for establishing uptake dynamics. Fluorescent labeling using lipophilic dyes such as PKH67 provides a robust method for tracking exosomes over time [25]. Following incubation with labeled exosomes, endothelial cells are fixed at predetermined time points and analyzed using confocal microscopy to determine the efficiency and kinetics of uptake. Additionally, techniques such as fluorescence anisotropy and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy can provide quantitative data on exosome-binding interactions [29].

Functional Angiogenesis Assays

The functional consequences of exosome uptake are evaluated through a series of standardized angiogenesis assays:

- Tube Formation Assay: Endothelial cells are seeded on "ECM Gel Matrix" and monitored for their ability to form capillary-like structures. Key parameters include the number of junctions, number of meshes, and total tube length, which are quantified using image analysis software [25]

- Scratch Wound Migration Assay: A standardized scratch is created in a confluent endothelial cell monolayer, and cell migration to close the wound is measured over 12-24 hours with and without exosome treatment [25]

- Proliferation Assays: Endothelial cell proliferation in response to exosome treatment is quantified using metabolic activity assays (e.g., MTT, CCK-8) or by directly counting cell numbers over time [25]

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for exosome uptake and angiogenesis studies. This diagram outlines the sequential methodology from initial exosome isolation through characterization and functional assessment of pro-angiogenic effects.

Research Reagent Solutions for Angiogenesis Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Exosome-Mediated Angiogenesis

| Research Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exosome Isolation Tools | Ultracentrifugation, Immunoaffinity (CD9/CD63/CD81), Size-exclusion chromatography | Exosome purification | Separation of exosomes from conditioned media or biological fluids based on physical properties or surface markers |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD9, Anti-CD63, Anti-CD81, Anti-TSG101, Anti-Alix, Anti-calnexin (negative) | Exosome validation | Confirmation of exosomal identity and purity through Western blot, flow cytometry, or immunofluorescence |

| Tracking Dyes | PKH67, PKH26, other lipophilic dyes | Uptake visualization | Fluorescent labeling of exosome membranes to track internalization by endothelial cells over time |

| ECM Matrices | ECM Gel Matrix, Matrigel | Tube formation assay | Providing a basement membrane substitute that supports endothelial cell organization into capillary-like structures |

| Angiogenesis Assay Kits | Tube formation assay kits, Migration assay kits | Functional assessment | Standardized systems for quantifying pro-angiogenic responses of endothelial cells following exosome treatment |

| Endothelial Cell Markers | CD31, VE-cadherin, vWF | Cell type validation | Confirmation of endothelial cell identity and assessment of phenotypic changes during angiogenesis |

The uptake dynamics of MSC-derived exosomes by endothelial cells and the subsequent induction of pro-angiogenic responses represent a sophisticated biological process with significant therapeutic implications. The molecular mechanisms involve precise exosome-receptor interactions, efficient internalization, and activation of key signaling pathways including VEGF-VEGFR, PI3K/Akt, and MAPK cascades [28]. The functional outcomes—enhanced migration, proliferation, and tube formation—collectively contribute to the formation of new vascular networks essential for tissue repair and regeneration [25]. As research in this field advances, the potential for harnessing these mechanisms for therapeutic angiogenesis in conditions characterized by vascular insufficiency continues to grow, offering promising avenues for the development of novel treatments for wound healing, ischemic diseases, and other vascular disorders.

Key Exosomal Cargo (miRNAs, Proteins) Implicated in Functional Modulation of Recipient Cells

Exosomes, nanoscale extracellular vesicles secreted by nearly all cell types, have emerged as pivotal mediators of intercellular communication, fundamentally advancing our understanding of cellular crosstalk in tissue homeostasis and repair. These lipid-bilayer enclosed vesicles transport a sophisticated cargo of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids from donor to recipient cells, thereby modulating recipient cell function and phenotype [30] [4]. Within the context of skin biology and the specific research focus on MSC exosome uptake mechanisms by keratinocytes and endothelial cells, exosomal cargo orchestrates critical wound healing processes including keratinocyte migration, angiogenesis, and inflammatory modulation [9] [31]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of the key functional cargos, with a particular emphasis on microRNAs (miRNAs), their quantitative profiles, mechanisms of action, and the experimental methodologies essential for elucidating their role in recipient cell modulation.

Exosomal Cargo: Composition and Functional Significance

Exosomes encapsulate a diverse array of biomolecules that reflect the physiological state of their parental cells and confer functional specificity. The cargo includes conserved tetraspanin proteins (CD9, CD63, CD81), heat shock proteins (HSP70, HSP90), biogenesis-related proteins (ALIX, TSG101), and major histocompatibility complexes, which serve as canonical exosomal markers [32] [4]. Beyond these structural components, the functionally active cargo includes:

- Nucleic Acids: DNA, mRNAs, microRNAs (miRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) that can regulate gene expression in target cells [30] [32].

- Proteins: Growth factors (VEGF, TGF-β, EGF), cytokines, and enzymes that directly activate signaling pathways [30].

- Lipids: Ceramide, sphingomyelin, phosphatidylserine, and cholesterol that contribute to membrane stability and biological activity [30].

The molecular composition of exosomes varies significantly based on cellular origin and extracellular environment. For instance, exosomes from three-dimensional dermal papilla spheroids contain elevated pro-hair growth miRNAs compared to those from 2D monolayers, while serum exosomes from psoriasis patients show elevated miR-199a-3p correlated with disease severity [30]. This compositional plasticity enables exosomes to perform context-specific functions, making them particularly valuable as therapeutic agents and diagnostic biomarkers.

Key Exosomal miRNAs and Their Functional Roles

MicroRNAs represent one of the most extensively studied and functionally significant exosomal cargo components. These small non-coding RNAs typically regulate gene expression by binding to target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or mRNA degradation. The table below summarizes key exosomal miRNAs implicated in skin repair and their specific effects on keratinocytes and endothelial cells.

Table 1: Key Exosomal miRNAs in Skin Repair and Recipient Cell Modulation

| miRNA | Exosome Source | Target Cells | Molecular Targets/Pathways | Functional Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-27b | Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells (HUMSCs) | Keratinocytes, Fibroblasts | ITCH/JUNB/IRE1α signaling | Activates keratinocytes and fibroblasts in vitro, accelerates wound healing in vivo | [30] |

| miR-181c | HUMSCs | Immune cells, Endothelial cells | TLR4/NF-κB pathway | Reduces inflammatory cytokine production | [30] |

| miR-21-3p | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Endothelial cells, Fibroblasts | PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 signaling | Promotes angiogenesis and enhances fibroblast function | [30] [33] |

| miR-223 | Bone Marrow MSCs (BMSCs) | Macrophages | Undefined | Promotes M2 polarization of macrophages | [30] |

| miR-146a | Adipose-derived MSCs (ADMSCs) | Endothelial cells | Src kinase | Mitigates endothelial cell senescence, promotes angiogenesis in diabetic models | [30] |

| miR-135a | Human Amnion MSCs | Keratinocytes, Fibroblasts | LATS2 (Hippo pathway kinase) | Inhibits LATS2, activates YAP/TAZ signaling, enhances keratinocyte migration and proliferation | [31] |

| miR-126 | Mesenchymal Stem Cells | Keratinocytes, Endothelial cells | PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways | Promotes epithelial cell survival and proliferation, enhances angiogenesis | [31] |

| miR-4505 | Keratinocytes (VDR-deficient) | Macrophages | Undefined | Promotes macrophage proliferation and M1 polarization (psoriasis pathogenesis) | [32] |

| miR-291a-3p | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Dermal Fibroblasts | TGF-β receptor 2 | Reduces cellular senescence markers, suppresses TGF-β signaling | [31] |

| miR-199a-3p | Serum (Psoriasis patients) | Skin cells | Undefined | Elevated in psoriasis, correlates with disease severity | [30] |

The mechanistic actions of these miRNAs illustrate sophisticated regulatory networks. For instance, miR-135a-mediated inhibition of LATS2 kinase leads to subsequent activation of YAP/TAZ signaling, a crucial pathway for cell proliferation and migration [31]. Similarly, miR-146a targeting of Src kinase mitigates endothelial senescence, particularly relevant in diabetic wound healing where cellular senescence is prevalent [30]. The functional specificity of these exosomal miRNAs enables precise modulation of recipient cell behavior, making them potent therapeutic candidates.

Key Exosomal Proteins and Their Functional Roles

While miRNAs provide sophisticated gene regulation, exosomal proteins often deliver immediate functional signals to recipient cells. The protein cargo includes surface receptors, enzymes, and growth factors that directly activate signaling pathways in target cells.

Table 2: Key Exosomal Proteins in Skin Repair and Recipient Cell Modulation

| Protein Cargo | Exosome Source | Target Cells | Molecular Targets/Pathways | Functional Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF | Multiple cell sources | Endothelial cells | VEGF Receptor | Promotes angiogenesis, endothelial cell proliferation and migration | [33] [9] |

| TGF-β | Mesenchymal Stem Cells | Fibroblasts, Keratinocytes | SMAD pathway | Modulates cell proliferation, differentiation, and immune regulation | [30] |

| EGF | Multiple cell sources | Keratinocytes, Fibroblasts | EGFR pathway | Promotes epithelial cell proliferation and migration | [30] |

| Wnt4 | Mesenchymal Stem Cells | Endothelial cells | β-catenin pathway | Promotes angiogenesis | [30] |

| Cytoplasmic PLA2 | Mast Cells (IFN-α treated) | T cells | CD1a lipid presentation | Generates neo-lipid antigens, induces IL-22 and IL-17A production (psoriasis) | [32] |

| Olfactomedin 4 | Neutrophils (Generalized Pustular Psoriasis) | Keratinocytes | MAPK and NF-κB pathways | Induces inflammatory gene expression (IL-36G, TNF-α, IL-1β) | [32] |

| Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81) | Virtually all exosomes | Recipient cells | Cell adhesion, fusion, and uptake | Facilitates exosome uptake by recipient cells, mediates recipient cell targeting | [30] [32] |

The synergistic action of protein and miRNA cargo within individual exosomes creates powerful combinatorial effects. For instance, exosomes may simultaneously deliver miR-21-3p to activate PI3K/Akt signaling and VEGF protein to directly stimulate VEGF receptors, producing a potent angiogenic response [30] [33]. This multi-component signaling approach enhances the efficacy and specificity of exosomal communication compared to single-factor therapies.

Experimental Protocols for Cargo Analysis and Functional Validation

Exosome Isolation and Characterization

Standardized methodologies are crucial for reproducible exosome research. The following protocols represent current best practices:

Isolation Methods:

- Differential Ultracentrifugation: Considered the gold standard, this method involves sequential centrifugation steps (300 × g for 10 min to remove cells; 2,000 × g for 20 min to remove debris; 10,000 × g for 30 min to remove larger vesicles; and 100,000 × g for 70 min to pellet exosomes) [4] [34]. A washing step with phosphate-buffered saline followed by a final 100,000 × g centrifugation for 70 minutes improves purity by removing co-isolated proteins.

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Separates exosomes from contaminating proteins based on size using porous polymer beads. Quick and suitable for large-scale applications, though potential pore clogging and exosome loss require consideration [4].

- Immunoaffinity Capture: Uses antibodies against exosomal surface markers (CD9, CD63, CD81) for high-purity isolation. Ideal for specific exosome subpopulations but may not capture all exosome varieties [4].

Characterization Techniques:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Determines exosome size distribution and concentration [4].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Visualizes exosome morphology and ultrastructure [4] [34].

- Western Blotting: Confirms presence of exosomal markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, ALIX) and absence of negative markers (calnexin, GM130) [4] [34].

- Flow Cytometry: With appropriate instrumentation, can detect and quantify exosomes based on surface markers [4].

The International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) MISEV (Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles) guidelines provide essential standardization for these procedures [34].

Cargo Profiling and Functional Validation

miRNA Profiling:

- RNA Extraction: Use commercial kits specifically validated for small RNA isolation from exosomes.

- Next-Generation Sequencing: Provides comprehensive, unbiased miRNA profiling. Bioinformatics analysis identifies differentially expressed miRNAs.

- qRT-PCR Validation: Confirm sequencing results using TaqMan assays specifically designed for miRNA quantification.

Protein Analysis:

- Mass Spectrometry: Liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) enables proteomic profiling of exosomal cargo.

- Western Blotting: Validates presence of specific proteins of interest.

- Antibody Arrays: High-throughput screening for specific protein classes (cytokines, growth factors).

Functional Validation:

- Gain/Loss-of-Function Studies: Transfer candidate miRNAs into exosomes via engineered parent cells or direct loading. Inhibit specific miRNAs using antagomiRs.

- Luciferase Reporter Assays: Validate direct miRNA-mRNA interactions by cloning putative target sequences downstream of a luciferase gene.

- In Vitro Functional Assays:

- Keratinocyte Migration Scratch Assay: Measure wound closure rates with/without exosome treatment.

- Endothelial Tube Formation Assay: Assess angiogenic potential on Matrigel.

- Macrophage Polarization: Flow cytometry analysis of M1/M2 markers (CD86, CD206) following exosome treatment.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for exosomal cargo analysis and functional validation, covering isolation to in vivo studies.

Signaling Pathways Regulated by Exosomal Cargo

Exosomal miRNAs and proteins converge on several key signaling pathways that regulate fundamental processes in skin biology. The following diagram illustrates the major pathways implicated in keratinocyte and endothelial cell modulation:

Diagram 2: Key signaling pathways in keratinocytes and endothelial cells modulated by MSC exosomal cargo.

The pathway diagram illustrates how exosomal cargo coordinates multiple processes simultaneously. For instance, while miR-135a promotes keratinocyte proliferation through Hippo pathway inhibition, miR-146a concurrently reduces endothelial senescence through Src targeting, and miR-181c dampens inflammation through NF-κB inhibition [30] [32] [31]. This multi-target approach explains the superior efficacy of exosome therapies compared to single-factor treatments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Exosome Cargo Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Total Exosome Isolation Kits (various vendors) | Rapid precipitation-based isolation from cell media or biofluids | Can co-precipitate contaminants; suitable for screening but may require validation with standard methods |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, Anti-CD9, Anti-CD81, Anti-TSG101, Anti-ALIX, Negative markers: Anti-Calnexin | Western blot confirmation of exosomal identity and purity | Essential for MISEV compliance; validate species reactivity |

| miRNA Analysis Kits | Small RNA Isolation Kits, miRNA Sequencing Kits, TaqMan MicroRNA Assays | Extraction, profiling, and validation of exosomal miRNAs | Select kits optimized for low-concentration small RNA; include spike-in controls for normalization |

| Proteomic Tools | Mass Spectrometry kits, Antibody Arrays for growth factors/cytokines | Comprehensive protein cargo profiling | Require specialized equipment; consider core facility collaboration |

| Functional Assay Kits | Endothelial Tube Formation Assay (Matrigel), Cell Migration Assay (Boyden chamber), Cell Proliferation Assays (CCK-8, EdU) | In vitro validation of exosome functional effects | Standardize exosome quantification (particle number vs. protein amount) |

| Engineering Tools | Transfection reagents (for parent cell modification), Electroporation systems (for direct loading), Click-chemistry kits for tracking | Modify exosomal cargo for gain/loss-of-function studies | Optimization critical for efficiency and maintaining exosome integrity |

| Tracking Reagents | Lipophilic dyes (DiI, DiD), Membrane dyes (PKH67, PKH26), Quantum dots | Label exosomes for uptake and biodistribution studies | Potential dye aggregation; include proper controls to distinguish membrane labeling from uptake |

This toolkit provides the foundational resources for conducting rigorous exosome cargo research. Selection should be guided by specific research questions, with particular attention to standardization across experiments to ensure reproducibility.

The sophisticated cargo of exosomes, particularly miRNAs and proteins, represents a powerful mechanism for functional modulation of recipient cells that is highly relevant to MSC exosome uptake by keratinocytes and endothelial cells. The precise targeting of key signaling pathways including PI3K/Akt, Hippo/YAP, Wnt/β-catenin, and NF-κB enables exosomes to coordinate complex processes such as re-epithelialization, angiogenesis, and inflammation resolution. As research advances, engineered exosomes with enhanced or specific cargo loading represent the next frontier in therapeutic development [33] [4]. The standardization of isolation protocols, functional assays, and analytical techniques remains crucial for translating these findings into clinical applications for wound healing, skin regeneration, and the treatment of inflammatory skin diseases.

From Observation to Application: Methodologies for Tracking and Leveraging Uptake

In the field of regenerative medicine, understanding the mechanisms by which recipient cells internalize mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) is paramount for advancing therapeutic applications. Research focusing on keratinocytes and endothelial cells—key players in skin regeneration and vascular repair—has highlighted the need for sophisticated methodological approaches to visualize and quantify exosome uptake. This technical guide details three cornerstone techniques: electron microscopy for ultrastructural analysis, PKH26/lipophilic dye labeling for membrane integration studies, and immunofluorescence for specific antigen detection. Each method offers unique insights into the dynamics of MSC exosome uptake, a process critical for mediating therapeutic effects in conditions ranging from radiation-induced skin injury to diabetic wound healing [31] [8].

Electron Microscopy for Ultrastructural Visualization

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) provides nanometer-scale resolution, enabling researchers to visualize the precise subcellular compartments involved in exosome internalization. For studying MSC exosome uptake by keratinocytes, a powerful specific technique involves combining the lipophilic dye PKH26 with diaminobenzidine (DAB) photo-oxidation [35].

Detailed Protocol: PKH26 Staining and DAB Photo-Oxidation for TEM

The following procedure allows for the correlation of fluorescence microscopy observations with high-resolution electron microscopy images.

- Cell Culture and Staining: Plate human keratinocyte cells (e.g., HaCaT cell line) or endothelial cells on glass coverslips. Upon reaching 70-80% confluence, stain the cells using the PKH26 Red Fluorescent Cell Linker Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. After staining, replace the dye-containing medium with fresh culture medium and incubate for various time points (e.g., 0 min, 30 min, 1 h, 3 h) to capture different stages of internalization [35].

- Fixation: Wash the cells with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fix with a mixture of 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 1 hour at 4°C [35].

- DAB Photo-Oxidation: Following fixation, incubate the cells with a DAB solution (2 mg/mL in 0.05 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.6) while simultaneously irradiating with two 8W Osram Blacklite 350 lamps for 2 hours at room temperature. The emission peaks of these lamps (550 and 580 nm) align with the excitation maximum of PKH26 (551 nm). This process generates free oxygen radicals that oxidize DAB, resulting in finely granular, electron-dense precipitates at the site of the dye [35].

- Post-processing and Embedding: Post-fix the samples with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 hour at room temperature. Subsequently, dehydrate the cells through a graded acetone series and embed in Epon resin [35].

- Sectioning and Imaging: Prepare thin sections (60-80 nm) using an ultramicrotome. To enhance the contrast of the osmicated samples while preserving the visibility of the DAB precipitates, stain the sections weakly with a 2.5% aqueous uranyl acetate solution for 1-2 minutes or with 2.5-5% gadolinium triacetate for 10 minutes. Observe the sections using a TEM operating at 80 kV [35].

Expected Results and Interpretation

This technique allows for the precise localization of PKH26-labeled membranes within the cell. At early time points, the electron-dense DAB reaction product is typically visible along the plasma membrane, including invaginations and small vesicles just beneath the cell surface, illustrating the initial stages of uptake. At later time points (e.g., 1-3 hours), the label is predominantly found within multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and multilamellar bodies, indicating endosomal trafficking and downstream processing [35]. The central role of MVBs in the endocytotic pathway makes them a key organelle for confirming successful exosome internalization.

Lipophilic Dye Labeling (PKH26)

Lipophilic dyes like PKH26 are widely used for tracking exosomes in live cells due to their strong fluorescence and stable integration into lipid bilayers.

Protocol: Labeling and Tracking of MSC Exosomes