Vascular Integration in 3D Bioprinting: Strategies for Connecting Engineered Tissues to the Host Circulatory System

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the strategies and challenges in achieving functional integration between bioprinted tissues and the host vasculature—a critical hurdle in regenerative medicine.

Vascular Integration in 3D Bioprinting: Strategies for Connecting Engineered Tissues to the Host Circulatory System

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the strategies and challenges in achieving functional integration between bioprinted tissues and the host vasculature—a critical hurdle in regenerative medicine. It explores the foundational biology of vascular networks, details advanced bioprinting methodologies for creating hierarchical vasculature, and addresses key optimization challenges such as immune response and structural stability. Furthermore, it evaluates current validation techniques and comparative performance of different approaches, offering researchers and drug development professionals a roadmap for advancing tissue constructs from the laboratory to clinical applications.

The Biological Blueprint: Understanding Native Vasculature and Integration Fundamentals

The Critical Role of Vascularization in Tissue Survival and Function

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is vascularization critical for 3D-bioprinted tissues? Vascularization is essential for delivering oxygen and nutrients and removing waste products. In the absence of blood perfusion, simple diffusion can only support cells within 100–200 µm from a nutrient source. Constructs larger than a few hundred microns quickly develop necrotic cores if not vascularized, which limits the engineering of thick, functional tissues [1].

2. What are the primary bioprinting methods for creating vascular networks? Several advanced bioprinting modalities enable the fabrication of vascular structures:

- Sacrificial Writing: A fugitive material is printed as a vascular template and later dissolved, leaving behind perfusable channels [1].

- Coaxial Extrusion: Uses concentric nozzles to directly print tubular, vessel-like structures in a single step [1].

- Freeform Reversible Embedding of Suspended Hydrogels (FRESH): Prints bioink within a temporary gel support bath, allowing the creation of complex, branching vessels that are held in place until cured [1].

- Rotating Mandrel Method: A scaffold-free approach where bioink is deposited onto a rotating rod to create the tubular structure of a blood vessel [2].

3. Our bioprinted constructs have low cell viability. What are the common causes? Low cell viability can stem from multiple factors related to the bioprinting process and subsequent culture conditions [3] [4]:

- Shear Stress: During extrusion-based bioprinting, cells experience shear stress from high print pressure, small nozzle diameters, or high bioink viscosity, leading to cell damage [5] [4].

- Needle Clogging: Using a bioink with particle sizes larger than the needle gauge or inhomogeneous mixing can cause clogs, requiring higher, more damaging pressures to extrude [6].

- Structural Collapse: If the bioink has insufficient viscosity or crosslinking time, 3D structures may merge or collapse, compromising internal nutrient diffusion [6].

- Contamination: A non-sterile environment during bioink preparation or printing can lead to cell death [6].

4. How can we improve integration between bioprinted vasculature and the host's blood vessels? Promising strategies focus on encouraging host vessels to infiltrate and connect with the bioprinted network. Microfluidic perfusion of bioprinted channels immediately after printing provides endothelial cells with essential shear stress cues. This promotes the formation of a stable, mature endothelium with strong cell-cell junctions and anti-thrombogenic properties, which is critical for seamless integration and long-term patency upon implantation [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Low Cell Viability in Bioprinted Constructs

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioprinting Process | High shear stress during extrusion | - Use a larger needle diameter or a tapered tip.- Optimize and reduce the print pressure.- Slow down the print speed.- Use bioinks with shear-thinning properties. | [5] [3] [6] |

| Needle clogging | - Ensure bioink homogeneity and avoid particle agglomeration.- Use a needle with a larger gauge.- For persistent clogs, dissolve residual polymer with an appropriate solvent. | [6] | |

| Bioink & Crosslinking | Lack of 3D structure; layers merge | - Increase bioink viscosity through formulation.- Optimize and increase crosslinking time for the bottom layer before printing the next. | [6] |

| Harsh crosslinking methods | - Explore alternative, gentler crosslinking mechanisms (e.g., ionic, enzymatic).- For photocrosslinking, optimize UV wavelength and exposure time. | [3] | |

| Post-Printing Culture | Necrotic core in thick constructs | - Incorporate perfusable vascular channels during the design phase.- Use dynamic culture systems (bioreactors) to provide nutrient flow. | [1] [7] |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Vascular Network Fabrication

| Problem | Possible Reason | Solution Approach | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Printed vessels lack structural integrity | Bioink lacks sufficient mechanical strength or crosslinking is inadequate. | - Use hybrid bioinks combining natural and synthetic polymers for tunable strength.- Optimize crosslinker concentration and method (ionic, UV) for stronger gels. | [1] [6] |

| Failure to form patent (open), perfusable channels | Sacrificial ink is not fully removed or channels collapse. | - Ensure the sacrificial material is completely dissolved by the removal agent.- Use a support bath (e.g., FRESH technique) to print complex channels that resist collapse. | [1] |

| Poor endothelialization of channel walls | Endothelial cells are not properly seeded or are damaged by flow. | - Line channels with endothelial cells post-printing using low, gentle flow rates.- Use coaxial bioprinting to simultaneously create the vessel wall and an endothelial lining. | [1] [7] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Creating a Functional 3D-Bioprinted Blood Vessel Using a Rotating Mandrel

This protocol is adapted from a recent study that successfully implanted a bioprinted aorta into a rat model [2].

1. Bioink Preparation:

- Cells: Use rat aortic fibroblasts (FCs) and smooth muscle cells (SMCs). Harvest cells at passage 10 or less upon reaching 80-90% confluence.

- Hydrogel: Use a commercial hydrogel kit such as HyStem-C, which contains hyaluronic acid, gelatin, and polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA).

- Formulation: Encapsulate the cells at a high density (e.g., 100 million cells/mL) in the crosslinked hydrogel mixture. One tested ratio is 70% SMCs and 30% FCs to mimic the vascular wall layers.

2. Bioprinting Process:

- Method: Employ a scaffold-free bioprinting approach using a rotating mandrel.

- Procedure: Load the prepared bioink into the bioprinter syringe. Extrude the bioink directly onto a rotating stainless-steel mandrel to form a tubular construct.

- Crosslinking: Allow the hydrogel to crosslink according to the manufacturer's specifications to achieve final mechanical integrity.

3. Maturation and Implantation:

- Maturation: Culture the printed vascular conduit in a bioreactor that provides physiological flow and pressure conditions to promote tissue maturation.

- Implantation: The bioprinted aortas were well-tolerated and well-incorporated into the native vasculature of rats, demonstrating physiological behavior.

Protocol 2: Incorporating Perfusable Vasculature using Sacrificial Writing

This method is widely used to create complex, branching vascular networks within bulk tissue constructs [1].

1. Material Selection:

- Sacrificial Ink: Select a fugitive material such as Pluronic F-127 or carbohydrate glass, which can be easily printed and later removed.

- Structural Bioink: Choose a biocompatible hydrogel like collagen, fibrin, or a GelMA blend that supports cell growth and can be crosslinked around the sacrificial template.

2. Printing Process:

- Co-printing: Use a bioprinter with multiple printheads. First, print the 3D network of the sacrificial ink.

- Embedding: Subsequently, encapsulate the entire sacrificial network within the cell-laden structural bioink and crosslink it.

3. Sacrificial Ink Removal:

- Dissolution: After crosslinking the structural hydrogel, cool the construct (for Pluronic F-127) or flush it with a specific solution (e.g., culture medium for carbohydrate glass) to liquefy and evacuate the sacrificial ink, leaving behind hollow, perfusable channels.

4. Endothelialization:

- Seeding: Introduce an endothelial cell suspension (e.g., HUVECs) into the channels and use a perfusion system to circulate the cells, allowing them to adhere and form a confluent endothelium.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Hyaluronic Acid-based Hydrogel (e.g., HyStem-C) | Provides a biocompatible, crosslinkable matrix that supports cell adhesion, motility, and proliferation. Used as a base for bioinks. | Served as the primary bioink material for creating implantable blood vessels in the rotating mandrel protocol [2]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) / PEG Diacrylate (PEGDA) | A synthetic hydrogel offering tunable mechanical properties; PEGDA is photocrosslinkable for high printing fidelity. | Used in hybrid bioinks to provide mechanical strength and in sacrificial writing for structural support [1] [2]. |

| Pluronic F-127 | A thermoreversible polymer used as a sacrificial ink. It is solid at cell culture temperatures (37°C) and liquid when cooled, allowing for easy removal. | A common fugitive material printed to create the template for vascular channels, which is later cooled and evacuated [1]. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | A photocrosslinkable derivative of gelatin; combines the bioactivity of gelatin with the mechanical controllability of synthetic polymers. | Widely used as a structural bioink in extrusion-based and light-based bioprinting for vascularized tissues [8]. |

| Endothelial Cells (e.g., HUVECs) | Used to seed the lumen of fabricated channels to form a natural, non-thrombogenic endothelial lining, crucial for vascular function and integration. | Perfused through channels created by sacrificial writing or coaxial printing to form a functional endothelium [1]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

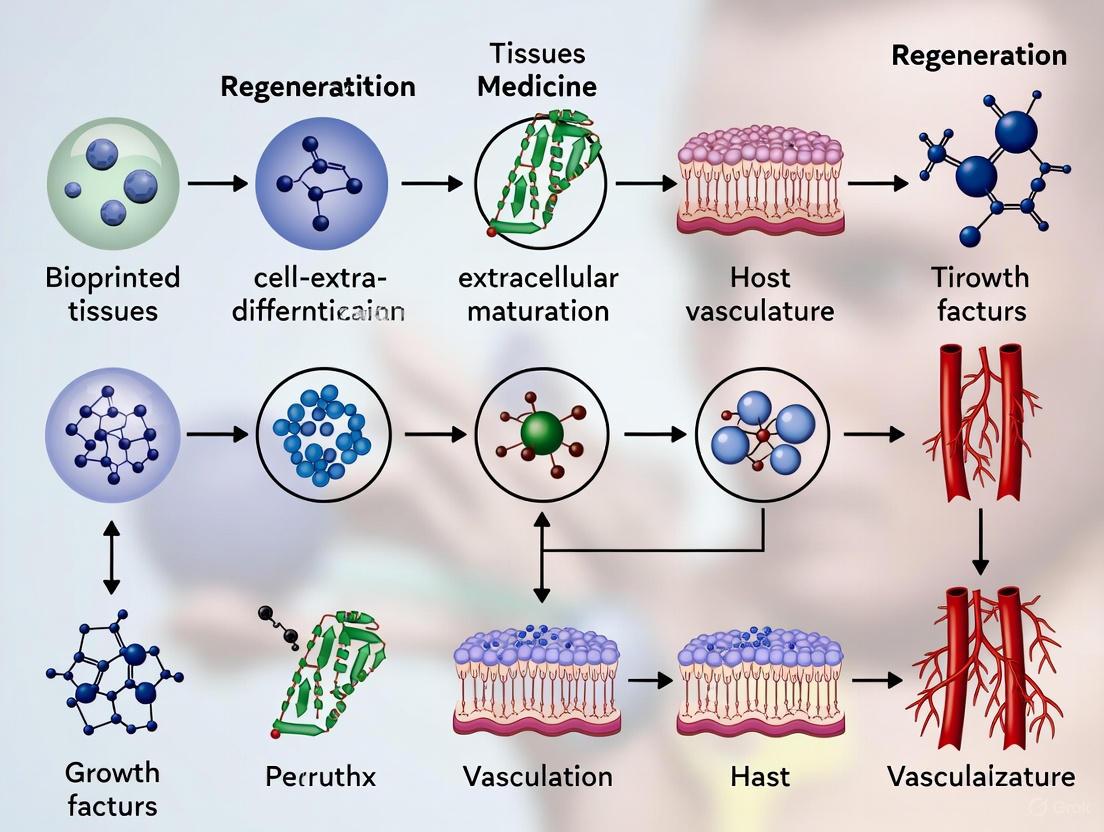

Diagram 1: Vascular Integration Pathway

Diagram 2: Bioprinted Vessel Experiment Workflow

Biological Processes of Vasculogenesis and Angiogenesis

This technical support center provides troubleshooting and methodological guidance for researchers working on the integration of bioprinted tissues with host vasculature. The successful clinical translation of engineered tissues depends on rapid and functional vascularization, a process governed by the fundamental biological mechanisms of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Vasculogenesis involves the de novo formation of blood vessels from endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) or angioblasts, which assemble into a primitive capillary plexus [9] [10]. Angiogenesis, in contrast, describes the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing ones through endothelial cell sprouting and remodeling [11] [10]. This guide addresses the specific challenges you might encounter when replicating these processes in bioprinted constructs.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

1. Our bioprinted vascular networks are regressing before they can connect with the host. What are the potential causes?

Vascular regression is often a failure of maturation and stabilization.

- Cause: Lack of pericyte or vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) recruitment [9]. Newly formed endothelial tubes are fragile and require the physical support and biochemical signaling provided by mural cells.

- Solution: Incorporate pericyte precursors or VSMCs into your bioink or co-culture system. Ensure your hydrogel supports the migration and adhesion of these cells. The secretion of factors like Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-BB (PDGF-BB) from endothelial cells is crucial for attracting mural cells [9].

2. Why are the vessels in our construct leaky and non-functional, even though they are perfusable?

The presence of a lumen does not equate to a functional barrier.

- Cause: Immature cell-cell junctions and incomplete basement membrane formation [9] [11]. Functional vessels require strong adherens junctions (dependent on VE-cadherin) and tight junctions to control permeability.

- Solution: Allow sufficient time for in vitro maturation post-printing. Apply physiological flow conditions, as shear stress is a key promoter of endothelial quiescence and barrier function [12]. Verify the expression of junctional proteins like VE-cadherin and ZO-1 in your models [9].

3. What is the "angiogenic switch" and why is it relevant to in vitro models?

The "angiogenic switch" is a critical concept for initiating angiogenesis in your constructs.

- Answer: It describes the shift in the local equilibrium from a predominance of anti-angiogenic factors to a predominance of pro-angiogenic factors [11]. This switch is often triggered by hypoxia within the tissue.

- Relevance: To induce angiogenesis in your bioprinted tissue, you must actively create conditions that flip this switch. This can be achieved by creating a hypoxic gradient or by directly supplementing with pro-angiogenic factors like VEGF [11] [10].

4. Our bioprinted capillaries lack the hierarchical structure of native vasculature. How can we better mimic nature?

Native vasculature is a multi-scale network from arteries down to capillaries.

- Cause: Many bioprinting approaches focus on a single scale, typically microvascular networks, and neglect the need for larger feeding and draining vessels [9].

- Solution: Employ a multi-strategy approach. Combine different bioprinting techniques to create hierarchical networks. For example, use extrusion bioprinting to create larger, perfusable channel designs, and leverage self-assembly or sacrificial printing to create the finer capillary networks [13] [12]. This ensures efficient perfusion from the macro- to the micro-scale.

Experimental Protocols for Key Assessments

Protocol 1: Establishing a 3D Bioprinted Co-culture Model for Angiogenesis

This protocol details a method to recapitulate branching angiogenesis using a fibroblast-endothelial cell co-culture system within a bioprinted construct [10].

- Bioink Formulation:

- 7.5% (w/v) Gelatin

- 0.5% (w/v) Alginate

- 2% (w/v) Fibrinogen

- Cell Culture:

- Endothelial Cells: Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs).

- Support Cells: Human dermal fibroblasts.

- Culture both cell types in their respective standard media before bioink preparation.

- Bioprinting and Post-Processing:

- Mix fibroblasts and HUVECs into the bioink at a defined density (e.g., 1x10^6 cells/mL each).

- Bioprint the cell-laden construct using a microextrusion bioprinter.

- After printing, crosslink the construct by immersing it in a solution containing thrombin to initiate fibrin polymerization from fibrinogen, forming a stable gel.

- Culture and Maturation:

- Maintain the bioprinted tissue in a suitable endothelial cell growth medium.

- Culture for 7-14 days, with medium changes every 2-3 days.

- The fibroblasts and HUVECs will communicate bidirectionally, leading to the self-organization of endothelial cells into tubular, branching structures within the matrix [10].

- Validation:

- Use immunohistochemistry to stain for CD31/PECAM-1 (an endothelial cell marker) to visualize the tubular networks.

- Perform proteomic analysis (e.g., multiplex ELISA) on the culture supernatant to detect the presence of key angiogenic proteins like VEGF, FGF, and PDGF.

Protocol 2: Assessing Host Integration (Inosculation)

This protocol outlines steps to evaluate the connection between pre-formed vessels in a bioprinted construct and the host vasculature after implantation.

- Pre-vascularization:

- Generate a bioprinted tissue with a defined, perfusable vascular network using HUVECs as described in Protocol 1.

- Optionally, label the endothelial cells with a fluorescent cell tracker (e.g., CM-Dil) prior to implantation for tracking.

- Implantation:

- Implant the pre-vascularized construct into an appropriate animal model (e.g., mouse dorsal skinfold chamber or subcutaneous model).

- Analysis:

- Perfusion Assessment: At various time points post-implantation, intravenously inject a fluorescently labelled lectin (e.g., FITC-Lens culinaris agglutinin) or dextran. The presence of the tracer within the lumens of the bioprinted vessels confirms functional anastomosis with the host circulatory system [9].

- Histology: Explain the construct and process for histology. Staining for host-specific (e.g., if using human cells in a mouse model) and donor-specific endothelial markers can confirm the hybrid nature of the connected vessels.

Quantitative Data and Reagents

Table 1: Key Angiogenic Growth Factors and Their Functions

| Growth Factor | Primary Receptor | Core Function in Vascularization | Key Considerations for Experiments |

|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF-A [14] [10] | VEGFR2 | Potent mitogen and chemoattractant for endothelial cells. Critical for sprouting angiogenesis. | Multiple isoforms exist (e.g., VEGF121, VEGF165) with different heparin-binding affinities and diffusion properties [14]. |

| VEGF-C [14] | VEGFR3 | Primarily drives lymphangiogenesis. In its mature form, can also activate VEGFR2. | Requires proteolytic processing (e.g., by ADAMTS3) for full activation and high-affinity receptor binding [14]. |

| PDGF-BB [9] [10] | PDGFR-β | Critical for vessel maturation and stability. Chemoattractant for pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells. | Ensures newly formed vessels are stabilized and do not regress. A key factor in co-culture systems [9]. |

| bFGF (FGF-2) [10] | FGFR | Promotes endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation. Synergizes with VEGF. | Involved in both vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. A broad-spectrum mitogen for many cell types [10]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| HUVECs | The most common endothelial cell type used for in vitro vascular model generation [10]. |

| Gelatin-Based Bioink | Provides a natural, cell-adhesive microenvironment (due to RGD sequences) that supports cell migration and network formation [10]. |

| Fibrinogen | When polymerized to fibrin, forms a provisional matrix that facilitates robust endothelial cell sprouting and tubulogenesis [10]. |

| Recombinant VEGF-A | Used to induce and stimulate angiogenic sprouting in 3D cultures. A fundamental component of most angiogenic media [14] [10]. |

| Anti-CD31 Antibody | A primary antibody for immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence to identify and visualize endothelial cells and vascular networks [10]. |

| Fluorescent Lectin (e.g., FITC-labeled) | Used for perfusion studies in vivo and in vitro to label the luminal surface of functional vessels [9]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

VEGF-VEGFR2 Signaling Pathway

Workflow for Vascular Integration Study

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

Q1: What is the fundamental role of pericytes and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) in vascular stabilization?

A1: Pericytes (in microvessels) and SMCs (in larger vessels) are mural cells that are crucial for vessel maturation and stabilization. Their physical association with the nascent endothelial cell tube terminates a period of growth factor dependence and signals the cessation of vessel growth. This interaction leads to the production of basement membrane and confers mechanical stability, preventing vessel regression. The loss of these cells is associated with pathological instability, as seen in diabetic retinopathy. [15]

Q2: During an experiment, our bioprinted vascular constructs remain unstable and regress in culture. What are the potential causes?

A2: Vessel regression often points to a failure in mural cell recruitment or function. Key factors to troubleshoot include:

- Growth Factor Imbalance: Ensure your culture medium contains adequate Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-BB (PDGF-BB), which is secreted by endothelial cells to recruit mural cell precursors. Simultaneously, verify that Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) levels are not chronically high, as this can maintain vessels in an immature, unstable state. [15]

- Insufficient Cell-Cell Contact: The stabilization process requires direct contact between endothelial and mural cells, which activates Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β). This local activation inhibits endothelial proliferation and migration while promoting pericyte/SMC differentiation. Review your bioprinting protocol to ensure the spatial arrangement allows for this critical interaction. [15]

- Biomaterial Properties: The scaffold or bioink must support the deposition of a mature basement membrane. The presence of basement membrane components (e.g., collagen IV, laminin) provides a long-term signal for vessel stabilization. [15]

Q3: Our implanted bioprinted vessels fail to integrate with the host's circulatory system. How can we promote this integration?

A3: Successful integration requires the bioprinted vessel to be both perfusable and biologically active.

- Pre-vascularization: Bioprint constructs with layered bioinks containing endothelial cells and supporting cells to form a pre-made, immature network. A recent study successfully implanted a bioprinted myocardial patch by arranging layers of muscle bioink between layers of vascular bioink, which then connected with the host's blood supply. [16]

- Use of Progenitor Cells: Consider using vascular wall-resident multipotent stem cells (VW-MPSCs). These CD44+ cells, found in the arterial adventitia, can differentiate into pericytes and SMCs. When co-implanted with endothelial cells, they contribute to new vessel maturation and coverage in vivo. [17]

- Functional Endothelium: Ensure the lumen of your bioprinted vessel is lined with a functional endothelial layer that can form connections with the host endothelium. This is critical for guiding blood flow into the new construct. [18]

Q4: What are the key signaling pathways involved in the communication between endothelial cells and mural cells?

A4: The communication is mediated by several key pathways and tools:

- PDGF-BB / PDGFR-β: Endothelial cells secrete PDGF-BB, which binds to PDGFR-β on pericytes and SMC precursors, mediating their recruitment and migration. [15]

- TGF-β Activation: Direct contact between endothelial cells and mural cells leads to the local activation of latent TGF-β. Active TGF-β then inhibits endothelial cell growth and promotes mural cell differentiation. [15]

- Angiopoietins: Angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) is associated with vessel stabilization, while Angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2) can destabilize vessels by antagonizing Ang-1. [15]

- Extracellular Vesicles (EVs): Recent research highlights EVs as a communication tool. For instance, EC-derived EVs containing miR-539 and SMC-derived EVs containing miR-582 can be transferred between cells to modulate each other's phenotypes and promote vessel coverage. [19]

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways and cellular interactions during vascular maturation.

Q5: What are the critical parameters for bioprinting a stable, layered vascular construct?

A5: Successful bioprinting requires careful optimization of both biological and engineering parameters.

- Bioink Composition: Use a hybrid bioink that provides both printability and biological cues. A common approach uses a base of gelatin (for plasticity), fibrinogen (for structure), hyaluronic acid (for cell attachment), and a crosslinker like microbial transglutaminase (mTG) for stability. [16]

- Cell Source and Density: For the vascular wall, use a combination of SMCs and fibroblasts. One protocol uses a high cell density of 100 million cells/mL, with a ratio of 70% SMCs to 30% fibroblasts to mimic the tunica media and adventitia. [2]

- Scaffold-Free Technique: To avoid long culture times and potential foreign body responses, consider scaffold-free methods using a rotating mandrel to create the tubular structure, allowing deposited cells to secrete their own extracellular matrix. [2]

- Spatial Design: For complex tissues like a myocardial patch, alternate layers of vascular bioink (containing vascular microfragments or endothelial cells) and muscle bioink (containing cardiomyocytes) to create an integrated, perfusable network. [16]

Quantitative Data and Reagents

This table summarizes key microRNAs identified in extracellular vesicle-mediated communication between endothelial and smooth muscle cells. [19]

Table 1: Functional microRNAs in Endothelial-Smooth Muscle Cell Communication

| microRNA | Primary Secreting Cell | Key Functional Role in Vascular Maturation |

|---|---|---|

| miR-539 | Endothelial Cell (EC) | Modulates SMC phenotype; promotes vessel coverage and stabilization in vivo. |

| miR-582 | Smooth Muscle Cell (SMC) | Modulates EC phenotype; cooperates with miR-539 to trigger vessel coverage. |

This table outlines critical parameters for bioprinting a functional vascular conduit, based on a recent study. [2]

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for 3D-Bioprinting a Vascular Conduit

| Parameter | Specification | Purpose/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Type | Rat venous SMCs, Rat aortic fibroblasts | Forms the tunica media and adventitia layers of the vessel wall. |

| Bioink Base | Hyaluronic acid, Gelatin, PEGDA | Provides structural support, hydration, and a crosslinkable matrix for cell adhesion. |

| Cell Density | 100 x 10^6 cells/mL | Ensures high cell density for tissue formation without prolonged culture. |

| Cell Ratio | 70% SMCs, 30% Fibroblasts | Mimics the cellular composition of the native vascular wall. |

| Fabrication Method | Rotating mandrel (scaffold-free) | Creates a tubular structure; allows cells to form their own ECM. |

| In Vivo Outcome | Well-incorporated, physiological behavior in rat model | Demonstrates functional integration with native vasculature. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Vascular Maturation and Bioprinting Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Hyaluronic Acid & Gelatin-based Bioink | Provides a biocompatible hydrogel matrix for cell encapsulation; offers tunable mechanical properties. | Used as a base bioink for printing vascular conduits and myocardial patches. [2] [16] |

| Recombinant PDGF-BB | Recruits pericytes and smooth muscle cell precursors to nascent endothelial tubes. | Added to culture media to promote mural cell coverage in in vitro vessel formation assays. [15] |

| Recombinant TGF-β1 | Stimulates differentiation of stem/progenitor cells into SMCs; promotes vessel stabilization. | Used to induce SMC marker expression in multipotent vascular stem cells in culture. [17] |

| CD44 MicroBeads | Isolates vascular wall-resident multipotent stem cells (VW-MPSCs) via magnetic sorting. | Used for the immunoselection of CD44+ VW-MPSCs from human arterial tissue. [17] |

| Gelatin Methacrylate (GelMA) | A photopolymerizable bioink; allows high-resolution printing of complex 3D structures. | Used in bioprinting protocols to create multi-layered, cell-laden constructs for tissue engineering. [20] [21] |

| Matrigel | Basement membrane extract used for in vitro angiogenesis and co-culture assays. | Used in spheroid-based in vitro assays and in vivo Matrigel plug assays to study vessel formation. [17] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolating and Differentiating Vascular Wall-Resident Stem Cells

This protocol is adapted from methods used to isolate human CD44+ multipotent stem cells from the arterial adventitia. [17]

- Tissue Acquisition: Obtain human arterial samples (e.g., internal thoracic artery) following ethical and regulatory guidelines.

- Mechanical Dissociation: Mince the vessel tissue thoroughly under a dissection microscope to remove fatty tissue.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Incubate the minced tissue in OptiMEM I medium containing 0.2% collagenase type II and 5 U/mL elastase for 30-40 minutes at 37°C.

- Cell Suspension Preparation: Pass the digested cellular suspension through a 70 µm cell strainer and wash with PBS containing 5% FCS.

- CD44+ Cell Isolation: Use anti-CD44 antibody conjugated to magnetic microbeads with MACS technology to positively select for VW-MPSCs from the cell suspension.

- Culture and Expansion: Plate the isolated CD44+ cells on standard plastic culture plates in complete MSC growth medium. Remove non-adherent cells after 24 hours.

- SMC Differentiation: To induce differentiation into SMCs, stimulate the VW-MPSCs with TGF-β1 (e.g., 5-10 ng/mL) for several days. Monitor the up-regulation of SMC markers (e.g., αSMA, calponin) via immunostaining or flow cytometry.

Protocol 2: Bioprinting a Multi-Layered Tissue Construct with Embedded Vasculature

This protocol summarizes the workflow for designing and printing a complex, multi-cellular construct, integrating principles from several sources. [2] [16] [20]

3D Model Design:

- Use CAD software (e.g., TinkerCAD) to design the construct. For a vascularized patch, create a multi-layered object.

- Export each layer as a separate .STL file (e.g., "Bottom" and "Top").

Bioink Preparation:

- Muscle Bioink: Mix a base hydrogel (e.g., gelatin, fibrinogen, hyaluronic acid, mTG) with the primary functional cells (e.g., cardiomyocytes derived from iPSCs).

- Vascular Bioink: Use the same base hydrogel but load it with vascular cells. This can be endothelial cells (e.g., HUVECs) or microvascular fragments from adipose tissue.

Slicing and Printer Setup:

- Import the .STL files into a slicing software (e.g., PrusaSlicer).

- Set printing parameters in "Expert" mode. Configure layer height (e.g., 0.2 mm), set vertical shells and solid layers to 0, and set infill density (e.g., 50%) with a rectilinear pattern.

Bioprinting Process:

- Load the respective bioinks into separate printheads.

- Print the construct using a layer-by-layer approach. For a myocardial patch, a successful strategy is to print three layers of muscle bioink alternated with two layers of vascular bioink. [16]

- Perform crosslinking as needed (e.g., UV or enzymatic, depending on the bioink).

Maturation and Implantation:

- Culture the bioprinted construct in a dynamic bioreactor system if possible, to promote preconditioning.

- For in vivo testing, implant the construct into an animal model (e.g., rat). Histological analysis after explant can assess integration, host cell infiltration, and the formation of a perfused vascular network.

The following diagram outlines the key stages of the bioprinting and integration workflow.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What defines a "functional" blood vessel in bioprinted tissue?

Answer: The definition of a "functional" blood vessel is inherently context-dependent and varies by target tissue. A vessel that suffices for nutrient delivery in a skin graft may be inadequate for cardiac tissue, which requires pulsatile flow and tight barrier regulation. Functionality is not a single endpoint but a spectrum of capabilities that must be evaluated over time. True functionality encompasses not just initial perfusability but also the vessel's ability to adapt, mature, and integrate within the host tissue environment [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Vessels are perfusable but fail to sustain tissue long-term

- Problem: Bioprinted constructs are initially perfused but develop necrotic cores or regress over time.

- Potential Cause 1: Lack of Vessel Maturation. The vasculature may not have undergone necessary stabilization steps, such as pericyte recruitment and basement membrane formation.

- Solution: Co-print or co-culture with supporting cells like pericytes or vascular smooth muscle cells. Ensure your bioink or culture conditions include key maturation signals such as PDGF-BB to recruit mural cells [9].

- Potential Cause 2: Inadequate Barrier Function. Vessels may be leaky, failing to establish proper organ-specific barrier properties.

FAQ 2: Why do my bioprinted pre-vascular networks fail to anastomose with the host vasculature after implantation?

Answer: Successful inosculation requires more than just the physical presence of endothelial channels. Failure often results from a lack of angiogenic potential, biochemical incompatibility, or insufficient mechanical stability in the implanted network [23] [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Lack of host-implant vascular connection

- Problem: After implantation, the bioprinted construct does not connect to the host's circulatory system.

- Potential Cause 1: Passive Endothelial Networks. The implanted endothelial cells are not in an activated state capable of sprouting toward or receiving sprouts from host vessels.

- Solution: Pre-condition the construct with pro-angiogenic factors (e.g., VEGF) in vitro before implantation. Consider using iPSC-derived endothelial cells with high angiogenic potential, such as those generated via ETV2 transcription factor activation [24].

- Potential Cause 2: Absence of Key Signaling Cues. The biochemical environment does not support the cross-talk between host and implant endothelial cells.

- Solution: Incorporate components into the bioink that promote angiogenic signaling. Studies show that sustained endothelial Akt signaling is critical for maintaining vascular stability and Jagged1/Notch signaling, which regulates smooth muscle cell coverage and functional integrity [22].

FAQ 3: How can I improve the structural hierarchy and stability of bioprinted vasculature?

Answer: Native vasculature is hierarchically organized, from capillaries to arteries. To replicate this, your biofabrication strategy must go beyond creating a single type of channel and incorporate methods to generate vessels of different diameters and wall compositions [9] [25].

Troubleshooting Guide: Uniform, immature capillary-like networks without hierarchy

- Problem: Bioprinting produces a network of vessels with similar, small diameters, lacking the larger arterioles/arteries needed for robust inflow and outflow.

- Potential Cause: Homogeneous Bioink and Printing Parameters. Using a single cell-laden bioink and identical printing parameters throughout the construct.

- Solution: Employ a multi-material bioprinting strategy. Use a supporting bioink to create larger, sacrificial channels that can be evacuated to create conduit vessels. Simultaneously, print a more permeable, angiogenic bioink in other regions to encourage the subsequent formation of microvascular networks [25]. Additionally, apply mechanical conditioning (e.g., cyclic strain) to promote the remodeling of certain channels into stronger, larger vessels [23].

The tables below consolidate key quantitative metrics for assessing vascular function and composition, essential for troubleshooting experimental outcomes.

Table 1: Functional Metrics for Vasculature Assessment

| Metric | Description | Target Tissues & Values | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perfused Vascular Volume | Volume of the construct that is actively perfused. | Cardiac: >45% volume [22] | MicroCT, lectin perfusion assays [22] |

| Capillary-to-Arteriole Ratio | Balance between exchange and conduit vessels. | Healthy Heart: Low ratio (e.g., ~2:1); Dysfunctional: Can be >5.5:1 [22] | Immunofluorescence (CD31, SMA) [22] |

| Barrier Function | Measure of vessel leakiness, tissue-dependent. | Continuous Capillaries (e.g., muscle): Tight barriers; Fenestrated (e.g., kidney): Permeable [9] | Dextran leakage assays, TEER measurement [9] |

| Vessel Maturation Index | Degree of pericyte/vSMC coverage. | Stable Microvessels: >70% coverage [9] | Co-staining (CD31/NG2 or SMA) [9] |

Table 2: Structural Hierarchy of Native Vasculature for Design Goals

| Vessel Type | Lumen Diameter | Key Cellular Components | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capillaries | 5 - 10 μm [9] | Endothelial cells, pericytes [9] [25] | Nutrient/waste exchange |

| Arterioles | 5 - 100 μm [9] | Endothelial cells, 1+ layers of SMCs [9] | Blood flow regulation |

| Arteries | >100 μm [22] | Endothelial cells, multiple SMC/elastic layers [9] [25] | Conduit, pressure dampening |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Vessel Functionality via Perfusion and Patency

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the volume and patency of perfused vasculature within an implanted bioprinted construct [22].

- Preparation of Tracer: Prepare a solution of fluorescently labeled lectin (e.g., FITC-Lectin) in a physiological buffer.

- Animal Perfusion: Under approved ethical guidelines, anesthetize the rodent host and surgically expose the aorta.

- Systemic Perfusion: Cannulate the aorta and perfuse the animal with the lectin solution at a physiological pressure to ensure capillary filling.

- Tissue Harvesting: Excise the implanted bioprinted construct and surrounding host tissue.

- Fixation and Imaging: Fix the tissue, section it, and image using confocal microscopy.

- Image Analysis:

- Use 3D reconstruction software to calculate the total volume of the lectin-positive (perfused) vasculature.

- Generate a vessel size distribution plot to identify the loss of larger, patent vessels, a key indicator of dysfunction [22].

Protocol 2: Generating Vascular Organoids via Transcription Factor Activation

Objective: To rapidly generate 3D vascular organoids (VOs) with co-differentiated endothelial and mural cells for high-throughput testing [24].

- Cell Line Preparation: Use engineered human iPSC lines with doxycycline (Dox)-inducible expression of the transcription factors ETV2 (for endothelial cells) and NKX3.1 (for mural cells).

- Mesoderm Induction: Differentiate iPSCs into mesoderm progenitor cells (MePCs) over 2 days using a medium containing a GSK-3β inhibitor.

- 3D Aggregation: Combine the two populations of MePCs (dox-ETV2 and dox-NKX3.1) in a defined ratio in an ultra-low attachment plate to form aggregates.

- Transcription Factor Activation: Add doxycycline to the culture medium for 48-72 hours to simultaneously induce ETV2 and NKX3.1 expression, driving co-differentiation.

- Organoid Maturation: After 5 days in total, harvest the formed VOs. For further maturation, the VOs can be embedded in an extracellular matrix (ECM) like Matrigel or a collagen-fibrin blend and cultured for an additional 1-2 weeks.

- Functional Validation: Confirm the formation of lumenized vessels with apical-basal polarity via immunostaining for CD31 and VE-Cadherin. Assess in vivo functionality by implanting VOs into models like hind limb ischemia and measuring perfusion recovery [24].

Key Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathway involved in maintaining vascular stability, a common point of failure in engineered vasculature.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Vascularized Construct Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Hyaluronic Acid / Gelatin / PEGDA Hydrogel | Bioink component providing compression strength, hydration, and cell adhesion sites. | Used as a base bioink for scaffold-free printing of vascular conduits on a rotating mandrel [2]. |

| Doxycycline-inducible ETV2/NKX3.1 iPSCs | Enables controlled, simultaneous differentiation of endothelial and mural cell lineages. | Rapid generation of uniform vascular organoids (VOs) within 5 days for therapeutic testing [24]. |

| Recombinant PDGF-BB | Key cytokine for the recruitment and attachment of pericytes to nascent endothelial tubes. | Added to culture medium to promote microvessel maturation and stabilization [9]. |

| Recombinant Jagged1 Peptide | Activates Notch signaling in adjacent cells. | Used as a therapeutic treatment to rescue vascular smooth muscle cell coverage and stability in Akt-deficient models [22]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guide

FAQ 1: What are the primary biological reasons for the failure of bioprinted constructs to integrate with the host vasculature?

Bioprinted constructs often fail to integrate due to a combination of factors related to the host's immune response and the biological immaturity of the engineered tissue.

- Foreign Body Response (FBR): The host's immune system recognizes the implant as foreign, triggering an inflammatory response. This can lead to the formation of a fibrotic capsule (glial scar in neural tissue), which isolates the construct, prevents vascular ingrowth, and causes a decline in the recording and stimulation capabilities of the interface [26].

- Inadequate Vascular Maturation: The presence of perfusable channels does not guarantee functional, long-term integration. Many bioprinted vasculatures regress, leak, or remain disorganized because they lack key maturation steps. These include the recruitment of pericytes or smooth muscle cells for stability and the development of strong endothelial cell-cell junctions to control barrier function [9].

- Mechanical Mismatch: A significant difference in stiffness between a rigid construct and soft host tissue (e.g., brain tissue at ~1–30 kPa) prevents seamless integration, causes micromotion damage, and exacerbates the FBR [26].

FAQ 2: Our bioprinted vascular networks form initial lumens but then regress. What are the potential causes and solutions?

Vessel regression is typically due to a lack of biological and mechanical stabilization signals.

- Cause: Absence of Mural Cell Recruitment. Nascent endothelial tubes require pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells for stability and long-term survival. This recruitment is mediated by signals like Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-BB (PDGF-BB) [9].

- Solution: Use Bioinks with Stromal Cues. Incorporate PDGF-BB into your hydrogel bioink and use bioinks that contain stromal cell populations (like pericyte precursors or smooth muscle cells) alongside endothelial cells to promote direct physical stabilization [9].

- Cause: Lack of Hemodynamic Cues. Without physiological flow and the associated shear stress, endothelial cells do not receive the necessary signals to mature, align, and form a stable, quiescent layer [1] [9].

- Solution: Implement Dynamic Perfusion. Integrate your bioprinted construct with a microfluidic bioreactor system immediately after printing. This provides flow-induced shear stress, which guides endothelial cell alignment and promotes the formation of a stable, non-thrombogenic endothelium [1].

FAQ 3: We observe robust vascular integration in small animal models, but the constructs fail to scale up. What are the key hurdles?

Scaling up presents challenges in ensuring uniform viability and function throughout a larger tissue volume.

- Diffusion Limits: Simple diffusion can only support cells within 100–200 µm of a nutrient source. In larger, cell-dense constructs, the core quickly becomes necrotic without an internal, perfusable vascular network [1].

- Hierarchical Network Design: A successful scalable design must replicate the body's natural vascular hierarchy. This includes large, mechanically robust vessels for inflow/outflow that branch into smaller arterioles for flow control, which in turn feed into dense capillary networks for nutrient exchange [9]. Most bioprinting approaches struggle to create this full range of scales in a single construct.

- Insufficient Architectural Resolution: While extrusion bioprinting can create larger channels (>100 µm), it often lacks the resolution to create the true capillary-level networks (<20 µm) required for efficient oxygen exchange throughout a thick tissue [1] [27]. Combining bioprinting with self-assembling microvasculature may be a necessary strategy [1].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Fibrotic encapsulation of the implant [26] | Mechanical mismatch; Strong foreign body response | Use softer, biomimetic materials (e.g., hydrogels) with an elastic modulus matching the host tissue; Functionalize surfaces with bioactive coatings (ECM proteins) to improve biocompatibility. |

| Leaky, unstable vasculature [9] | Lack of pericyte coverage; Immature endothelial junctions | Co-culture endothelial cells with pericyte precursors in the bioink; Apply sustained perfusion to mature junctions and enhance barrier function via VE-cadherin. |

| Necrotic core in thick constructs [1] | Lack of internal perfusion; Diffusion limits exceeded | Incorporate sacrificial bioinks (e.g., Pluronic F127) to create perfusable channels within the construct; Bioprint a hierarchical vascular tree prior to seeding parenchymal cells. |

| Poor host-graft anastomosis (inosculation) [9] | Lack of pro-angiogenic signals at the interface; Mismatched vessel diameters | Functionalize the construct's periphery with VEGF-loaded microparticles; Design the construct's peripheral vasculature to have channel sizes similar to the host's capillaries (~5-10 µm) to facilitate connection. |

| Low cell viability post-printing [28] | High shear stress during extrusion | Optimize bioink viscosity and printing parameters (pressure, speed); Use nozzles with larger diameters or bioinks with shear-thinning properties to reduce cell stress. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Functional Vascular Integration In Vivo

This protocol outlines a method for evaluating the success of vascular integration in an animal model, based on the deployment of a bioprinted blood vessel in rats [2].

1. Bioprinting the Vascular Conduit:

- Bioink Formulation: Prepare a hydrogel-based bioink. Example: Use the HyStem-C Kit containing hyaluronic acid, gelatin, and poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA). Encapsulate relevant cells (e.g., smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts) at a high density (e.g., 100 million cells/mL) [2].

- Fabrication Technique: Utilize a scaffold-free bioprinting approach on a rotating mandrel to create a tubular structure mimicking the native vessel's layers [2].

2. Pre-Implantation Maturation:

- Conditioning: Culture the bioprinted vessel in a bioreactor system that provides pulsatile flow and cyclic stretching to promote extracellular matrix (ECM) production and mechanical strengthening [2].

3. Surgical Implantation:

- Anastomosis: Surgically implant the bioprinted conduit into the target location (e.g., replacing a segment of the aorta) using standard vascular anastomosis techniques to connect it to the host's circulatory system [2].

4. Post-Implantation Analysis:

- Patency and Function: Monitor the implant over time using Doppler ultrasound to assess blood flow and patency. Explain the graft at predetermined endpoints for histological analysis [2].

- Histological Evaluation:

- Staining: Use Masson's Trichrome stain to visualize collagen deposition and tissue remodeling.

- Immunofluorescence: Stain for CD31 (PECAM-1) to identify host-derived endothelial cells that have migrated to form the new intima, confirming endothelialization [2].

- Assessment: Look for evidence of graft incorporation into the native tissue, absence of a significant fibrotic capsule, and the presence of physiological behavior similar to a native vessel [2].

Protocol 2: Process Control for Reproducible Bioprinting

This protocol describes a method to minimize print defects and improve the reproducibility of fabricated tissues, a critical factor for successful integration [29].

1. Setup:

- Equipment: Integrate a modular, low-cost (<$500) digital microscope onto any standard 3D bioprinter to enable layer-by-layer imaging during the printing process [29].

2. Printing and Monitoring:

- Image Acquisition: As the printer deposits each layer of bioink, the digital microscope captures high-resolution images of the nascent tissue structure in real-time [29].

3. AI-Based Image Analysis:

- Defect Detection: Feed the acquired images into an AI-based image analysis pipeline. This software rapidly compares the printed structure to the intended digital design (e.g., the CAD file) [29].

- Identification: The system automatically identifies common print defects, such as over-deposition or under-deposition of bioink, which can compromise the structural integrity and intended function of the final construct [29].

4. Parameter Optimization:

- Iteration: Use the feedback from the analysis to identify the optimal printing parameters (pressure, speed, temperature) for a given bioink material. This ensures high-fidelity fabrication and enhances inter-tissue reproducibility, which is foundational for reliable experimental outcomes and integration studies [29].

Signaling Pathways in Vascular Integration and Stability

The following diagram illustrates the key cellular and molecular interactions that determine the success or failure of vascular integration at the host-construct interface.

Key Signaling Pathways in Vascular Integration

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key materials and their functions for engineering the host-construct interface, as cited in recent literature.

| Research Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| FRESH Bioprinting (Collagen Bioink) [27] | Enables high-fidelity 3D printing of soft biological structures like microfluidic channels and vascular networks. | Creating fully biologic, collagen-based microphysiologic systems with perfusable channels down to ~100 µm diameter [27]. |

| Sacrificial Bioinks (e.g., Pluronic F127) [1] | Printed as a temporary scaffold to define the shape of hollow channels, then dissolved away post-printing. | Fabricating complex, branching vascular networks within a larger tissue construct. The dissolved fugitive material leaves behind open, perfusable lumens [1]. |

| Hydrogel Systems (Hyaluronic Acid, Gelatin, PEGDA) [2] | Provides a tunable, hydrated 3D microenvironment that supports cell encapsulation, adhesion, and proliferation. | Used as a bioink for bioprinting a functional rat aorta, providing compression strength and supporting cell motility [2]. |

| VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) [1] [9] | Key signaling protein that stimulates host angiogenic sprouting and guides endothelial tip cells. | Incorporated into hydrogel bioinks to create a chemical gradient that actively recruits host blood vessels toward the implant [9]. |

| PDGF-BB (Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-BB) [9] | Critical chemotactic signal secreted by endothelial cells to recruit pericytes and smooth muscle cells. | Added to bioinks to ensure the stabilization and maturation of nascent bioprinted vessels, preventing regression [9]. |

| Decellularized ECM (dECM) Bioinks [1] [30] | Provides a naturally derived, tissue-specific microenvironment rich in native biochemical cues. | Used to create bioinks that enhance tissue-specific cell function and maturation in bioprinted constructs [30]. |

Bioprinting Vascular Networks: From Bioinks to Functional Constructs

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting 3D Bioprinted Culture Viability

A sudden loss of cell viability is a common challenge in 3D bioprinting. This guide addresses the most frequent variables affecting viability, from general 3D culture conditions to specific bioprinting parameters [3].

General 3D Culture Variables

Before focusing on the printing process, ensure these foundational parameters are optimized.

Table 1: General 3D Culture Variables Affecting Viability

| Variable | Potential Issue | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Contamination | Low viability in 2D controls indicates issues with initial cell cultures. | Maintain a 2D control in all experiments. Follow standard cell culture contamination protocols. [3] |

| Material Contamination or Toxicity | New or contaminated bioink material affects cell health. | Use a pipetted thin film control to assess potential material-related issues. [3] |

| Cell Concentration | High density leads to hyperplasia; low density leads to low proliferation and death. | Run an encapsulation study to test varying cell concentrations for each new cell type or material. [3] |

| Crosslinking Process | Harsh chemicals or altered material properties from crosslinking harm cells. | Optimize crosslinking method and degree to minimize exposure and maintain desired material permeability. [3] |

| Sample Thickness | Thickness >0.2 mm can cause diffusion limitations, leading to central necrosis. | Adjust fabrication to create thinner films; use bioprinting to create structures with integrated microchannels for improved nutrient transport. [3] |

Bioprinted 3D Culture Variables

After optimizing general encapsulation, these printing-specific variables must be characterized.

Table 2: Bioprinting Process Variables Affecting Viability

| Variable | Potential Issue | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Needle Type | Shear stress from small or improperly shaped needles damages cells. | Test tapered tips and larger diameters. Conduct a 24-hour viability study comparing different needle types and pressures. [3] |

| Print Pressure | Increased pressure increases shear stress on encapsulated cells. | Test a variety of print pressures and create 3D printed thin-film controls to monitor effects on viability. [3] |

| Print Time | Prolonged print sessions can compromise cell viability depending on material, cell type, and temperature. | Track print session duration and determine the maximum print time for different bioink formulations. [3] |

Essential Experiment Controls

Implement these controls in all bioprinting studies to quickly pinpoint the source of viability issues [3].

- 2D Control: For each varying cell concentration, type, and ratio used in bioprinted samples.

- 3D Pipette Control: For each different material, material concentration, crosslinking process, and cell type/concentration.

- 3D Print Control: For each variable in the 3D pipette controls, plus each different pressure and needle type used.

Guide 2: Assessing Function of Bioprinted Vascular Tissue

A major challenge is that bioprinted vascular structures are often unsuitable for transplantation compared to natural blood vessels, and a complete assessment system is lacking. This guide provides a framework for evaluating bioprinted vasculature from multiple levels [31].

Cellular-Level Functional Assessment

Evaluate the basic cellular functions and phenotypes that are crucial for forming and maintaining stable vessels.

Table 3: Cellular-Level Assessment Parameters

| Assessment Category | Key Metrics & Markers | Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Endothelial Cell Phenotype & Connectivity | Expression of CD31 and Vascular Endothelial Cadherin (VE-cad). | Immunofluorescence. [32] |

| Vessel Maturity & Tight Junctions | Expression of Zonula Occludens-1 (ZO-1) and establishment of endothelial cell polarity. | Immunofluorescence. [32] |

| Thrombotic Response | von Willebrand factor immobilization and prostacyclin release upon contact with inflammatory mediators. | ELISA, Immunoassay. [32] |

| Signaling Function | Transient increase in intracellular Ca²⁺ and production of Nitrous Oxide (NO) in response to stimuli like ATP. | Calcium imaging, NO detection assays. [32] |

| Inflammatory Response | Upregulation of adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, MCAM) and increased adhesion of leukocytes/platelets with cytokine exposure. | Flow cytometry, adhesion assays. [32] |

Tissue-Level Functional Assessment

At this level, the focus shifts to the architecture and permeability of the formed vascular network.

Table 4: Tissue-Level Assessment Parameters

| Assessment Category | Key Metrics | Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Network Morphology | Number, average diameter, length, and degree of branching of engineered microvessels. | Microscopy image analysis (e.g., of CD31-stained samples). [32] |

| Network Permeability | Ability to control molecular transport; modulated by factors like aqueous two-phase emulsion in the bioresin. | Permeability assays, tracer diffusion studies. [33] |

| Perfusion Capability | The ability to sustain flow through the printed channels without leakage or blockage. | Perfusion assays with colored dyes or fluorescent beads. [32] |

Organ-Level Functional Application

Bioprinted vascular models can be used to simulate pathological processes and conduct drug screening at the organ level, as in vessel-on-a-chip devices [31].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary vascularization challenge in bioprinting larger tissues? The primary challenge is the lack of an efficient and extensive network of microvessels to deliver oxygen and nutrients and remove waste. Most living cells must be within 100-200 μm of a capillary to survive, making vascularization essential for engineering functional tissues of substantial size [32] [25].

Q2: What are the two main biological mechanisms for blood vessel formation that in vitro strategies aim to mimic? In vitro strategies primarily aim to mimic vasculogenesis (the de novo formation of blood vessels from endothelial progenitor cells) and angiogenesis (the sprouting of new vessels from existing ones) [32].

Q3: What are the two overarching strategies for incorporating vasculature into bioprinted constructs? The two main strategies are:

- Angiogenic Induction: Using the controlled release of angiogenic factors (e.g., VEGF, BFGF) to induce the growth of blood vessels within the printed tissue [25].

- Direct Printing: The direct printing of vascular scaffolds or channels, which can be seeded with endothelial cells to create a pre-formed vascular network [32] [25].

Q4: How can I improve the resolution and complexity of printed microchannels in hydrogel constructs? Lithographic biofabrication techniques, such as Digital Light Processing (DLP), offer superior resolution compared to conventional extrusion methods. Using specialized bioresins, this method can create high-resolution hydrogel constructs with embedded, convoluted networks of vessel-mimetic channels, including complex out-of-plane branches that are difficult to achieve with extrusion [33].

Q5: Are there rapid printing methods for creating sophisticated vascular structures? Yes, Volumetric Additive Manufacturing (VAM) is an emerging technology that enables rapid photopolymerization of entire 3D constructs in seconds to minutes, rather than layer-by-layer. This method has been used with pristine silk-based bioinks to create sophisticated, perfusable shapes and channel networks quickly [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 6: Key Reagents for Vascularized Bioprinting Experiments

| Reagent | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Gelatin-Based Bioresins | A versatile biomaterial for creating hydrogels. Ichthyic-origin gelatin can offer thermal stability at room temperature, which is ideal for lithographic printing. Can be modified with norbornene or methacryloyl groups for photochemical crosslinking. [33] |

| Silk Fibroin (SF) Bioink | A natural protein biomaterial known for its biocompatibility, tunable mechanical properties, and controllable degradability. Can be volumetrically printed in its pristine, unmodified form to create constructs with mechanical performance ranging from a few hundred Pa to hundreds of MPa. [34] |

| Silk Sericin (SS) Bioink | A silk protein often discarded as waste, but possesses valuable properties like hydrophilicity, anti-oxidation, and anti-inflammation. Can be used in its pure form for volumetric printing to create constructs with unique shape-memory properties. [34] |

| Photoinitiator System: Ru/SPS | A cytocompatible, visible-light photoinitiator system based on Tris-bipyridyl-ruthenium (II) hexahydrate (Ru) and Sodium Persulfate (SPS). Essential for crosslinking pristine silk and other bioresins under visible light in VAM and DLP printing. [34] |

| Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) | A key pro-angiogenic growth factor used to induce the formation and sprouting of blood microvessels within engineered constructs. [32] |

| Endothelial Cells (ECs) | Primary cells used to seed printed vascular channels or incorporated into bioinks to form the inner lining of microvessels, facilitating the formation of perfusable, biologically active networks. Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) are a common model. [32] |

| New Coccine | A cytocompatible photoabsorber used in lithographic printing to achieve high-resolution printing by confining the crosslinking reaction to precise locations, improving print fidelity. [33] |

Experimental Workflow: Volumetric Bioprinting of Silk-Based Vascular Constructs

The following protocol details the methodology for rapid fabrication of complex channel-laden constructs using Volumetric Additive Manufacturing (VAM), based on recent research with pristine silk bioinks [34].

Detailed Protocol:

Bioink Preparation:

- Silk Fibroin (SF) Solution: Prepare aqueous silk fibroin solution from Bombyx mori silkworm cocoons using standard lithium bromide dissolution and dialysis methods. Concentrations between 2.5% to 10% (w/v) are typically optimal for VAM, offering a good balance of printability and shape fidelity [34].

- Silk Sericin (SS) Solution: Extract silk sericin from silkworm cocoons. A concentration of 2.5% (w/v) has been identified as a key working concentration for VAM, enabling shorter crosslinking times and better shape fidelity compared to higher concentrations [34].

Photoinitiator Addition:

- To the silk bioink, add the visible-light photoinitiator system. The typical recommended concentrations are:

- Mix the bioink thoroughly but gently to avoid introducing air bubbles.

Volumetric Printing Process:

- Transfer the bioink to a transparent cylindrical vial.

- Place the vial in the VAM printer, which will rotate it continuously.

- The printer projects computed light patterns (wavelength ~525 nm) onto the rotating vial. The light patterns are calculated using a Radon transform of the target 3D model (e.g., a channel-in-cube or a brain-like structure) [34].

- The entire object is solidified via photopolymerization in a single, rapid step (typically 60-180 seconds), without the need for layer-by-layer deposition [34].

Post-Fabrication Processing:

- After printing, carefully extract the construct from the vial.

- Rinse thoroughly with sterile water or PBS to remove uncrosslinked material and photoinitiator residues.

- For SF constructs, post-processing can include ethanol treatments or mechanical loading to tune the mechanical properties and induce beta-sheet formation for stability in aqueous environments [34].

- For SS constructs, the unique reversible expansion and shrinkage (shape-memory) properties can be explored through hydration/dehydration cycles [34].

Construct Characterization:

- Viability: Culture with human mesenchymal stromal cells or other relevant cell types to assess cytocompatibility over extended periods (e.g., 1 month) [34].

- Functionality: Perform perfusion assays to validate the functionality of the embedded channels. Characterize the mechanical properties via rheometry or uniaxial compression/tensile testing [34].

Extrusion-Based Bioprinting for Macroscale Vascular Conduits

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

This section addresses common technical challenges encountered during the extrusion-based bioprinting of macroscale vascular conduits, providing targeted solutions to ensure print fidelity, cell viability, and structural integrity.

FAQ 1: How do I prevent needle tip collisions with the print bed?

- Problem: The extruder needle crashes into the print bed when moving to the start position.

- Solution: This is typically a G-code calibration issue. Ensure the center point coordinates of your print area are accurately set. For specific printers, use commands like

G1 Z5 F200(for Trivima printers) to adjust the Z-axis height before extruder head movement, moving the bed down or head up by 5mm to avoid collision [6].

FAQ 2: What causes air bubbles in the bioink, and how can I remove them?

- Problem: Air bubbles in the bioink lead to inhomogeneity, voids, and uneven printing [6].

- Solution:

FAQ 3: My scaffold lacks structural integrity and layers merge or collapse.

- Problem: Printed layers fail to stack into a 3D structure, resulting in a collapsed 2D-like appearance.

- Solution:

- Bioink Viscosity: Perform rheological tests to ensure your bioink has sufficient thixotropic (shear-thinning) properties for extrusion and rapid structural recovery post-deposition [6].

- Crosslinking Optimization: Optimize the crosslinking method and time to ensure the bottom layer stabilizes quickly enough to support subsequent layers. This is critical for layer stacking [6].

FAQ 4: Why does my needle keep clogging during printing?

- Problem: Intermittent or complete cessation of bioink extrusion.

- Solution:

- Ensure Homogeneity: Confirm the bioink is homogeneous without phase separation [6].

- Adjust Pressure: Gradually increase extrusion pressure. If working with cells, limit pressure to a maximum of 2 bar to preserve viability. If clogging persists, change to a larger needle gauge [6].

- Particle Size Check: If using nanoparticles, ensure their size is smaller than the needle gauge diameter to prevent physical clogging. Pre-characterize particle size and ensure they do not agglomerate in the bioink [6].

FAQ 5: How can I maintain cell viability and prevent contamination during long-term incubation?

- Problem: Printed constructs show contamination or low cell viability after incubation.

- Solution:

- Sterile Environment: Maintain a sterile environment using biosafety cabinets. Use printers with inbuilt Germicidal UV and HEPA filters if available. Sterilize the print bed with 70% ethanol before printing [6].

- Material Sterilization: Ensure all biomaterials and media are sterilized (via autoclave, UV, or gamma irradiation) before being mixed with cells to prepare bioink [6].

Key Experimental Protocols for Vascular Conduit Bioprinting

This section outlines a detailed methodology for fabricating a scaffold-free, cell-laden macroscale vascular conduit, adapted from a recent study [2]. The protocol emphasizes the creation of a functional vessel without synthetic scaffolds, leveraging a rotating mandrel for structural support.

Protocol: Scaffold-Free Bioprinting of a Vascular Conduit Using a Rotating Mandrel

Objective: To fabricate a tri-layered, cellular vascular conduit suitable for in vivo implantation and integration studies.

Materials and Reagents:

- Cells: Rat aortic smooth muscle cells (SMCs) and rat fibroblasts (FCs). Use cells at passage 10 or less [2].

- Bioink Kit: HyStem-C Kit (or equivalent), containing Hyaluronic Acid, Gelatin, and Polyethylene Glycol Diacrylate (PEGDA) [2].

- Bioprinter: An extrusion-based bioprinter (e.g., Organovo) capable of precise temperature and pressure control.

- Hardware: A sterile, rotating stainless-steel mandrel (diameter tailored to the desired vessel size).

- Cell Culture Media: Standard media appropriate for the chosen SMCs and FCs.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Bioink Preparation: a. Culture and expand rat SMCs and FCs separately until 80-90% confluence is achieved [2]. b. Harvest the cells and create two distinct bioink mixtures according to the hydrogel kit instructions: * Mixture 1 (Tunica Media Mimic): 70% SMCs and 30% FCs, encapsulated at a final cell density of 100 x 10^6 cells/mL in the crosslinked hydrogel [2]. * Mixture 2 (Tunica Adventitia Mimic): 100% FCs, encapsulated at the same high cell density [2]. c. Keep the bioinks on ice or in cooled printer cartridges to prevent premature crosslinking.

Mandrel and Printer Setup: a. Sterilize the stainless-steel mandrel and mount it onto the rotating axis within the bioprinter's sterile environment. b. Calibrate the printer's extruder path to align with the rotating mandrel, ensuring a consistent stand-off distance between the nozzle and the mandrel surface. c. Set the printing temperature to maintain the bioink's viscosity for optimal extrusion, typically between 4-10°C.

Bioprinting Process: a. Load the SMC/FC bioink (Mixture 1) into the printer cartridge. b. Initiate mandrel rotation and extrude the bioink in a continuous, helical pattern along the length of the rotating mandrel to form the inner layer of the conduit. c. After completing the first layer, switch to the FC bioink (Mixture 2). d. Extrude the second layer directly over the first, creating an outer fibroblast-rich layer. This two-layer structure mimics the tunica media and adventitia of a native blood vessel [2]. e. Key printing parameters to optimize include: * Extrusion Pressure: Adjust to achieve a consistent filament without straining cells. * Print Speed: Synchronize with mandrel rotation speed for uniform deposition. * Nozzle Gauge: Select based on the desired wall thickness and to minimize cell shear stress.

Post-Printing Crosslinking & Maturation: a. Following deposition, the PEGDA-based hydrogel is crosslinked, typically via exposure to UV light or a chemical initiator as per the kit's protocol, to solidify the structure [2]. b. Transfer the mandrel with the printed conduit to a bioreactor or culture vessel. c. Culture the construct under dynamic flow conditions if possible, using specific culture media to promote tissue maturation and ECM production over several days [2].

Pre-Implantation Processing: a. After the maturation period, carefully remove the solidified vascular conduit from the mandrel. b. The conduit is now ready for in vivo implantation studies. The inner lumen is not pre-seeded with endothelial cells in this protocol, relying on in vivo self-endothelialization by host progenitor cells after implantation [2].

Key Parameters for Successful Conduit Fabrication

Table 1: Critical Parameters for Scaffold-Free Vascular Conduit Bioprinting [2]

| Parameter | Specification | Function/Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Density | 100 x 10^6 cells/mL | Provides high cell-cell interaction for scaffold-free integrity and ECM production. |

| Cell Ratio (Inner Layer) | 70% SMC / 30% FC | Recapitulates the cellular composition of the native tunica media. |

| Bioink Composition | Hyaluronic Acid, Gelatin, PEGDA | Provides a temporary, cell-supportive hydrogel matrix with tunable mechanical properties. |

| Structural Support | Rotating Steel Mandrel | Acts as a scaffold-free template for the tubular conduit shape during printing. |

| Endothelialization | Not pre-seeded | Relies on host-mediated endothelialization post-implantation for intima formation. |

Visualization of Workflows and Signaling

Vascular Conduit Bioprinting and Host Integration Workflow

This diagram outlines the complete experimental journey from bioink preparation to the assessment of host integration, highlighting key steps and checkpoints.

Title: Vascular Conduit Bioprinting and Integration Workflow

Key Signaling Pathways in Host Graft Integration

Successful integration of bioprinted vascular conduits relies on critical biological signaling pathways that drive host cell recruitment and vessel remodeling. This diagram maps the primary pathways involved.

Title: Key Signaling for Host Vascular Integration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table catalogs the core materials and reagents essential for the experimental bioprinting of macroscale vascular conduits, as derived from the featured protocol and related literature.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Vascular Conduit Bioprinting [35] [1] [2]

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Protocol | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Smooth Muscle Cells (SMCs) | Primary cellular component for the tunica media layer; provides contractile function and ECM production. | Rat aortic SMCs [2]. Critical for mechanical strength and vasoactivity. |

| Fibroblasts (FCs) | Primary cellular component for the tunica adventitia; provides structural support and secretes collagen. | Rat aortic fibroblasts [2]. |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | A core component of the bioink hydrogel; provides hydration, compression strength, and supports cell motility. | Part of HyStem-C Kit [2]. Mimics the native extracellular matrix. |

| Gelatin | A core component of the bioink hydrogel; provides cell adhesion motifs (e.g., RGD sequences) for cell attachment and proliferation. | Part of HyStem-C Kit [2]. Often derived from denatured collagen. |

| PEGDA (Polyethylene Glycol Diacrylate) | A synthetic polymer used as a crosslinker in the bioink; provides tunable mechanical properties and stabilizes the printed structure. | Part of HyStem-C Kit [2]. Crosslinks via UV light or chemical initiators. |

| Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) | A key growth factor used in many vascularization strategies to promote endothelial cell migration, proliferation, and vessel formation. | Often added to bioink or culture media [35] [25]. Critical for guiding host vasculature integration. |

| Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF) | A growth factor that stimulates the proliferation of various cell types, including endothelial cells and SMCs, supporting vessel maturation. | Used as an additive in culture [35]. |

| Decellularized ECM (dECM) | A natural biomaterial derived from decellularized tissues; used as a bioink component to provide a tissue-specific microenvironment. | Can be derived from various tissues to enhance biological function [1] [30]. |

Scaffold-free bioprinting represents a paradigm shift in tissue engineering, moving away from exogenous biomaterial scaffolds toward systems that rely on cellular self-assembly to create functional tissues. Within cardiovascular medicine and the broader challenge of integrating bioprinted tissues with host vasculature, these approaches offer significant advantages, including high cell density, minimized foreign body response, and the capacity for cells to produce and organize their own native extracellular matrix (ECM) [36]. The absence of artificial scaffolds eliminates concerns about scaffold degradation rates, potential inflammatory responses, and interference with direct cell-cell communication, which are crucial for forming functional vascular networks [2] [37]. This technical support center focuses on two prominent scaffold-free techniques—the Kenzan Method and Rotating Mandrel Techniques—providing researchers with detailed protocols, troubleshooting guides, and resources to advance their work in vascularized tissue engineering.

Core Principles and Methodologies

The Kenzan Method

The Kenzan method is a robotic bioprinting technology that utilizes a microneedle array to hold and position cellular spheroids as building blocks for tissue construction without the use of hydrogel-based bioinks or scaffolds [38] [39].

- Fundamental Principle: Pre-formed, self-assembled cell spheroids are impaled onto a fine array of stainless-steel microneedles (the "Kenzan," Japanese for "sword array") by a robotic arm. The system positions the spheroids in a predefined 3D pattern, and through subsequent fusion processes, the spheroids coalesce into a single, cohesive tissue construct [38] [39]. The microneedles are removed after the tissue has fused sufficiently to become self-supporting.

- Key Experimental Protocol: The following workflow is adapted from established practices for creating tubular structures like vascular grafts or cardiac patches [39] [40]:

- Spheroid Preparation: Cells (e.g., fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, or cardiomyocytes) are aggregated into spheroids of a highly uniform diameter, typically in the range of 100-500 µm, using techniques such as hanging drop or gyratory shaking.

- Robotic Assembly: The spheroids are transferred to a bioprinter (e.g., the Regenova system by Cyfuse Biomedical). Using computer-aided design (CAD) models, the robotic arm sequentially picks up individual spheroids and impales them onto the microneedles of the Kenzan array to form the desired tubular or patch geometry.

- Maturation and Fusion: The assembled construct is transferred to a bioreactor, which provides culture medium and, for contractile tissues like cardiac patches, may provide electrical or mechanical stimulation. Over several days, the spheroids fuse into a continuous tissue, secreting their own ECM.

- Kenzan Removal: Once the construct has gained sufficient mechanical integrity from ECM deposition and tissue remodeling, the entire Kenzan array is carefully removed, leaving a scaffold-free tissue.

Rotating Mandrel Techniques